Bishop Nehru is in love with the Golden Age of hip-hop

Is discussion about rap over afternoon tea

Is discussion about rap over afternoon tea

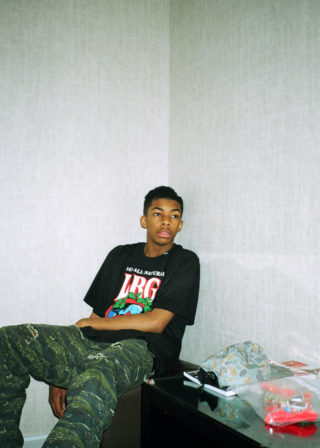

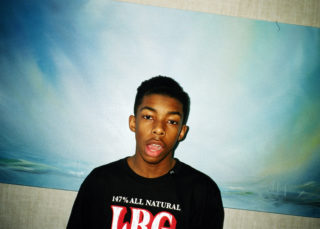

Two months ago Rockland County rapper Bishop Nehru stopped going to school. He was 16, still is. ‘Dropped out’ is too strong a term, and wholly inaccurate – Nehru switched to home tutoring so he could make time for studies and music and days like today.

In a few hours the boy from Upstate New York will perform his first show outside of the US, at London’s 100 Club at the behest of co-headliners and Nehru heroes MF Doom and Ghostface Killah. It’s pretty big deal for a kid who’s released one mixtape and has never left the States until 8pm last night.

We meet at Soho Hotel for the proud English tradition of afternoon tea – me, Bishop, his press officer, manager and father. Of course he’s chaperoned, yet I half expect him to arrive alone. The ‘Nehruvia’ mixtape has an affect of skewing how old he actually is – 13 tracks of mellow, story-telling hip-hop that harks back to the Golden Age of beats and rhymes, wisely told and deftly put together. In turn the tracks feature beats from Doom, J Dilla, Madlib and DJ Premier, and humid jazz samples – pianos, clarinets and warm brass that conjures images of kids playing double-dutch on a hot city night. There’s more of De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest about Bishop Nehru than peers A$AP Rocky, Lil B and Tyler, The Creator. He’s the antidote to the shock and awe of Odd Future, in fact, rarely cursing, pro school, laidback yet decidedly un-sleazy. He’s a good kid and makes no bones about it. “The older records sound so much more complex,” he says. “I would rather sound intelligent than ignorant. In hip-hop now it’s cool to be dumb, but I don’t think that’s cool at all.

“To me, curses are emphasizers. Let’s say you call someone a bitch, if you put ‘fucking’ in front of it, it emphasizes it, but I don’t know why rappers cuss so much. It’s ignorant, but people like it, and that’s even more odd to me. To me, people are just trying to sound tough, which is why people in hip-hop say ‘fag’, because they see calling someone else feminine in some way makes them less feminine and more of a man.”

Nehru’s other concern with where rap has been heading is the genre’s thirst for image over content. He says that’s why he respects Doom so much, “because he just makes music”, even if Doom’s iron gladiator mask does attract more attention than it deflects. Regardless, it’s a spoken word passage from Doom that gets ‘Nehruvia’ going, explaining the concept of the mask as a way to get hip-hop back to being about the music. “Hip-hop has gone in a direction where it’s almost damn near 100% on everything besides the music,” says Doom. ‘The Music’ goes on to insist how it’s about “the way you spit and how the beats roll”. Nehru then drops his flow, reminiscent in most recent years of Lupe Fiasco, again sounding older than the young man sipping English breakfast blend from a teaspoon in front of me.

Bishop’s age is what it is – impossible to ignore, but not what makes him a gifted rapper. You wouldn’t know he was still in school until you see a photo of him or meet him in person. Face to face he’s refreshingly ok with being a borderline adult. He never takes off his backpack as we sit down, for example, as if we’re hanging out at the back of a bus. He got into Little Bow Wow before anyone else, shortly followed by Pharrell and Gwen Stefani’s almost hit ‘Can I Get It Like That’ and Nas’ 2002 single ‘One Mic’. That these are songs rather than albums perhaps points to Nehru’s generation most of all.

The best movie, according to Nehru, is Superbad, with Pineapple Express a close second. Suitably, his favourite actors are Will Smith, Martin Lawrence, Jonah Hill and Seth Rogen. “I want to get into acting,” he says, the man who took his name from Tupac Shakur’s character in 2002 crime drama Juice. (Nehru also styles his hair to replicate that of the role’s). “The first thing I want to do is be the bad guy, the villain. Orrrr, it would have to be comedy and I’d be one of the funny bad guys.”

After we finish our tea, Bishop’s father and manager will rib him about the recent rebranding of his crew back home, who used to go by the name Prime Society but now operate under The Suburban Showguns. We take a group vote and all but Nehru agree that the old name was better. Papa Nehru challenges his son to include Suburban Showguns in a freestyle, which Bishop does over the table of jam and scones. He then lets out a rasping “Aaaaahhhh!” of success, much to the amusement of his father and manager. Had he been just a few years older, chances are we wouldn’t have knocked his decision at all.

“It’s my age that’s got me where I am,” he admits, “but it’s bad because you don’t want to be compared only to other 16-year-olds, but to everyone else as well. I don’t want people to say, ‘because he’s only 16, he’s number 2,’ I want them to say, ‘because he’s a rapper that’s good he’s number 2 – he deserves it’.”

Nehru is often compared to Joey Bada$$, another teen rallying against obnoxious brat-rap in favour for a back-in-the-day, vintage hip-hop sound. Bada$$ currently has the lead on Nehru, by a year in age and more than that in blog frenzy, but if you like one you’ll definitely like the other; it’s just rotten timing for Bishop, who probably thought he was the only kid making these mellow tunes against the tide created by ‘Yonkers’ and the obscene likes of Azealia Banks.

Bada$$ – now two mixtapes in with a debut album ready to go – no doubt benefits from his Flatbush, Brooklyn, neighbourhood, but Nehru is happy Upstate. He has no interest in dressing up Rockland County as the badlands it isn’t, or as the affluent area it’s not. His hometown is, “not bad, but not good”, simply ok, something that you rarely hear from young rappers who’ve learned that the Project is not where you want to be but it’s definitely where you want to be from. Bishop Nehru is a bit too honest for all that, because it’s honesty that he takes most seriously of all. “Tyler, The Creator has the career I’d like,” he tells me. “He looks like he has a lot of fun, but he seems a bit depressed about people approaching him a lot, so that’s not so good. He’s the only one that’s himself, though, and that’s key, to stay yourself.”

Nehru manages this by staying in school, even when he’s flying across the world to support Doom and Ghostface Killer, by rejecting stereotype and, he says, by making music his personal shrink. “When I make a track, first I think of anything that has affected me, so it can’t hurt me anymore. Music is therapy. So I find something that is reoccurring in my mind and I expose it, because once something is exposed you can only heal after that. That’s my basic approach. I then make a beat, and that’s basically the Band Aid, which is going to help it heal, and after that the video would be… the scab,” he says after a pause. “Everything’s good, it’s all glued together.”