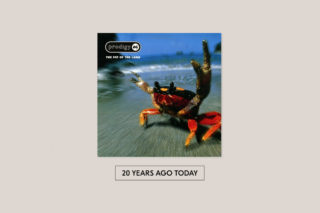

We were so busy being scared by The Prodigy’s ‘The Fat of The Land’ that nobody noticed how utterly corny it was

It's 20 years old today

It's 20 years old today

In the summer of 1997, ‘Never Mind The Bollocks’ (perhaps the first album to induce widespread moral panic in the UK) was almost exactly as old as ‘The Fat Of The Land’ (perhaps the last) is today. Those intervening twenty years, however, during which Frankie Goes To Hollywood, acid house and riot grrrl had irked middle England, had somewhat dulled the spectacle of pop controversy so that by the time the Prodigy reincarnated themselves as a post-rave Pistols, shock pop had acquired a sort of numb familiarity. Two decades on from the original punk menace, from Nazi flirtations and “ban this sick filth” tabloid outrage, everyone knew their role: musicians presented the taboo, the press were simultaneously appalled and fascinated, and the general public cavorted in either disgust or glee, according to taste.

That’s not to say the controversy that greeted ‘The Fat Of The Land’ was any less vivid at the time. Indeed, starting with a nakedly aggressive comeback single, progressing through an invocation of Joseph Goebbels and peaking with the release of ‘Smack My Bitch Up’’s baiting video, the Prodigy played their part for two years with Oscar-winning zeal, and the supporting cast of press and public duly followed. Nonetheless, it’s difficult to revisit the band’s imperial phase today without observing a pantomime where once lay the Sex Pistols’ high drama: while some of Keith Flint’s remarkable Johnny Rotten impressions on ‘The Fat Of The Land’ still stand up, the album at the centre of their domination has none of the same scorched-earth, year-zero feel. Instead, at twenty years distance, ‘The Fat Of The Land’ presents a very Britpopped version of hysteria, full of gesture and homage, and rather lacking in original substance.

And, just as with more conventional Britpop, when that template works, it’s irresistible. Even now, with all novelty subsided, it’s hard to deny the glistening claustrophobia of both ‘Firestarter’ and ‘Breathe’, leering twin pieces of chaos and snarl that remain heart-quickeningly antagonistic. ‘Smack My Bitch Up’, too, is a masterpiece of sampling, all pogoing elasticity and bludgeoning sub-bass, only ruined by a fairly indefensible vocal hook: Liam Howlett’s protestations about what “smack my bitch up” actually meant in the context of the Ultramagnetic MCs’ original are somewhat moot once he knowingly deleted said context.

Elsewhere, though, ‘The Fat Of The Land’ alternates between the listless and the corny, leaving it feeling bloated and strangely indistinct for a band with such a striking visual aesthetic. The burbling acid lines of ‘Funky Shit’, ‘Mindfields’ and ‘Climbatize’ hint at where The Prodigy’s third album was headed before Howlett stumbled upon Flint’s vocal charisma, and the heft of ‘Diesel Power’ is compelling even if the composition itself is underevolved. The two shots at more straight-up punk, ‘Serial Thrilla’ and a phoned-in cover of L7’s ‘Fuel My Fire’, however, are tacky appropriations in which Flint ends up evoking nothing more demonic than Krusty the Klown, and the less said about centerpiece ‘Narayan’ – nine minutes of faux-mystic bunk featuring Crispian Mills of Kula Shaker – the better.

Those missteps are a shame: moments are dotted around ‘The Fat Of The Land’ of genuine shock, invention, thrill and ingenuity, but it all adds up to the sound of Howlett losing his way, surrendering focus in order to bolster his band’s febrile reputation and to ponder what to do now that his “faceless” dance music was helmed by one of the country’s most recognisable men.

With all that in mind, then, it’s disconcerting, to be reminded of the colossal global popularity of ‘The Fat Of The Land’. Most impressively, it topped the Billboard 200 in America (for context, a feat that Oasis never achieved, and which would elude Radiohead until ‘Kid A’ in late 2000), and it also went to number one in eleven other countries. That’s disconcerting not just because of how patchy the album sounds today, but also because that level of success normally spawns copycats, which, from one angle, ‘The Fat Of The Land’ appears not to have done: the blueprint of a cartoonish punk fronting a big-beat act remains theirs alone.

That said, from another angle, ‘The Fat Of The Land’’s musical legacy is far reaching, and rather more insidious too. One of the album’s most distinctive production trademarks is the meatiness of its downbeats, which rendered its tracks as lurching, lopsided monsters apt for a sort of hypermasculine bodyslamming (as demonstrated so often by Flint in the band’s promos). Couple that with the group’s newfound heavy metal stylings, all distorted guitars and throbbing intensity, and a proto-EDM starts to form: in hindsight, one can draw a reasonably straight line between much of ‘The Fat Of the Land’ and the aggressively macho, steroidal fratboy wub that Skrillex and Deadmau5 would use to conquer American stadiums 15 years later.

Sadly, impotently furious brostep is probably not how Howlett – inveterate crate-digger, hip-hop nerd and home counties raver – envisaged being remembered, especially given the subsequent affection paid to contemporaries such as the Chemical Brothers and Daft Punk. But maybe that’s the price one pays for wilfully courting controversy, for being (for a short time at least) a threat to the nation’s youth. “We’re everyone’s dark side,” Flint told Q in 1997, proudly playing his part in the panto, and the magazine, playing theirs, emblazoned the quote on their front cover while picturing the band encased in superimposed flames. Today, that cover is as naff as it sounds. Funny how twenty years can take the sting out of almost anything.

To read all the other entries in Sam’s Twenty Years Ago Today blog, click here.