When the classical world passed on serpentwithfeet he built a whole new one for himself

The fermentation of Josiah Wise

The fermentation of Josiah Wise

Bury anything deep enough and it will change. The weight of the earth creates so much pressure that transformation is inevitable. With enough time, a buried thing becomes something completely distinct from what it was. Often, people regard this process with discomfort or, worse, disgust. It makes them think of death and decomposition, of bodies turning into bones. At first glance, to bury something is to leave it behind.

Take a closer look, though, and you’ll see that buried things come back more often than not. Bones fossilise, seeds grow. For centuries, cultures around the globe have buried food underground for weeks, even months, then dug it up and eaten its fermented form. Put something in the soil, give it time, and there’s a good chance it will return to you better, and stranger.

Josiah Wise, who records under the moniker serpentwithfeet, has been thinking about this a lot in the past year. Reflecting on his new album in the Fort Greene neighbourhood of Brooklyn, he takes a long pause, reflects, and says, “It’s so beautiful to me to think about fermentation.” He means this quite literally. Over the course of our conversation, he frequently reminds me, “You got to get your probiotics!” But he means it on a much deeper level as well; fermentation, the process by which sugar is gradually converted into acid, is at the root of his new, debut album ‘soil’. The record is a testament to how giving things time to ferment is good for your art, good for body, good for your soul.

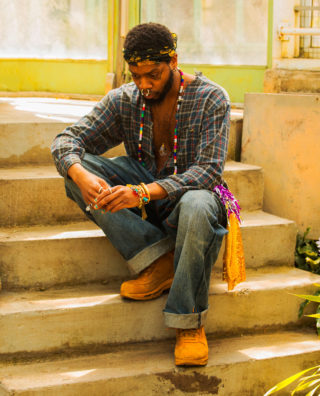

Serpentwithfeet first made his name in 2016. There’s a good chance you saw him before you heard him. Here’s the thing: serpentwithfeet has a large pentagram tattooed on his head, along with, in thick capital letters, the words “HEAVEN” and “SUICIDE.” (He has grown his hair out since then, obscuring the text, but the pentagram still occupies prime, visible real estate). He has a silver septum piercing that’s roughly the size of an eyeball, along with a variety of other pieces of jewellery. At the time, he sported a shaved head and strategic eye makeup that made all this defiantly apparent. The look was fierce, with an undeniable whiff of the satanic. The same can be said of the name serpentwithfeet itself, a reference to the prelapsarian snake, the form assumed by the Christian devil to tempt Eve to eat from the Tree of Knowledge. Altogether, it certainly grabs your attention.

It was a surprise, then, when the man wrapped in the iconography of the occult sang like an angel. On his stirring first EP, ‘blisters’, serpentwithfeet mixed classical and electronic music with a voice fluent in the sounds of gospel and RnB. If that combination wasn’t unique in itself, the intensity of the approach was. A full throttle fusion of each genre at its most melodramatic, serpentwithfeet’s music was a hell of a strong cocktail.

Released by TriAngle Records, whose founder Robin Carolan is also serpent’s manager, ‘blisters’ featured five concise but intricate tracks that explored queer experience. Label-mate and Bjork-collaborator the Haxan Cloak produced. It’s a pairing that made sense. The Haxan Cloak’s heavy and ominous soundscapes paired nicely with serpentwithfeet’s surface aesthetics: eerie, arcane, occult. Refracting its themes through a dark prism, ‘blisters’ treats love as something eerie, mystical, and transcendent in equal parts. The EP featured the stunning ‘four ethers’, a blend of baroque strings, ominous drums, and serpent’s soulful voice. The title refers to an esoteric concept that lies somewhere in the intersection of philosophy, astrology and paganism; it’s obscurity is largely the point: ‘Your name is impossible to know / You’re like my four ethers / How the hell do you know the four ethers?’ In the accompanying music video, serpent is dressed in flowing red, orbited by hovering points of weird, golden light.

Immersed in Haxan Cloak’s dark and immersive production, replete with references to karma, ethers, and retrograde states, ‘blisters’, and by extension serpentwithfeet, was infused with a sense of the mystical. Love was a gnomic mystery and the man singing about it had a strong link to the supernatural, with one foot in our realm and another foot someplace beyond.

In person, however, Josiah Wise is a deeply grounded individual. He mulls over his word choice and speaks with intention, softly and slowly. He is a fountain of practical wisdom (hint: get your probiotics) and musical knowledge. More importantly, he has a strong command of who he is as a performer and a person. That security is central to ‘soil’, an album firmly rooted in the physical world, in which serpentwithfeet’s vision of love is less mystical but no less sacred.

Many of the songs on ‘soil’ have been fermenting for years. The lush lead single, ‘bless ur heart’, started to form in 2009 when Wise was a senior at Philadelphia’s University of the Arts. It took him nine years of personal and musical growth to reach the version that concludes his personal album. In some ways, however, the process of fermentation goes back even further. Wise’s extraordinary sound has been developing since his childhood in Baltimore, where he was immersed in the music of the Christian church, when he began to formally hone his voice at age eleven.

White wasn’t initially interested in classical vocal training. When his mother asked him if he wanted to try out for the Maryland State Boys Choir, he responded with a firm no. But that didn’t matter to his mother, who had already signed him up for an audition anyway. “As an 11-year-old, I was like, ‘I can’t believe you!’ But she was like, ‘Boy, you are the child and I am the mother.’ So I went, I auditioned, and I ended up loving it.”

This was serpent’s first serious introduction to classical vocal performance. Even as a preteen, however, he began to encounter to the problematic aspects of the choir’s culture that would influence his relationship with the genre for years to come. White was troubled by the lack of diversity in the choir and the class undertones of “lofty classical songs.” “There wasn’t much room for the black voice,” he explains.

Fortunately, he was able to find a better home for his gifts when he entered high school, Baltimore City College, a public magnet school for gifted and talented students. In addition to a strong academic program, Baltimore City College was home to an internationally competitive choir. By the time he was 14, White was traveling with the group to Europe to compete and coming home with trophies. More importantly to him, though, was the makeup of the group. “It was all black kids, but our repertoire was predominantly classical. And that blew my mind.”

He committed to developing himself as a world-class vocal performer. Every day, he spent three to five hours singing after finishing class. That still wasn’t enough. After learning about an exceptional vocal teacher at Morgan State University, he called her almost every day for a year. One day she finally answered, White remembers, “and she said, ‘Boy, come.’” The lessons set him down a path to becoming a classically trained opera singer. By the time he graduated from University in the Arts, he’d mastered his instrument and developed a working knowledge of French, Italian, and German. He casually recalls taking Russian diction classes so he could perform ‘Lensky’s Aria’ by Eugene Onegin. “I wanted to perform in the opera houses, I wanted to perform at the Met. I really wanted that life,” he reflects.

But when Wise was ready to take the next step in his career, a roadblock sprung up in his path – he didn’t get into the graduate vocal programs to which he’d applied. The traditional trajectory he had followed so closely for so many years suddenly fell out from underneath him. Shut out of the classical world, he had to find a new way forward, and fast.

The years that followed were difficult, but formative. Wise travelled, moved to New York, worked whatever jobs he could find. He explored and embraced his sexuality; he loved and lost. He got the tattoos on his head. When he could, he recorded music, experimenting outside of the classical domain and throwing the results up on Soundcloud. Reorienting his stance on the classical world was an important part of this process. “So much of my self-esteem relied on that, but I couldn’t see it for a long time,” he remembers. “I wanted this world to give me the green light, but it proved to me that there wasn’t a space for me there.”

But if the classical world seemed to reject him, he didn’t reject classical music wholesale – his music makes that obvious. He retains an obvious passion for the genre; indeed, that passion seems to have only grown as his interest in other genres has developed, and he remains a wellspring of knowledge on the subject. At one point he digresses to explain the genius and influence of Czech composer Antonin Dvorak, casually offering a rundown of his work, complete with composition dates. Dvorak’s 9th symphony From the New World, which was called “the greatest symphonic work ever composed in [the United States]” when it was first performed in 1893, was profoundly influenced by African-American music.

“He sat with older black folks and indigenous folks of America and had them sing their traditional songs to him. He was heavily inspired by black American spirituals,” serpent explains. “Dvorak basically said that if America can get over this racist shit, African American spirituals can be the new frontier for classical music.”

While Dvorak was in the United States writing From the New World, he taught the violinist turned composer Will Marion Cook, a composer of particular importance for serpentwithfeet. Marion Cook wrote the first black musical performed on Broadway, Clorindy: The Origin of the Cakewalk. Serpentwithfeet stumbled on his biography and was blown away by the breadth of his influence. He was equally stunned by how little he had ever heard about Marion Cook’s story. “I read this book from cover to cover,” he remembers. “Before him, there was no syncopation, or many of the characteristics we think about with Broadway. He brought that.” And yet no one had ever taught this to him. “I’m just like, I should have known that.”

The expulsion of African-American innovation from canonical narrative is just one more unfortunate example of a culture of exclusion that continues today. Serpent reflects, “For me, knowing how much of our music shapes not only white classical music, but shapes pop music… Think about all the whimsy you hear in trap music, and how that influences pop music. All this stuff is stuff that black kids are doing in the middle of nowhere, that are anonymous.”

Serpentwithfeet’s response to this century old story is to follow the path of Nina Simone and Kirk Franklin, who he cites as inspirations. Both Simone and Franklin were and are exceptionally gifted classical singers who invested their talent outside the classical realm and have had an extraordinary influence on music at large, classical and otherwise.

“There’s this thing where black people, and I speak for myself, want to be a part of the black classical world. That’s fine if folks want to do that. I wanted that, and I do think there needs to be black people everywhere, no matter what genre. But there’s many of us who are vying for a position in this white classical canon, not even understanding that there’s so much weight around creating your own thing.

“I’ve always known black people to be part of the classical world. Historically, we know that black people have their handprint on classical music, [because] black music is so expansive,” he says. “It’s easy to get miffed by not getting accepted by white people. It’s easy to want to be a part of that conversation. But I’m like, we have the juice. We have the ideas. We have the soil. The soil is literally with us.”

Serpentwithfeet is a child of this realisation; if the classical world would not have him, White would have to build a world for himself, one that could be home to his many prodigious gifts. He cites Nina Simone and Kirk Franklin as inspirational examples of classical singers who invested their talent outside the classical realm and had an extraordinary influence on music at large.

“If you want to play Chopin, if you want to play Schubert, do it, but if you don’t get in, if you don’t get to play at Carnegie Hall, that’s not the end. Do your own thing. If you want to do Brahms, then girl, add a trap beat. You can make it your own thing, there’s not just one lane.”

This idea is central to serpentwithfeet’s first full-length. “With ‘soil’, I was thinking a lot about how I have my own goal,” he tells me. “I want to invest in what comes out of me naturally.” But a great many things naturally come out of him, from gospel to snares. On his remix of Bjork’s ‘Utopia’ track ‘blissing me’, he sings, ‘I don’t have enough clothes to dress all the people I’ve become,’ but ‘soil’ is in many ways an attempt to do just that – to draw together all of serpentwithfeet’s disparate selves and wrap them in a strange, single whole, while still honouring each of the things that renders them unique.

Coming in at just under 40 minutes, ‘soil’ is an economical album crafted with precision. Serpent worked with four producers that reflect the range of his interests and influences: producer mmph and sound designer Katie Gately (two of serpent’s TriAngle labelmates), hip-hop producer Clams Casino, and the prolific Paul Epworth, best known for his production for high-profile artists like Adele and Rihanna. But while each of these producers brought something of their own approach to the record, the sound is ultimately Wise’s.

“Before this project, I don’t think that I felt so confident as a producer,” serpent recalls. “I knew that I had ideas, but I don’t know if I let them carry as much worth as they could. So working with Paul Epworth, Clams and Katie, and mmph, I felt like, after those studio days, I felt a little more grounded in my knowings, a little less shakeable.”

Wise often turned to producer’s when he needed direction on how to reach his final destination. He recalls asking Gately to help him create the sound of “flamenco in metal heels,” and mmph remembers working to capture the sounds of Pop Rocks and sticks falling down. At times, they looked past instruments to get the sound they needed. Gately remembers using bowling balls on ‘bless ur heart’ to create the sense of something living underground. “It’s not just the sounds, it’s how it all fits into his world,” mmph tells me.

“All the songs changed until the final day,” serpent remembers. “I wasn’t comfortable with songs just being good. I wanted the songs to feeeel as explosive as possible. I wanted them to feel incendiary. I needed them to feel combusting.”

Some of ‘soil’’s qualities are easy to identify. “I wanted this album to dance more. I wanted it to dance, I wanted it to vibe heavy,” says serpent. “But most importantly I wanted the vocals to really come through. A lot of that is just mixing. I chisel production, I definitely chiseled and subtracted things. I never wanted the production to eclipse what was going on vocally because text is so important to me. I take a long time to work out how I want to say things and how I want to sing things.”

The production of ‘soil’ may have been a collaborative learning process, but the lyrics were all serpent. As a lyricist, White as a knack for small, sensory details. There is a deeply sensuous quality to ‘soil’, in its music and its lyrical content. Unsurprisingly, the record has an earthy texture, and the language is rich with imagery of roots, trees, seeds, things that live and grow in the dirt. More generally, his language has a fierce physicality; he has a gift for capturing the tactility of the language he uses in his music. Mmph recalls Wise using the term, “seeing where the body takes you” as a way of feeling out whether songs had this quality. When he sings “I love you from the space beneath my feet,” on the album’s extraordinary opener, ‘whisper’, Wise channels the emotion up through his body. Listening to these songs, it’s as if you can sift through them with your fingers.

The record also has a powerful scent, if such a thing is possible. Songs like ‘fragrant’ and ‘waft’ are explicitly aromatic. “I think about smell often,” serpent says. He claims that his sense of smell isn’t more attuned than anyone else’s, but then recalls with a smile, “My Mom would say, ‘You have a witch’s nose!’” It’s hard to disagree. While working on the album, he was interested in the theory that smell has a powerful impact on romantic relationships. In some schools of biological and psychological thought, it’s argued that partners unconsciously seek each other out by smell. This has certainly proved true in Wise’s case. “So often I will smell men before I see them,” he says. He recalls one time at a party in London where he caught a whiff of someone behind him. “It was a funky, pungent smell, and it was so beautiful to me. Out of the blue I was really turned on.” So when, on ‘waft’, he sings, “there can be no love where there is cologne,” he means it quite literally.

Wise engages with the writing process very differently than he does performing. Indeed, as a writer, he seems capable of maintaining an impressive degree of detachment. All the songs on ‘soil’ confront the practical and emotional demands of love, never shying away from the pain that comes with the experience. But none of the songs emerge from a specific relationship, despite their seeming specificity. “I want to be careful when I write that I don’t exploit my own romantic life, because I think that can become abusive to the people I date and abusive to myself,” he says. “I can talk about men that I used to be with and not break down, in the same way that I can talk about my favourite TV show that got cancelled.”

But when he performs, or even listens to some of these songs, he can be overcome with emotion. ‘mourning song’, where he sings, ‘I make a pageant of my grief,’ is the best example of this. “Every time I listen to it, I’m almost in tears,” says serpent. A song about sadness doesn’t have to be sad, though. Wise says that that track is one of the most fun songs in his repertoire to perform.

In recent years, it has become increasingly important to serpent to experience sadness in this way. He returns to the idea of fermentation. “Grief is like that live bacteria,” he says. “It’s good for you to miss and to long and to wonder, and not regret, but reflect. Running away from your grief is why people are sick. I think it’s really good for your stomach to weep, to weep uncontrollably,” he says. “Being sad doesn’t have to be this sad, isolating thing. It’s like the film Babadook. You cannot run from your grief. The more you run, the more it’s going to knock. And it’s gon knock, and it’s gon knock, and it’s gon knock. You have to feed it!”

These days, Wise sets aside time to laugh and time to cry. He doesn’t bury feelings so much as plant them, and the result is a personal and artistic blossoming. It seems that he couldn’t have one without the other. As he gets ready to leave, he suddenly speaks at length and with an urgency he hasn’t used all day:

“In America, there’s this fast track. You go to college, you get a job, you get a retirement plan, and you die. But it doesn’t have to be that linear. It can be, ‘you go to college, you drop out, you go back to college, you become a veterinarian, you become a vegetarian, you become Atheist, you die and you come back to life. There’s so many ways to exist.’ I think I always thought, ‘I have to graduate from undergrad, then go to grad school, then go to the opera house, then I’ll become a fabulous opera singer, and then I’ll die.’ That’s how I saw my life. I didn’t know, ‘Ok, you’re going to be broke, you’re going to be unemployed, you’re going to fall in love with a boy, you’re going to think that you wasted time and realise you didn’t waste time. You fell in love, it invigorated you to love yourself more, and then you’re going to write a song. Then you’re going to be a little bit stronger.’”

There’s no summation better than that. Wise finishes, resumes his thoughtful and collected manner, and gets up to work on the next thing. But like ‘soil’, which took nearly a decade to ferment to the point ready for public consumption, it seems like serpentwithfeet is content to let new ideas set and germinate for the future. When asked about future plans, he keeps things general. He wants to move somewhere warm. “Sweating is an important part of my process,” he notes. But most of all, he says, “I want to garden. I want to play in dirt.”