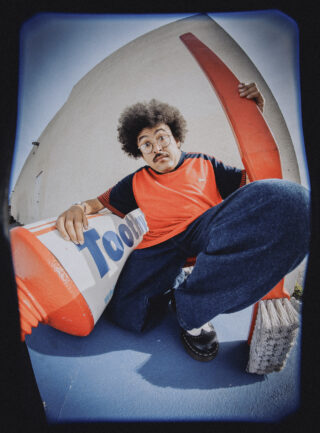

Cola Boyy: the revolutionary politics and squelchy disco of Matthew Urango

Addictive anticapitalist pop from Oxnard, California

Addictive anticapitalist pop from Oxnard, California

If all you knew of Cola Boyy was his music, you might expect someone at least a bit zanier and more light-hearted than Matthew Urango. Where his music is funky, heavily indebted to the squelchy disco revival that’s trickling into pop music at the moment, when we speak over Zoom one evening in May from his home in Oxnard, California, Urango is serious, considering each of my questions with great care and gravity. He is loquacious, but every word is chosen carefully; he rarely allows himself to crack a smile, and he appears to really resent any occasional interruptions to our conversation, admonishing his dog for barking loudly and rushing off-camera visibly annoyed at one point when someone knocks incessantly at his door.

His forthcoming debut album Prosthetic Boombox plays with this duality very cleverly. Wrapped up in the shimmery nostalgia of funk basslines, Chic-esque guitars and soft keys, Cola Boyy is Urango’s way of slipping subtle political messages into what’s just a very good pop album. “I would consider myself a revolutionary artist, or the people’s artist, more than anything. I studied Marxism and other revolutionary theory, so I would call myself a Marxist,” he clarifies – his press release describes him as “a devoted communist”.

So what role do his politics play in his music? “Pop music is very infectious,” he says. “It’s palatable and people like it, it reaches people’s ears, gets stuff in people’s heads, and if I’m trying to convey an idea or a message, how better to get it out there than in a way that’s catchy as hell?” He explains, “Of course, most music under capitalism is literally controlled by the bourgeoisie, so a lot of disco in the ’70s was very bourgeois. It was very decadent and escapist, and in the ’80s music was very emotional, all about love and partying. I understand those types of topics are very synonymous with my style of music, but it doesn’t mean it has to be that way. You can write a catchy song that still has meaning and is going to serve the people and their struggle.” He pauses and says, “It’s also a fun challenge for me: how can I make a catchy song that’s relatable on a broad scale, that conveys a message or experience that people can relate to, but that’s also not preachy and shoving politics down everybody’s throats? Nobody wants that, that’s not how you win people over. You win people over through relating to them and trusting you, them seeing themselves in you.”

Born and raised in Oxnard, California, Urango involved himself early on in the city’s vibrant punk scene, which is where his political sensibilities began to form. After learning to play guitar and piano as a child, he began playing in bands and writing snatches of songs as a teenager. Though the punk politics of the scene “were very emotional and not very precise”, it taught him the possibility of rebellion in any given situation. While his current musical output is a far cry away from his gritty punk roots, Urango says the scene influenced his musical ideology of taking whims and running with them. “I’m not very limited in where I’m willing to go on a musical level,” he says. “I just don’t give a fuck, and if I want to make a song that sounds like this, I’m going to do it.”

From the opening song on Prosthetic Boombox, ‘Don’t Forget Your Neighbourhood’, both Cola Boyy’s politics and carefree attitude to music are abundantly clear. Urango’s strident, slightly nasal voice rises above chirpy piano stabs and dreamy chimes to profess a message of community; a call to immerse yourself and uplift those around you. Even the album title is a coded reference to Urango’s own disability: he has spina bifida and wears a prosthetic leg. Originally, ‘prosthetic boombox’ was the title of a song that Urango wrote five years ago. “When I wrote that song,” he remembers, “I was on the path of resolving a lot of self-esteem issues, anger and bitterness, becoming more accepting of my circumstances.” It also references the fact that Urango always wanted his debut album to sound like an eclectically curated radio show, with lots of songs drawing on different genres, hence ‘boombox’. “It had its meanings, but also if people don’t know what the fuck it means, it sounds cool,” he concedes.

Being more open about his disability and letting go of how people perceive him is a prominent part of the album closer ‘Kid Born In Space’. “I’m talking to my old self, in a way. I’m telling myself, all those years that you were upset or angry, you don’t gotta have those feelings,” he explains. “None of us are taught why we’re treated the way we are. The root of why disabled people are alienated is that they’re not able to join the workforce, therefore they have no value under capitalism. That’s why you’re taught to alienate disabled people at a young age. Once I realised that, I stopped being mad at people, even though people bullied me, because I realised that they have stuff going on at home too that they’re struggling with. So I think ‘Kid Born In Space’ is kind of an anthem to that.” Originally an upbeat disco tune, inspired by the proclamatory joy of Diana Ross’ ‘I’m Coming Out’ and Urango shedding the weight of outside expectations, he reworked it with Andrew VanWyngarden of MGMT, with whom he became close after supporting the duo on tour. It was VanWyngarden who suggested slowing it all the way down, and lo and behold the song was formed.

As a musician with a visible disability, Urango says that he finds it hard to balance being open about his life with being reduced to just that guy with a prosthesis. “Something that’s a big part of the resolve that I have with myself is being open about my disability, and my understanding of the world and myself isn’t something I’m doing to further set myself apart from others. Through understanding the world around me through an end-to-capitalist standpoint, understanding economically how all these things are connected, I want to relate to people more. I want people to know about these things, not so that I can further distinguish myself, but so that I can lessen the space between us. Maybe people would be like, I have no idea what it’s like to be disabled or have a prosthesis, but that’s not the point. The point is that the system that we live under created these conditions for me, and they created the conditions that others are experiencing, so raising that understanding through my music or platform or even in interviews like this is really what my goal is.”

This idea of bringing people together is also pertinent for the musical creation of Prosthetic Boombox. It features collaborations with the likes of MGMT, Myd, Air, The Avalanches and Connan Mockasin, which are all admittedly big-name features, although Urango is clear to say that his professional endeavours with them came about through genuine friendship and a desire to elevate the music rather than his own profile. Philosophising briefly, he says, “collaboration is important in so many aspects of life, and it’s something we’re taught not to do. We’re shaped to be individualistic and cut others off. There’s a tendency in music today to be like, I did all this, it’s all me. I understand there’s a sense of wanting to have creative control, but nothing compares to working with others. There are things that I can’t do that I want to heighten my songs. I want my songs to be the best possible and I put that over my own ego. What matters is the final product and whether people like it, cos at the end of the day, they’re not really going to give a damn if I did this, that and the third. They just want the song.”

Urango has been harnessing the power of his songs recently to find new ways to involve himself in politics. Though he has previously been very active in grassroots political movements as a member of the Todo Poder Al Pueblo collective (a small far-left group that fights for immigrant rights in Oxnard), he has decided to take a more consciousness-raising approach as his music takes up more and more of his time; he recently played a concert in Oxnard raising awareness of the plight of the people in Rondônia, Brazil, who have seized land from their landlord and now 150 families are facing government-sanctioned massacre. Through playing gigs like that, he’s found he can draw in a bigger audience to his political endeavours.

Marxism wrapped in a disco disguise, Cola Boyy exudes a revolutionary optimism that is at once intimidating and galvanising. He says that he’s heartened by the protests that swept the world last year against police brutality as a sign that “the whole world is dying, and the new world is struggling to be born.” He is also clear that whatever role he plays in this, ultimately his part is not important: “I’m just one person, I’m not going to make history. It’s the masses that make history.” Regardless of whether or not that actually transpires, Cola Boyy is perhaps the reminder everyone needs to gird your loins, do your bit and get stuck in.

Photography by Ross Harris