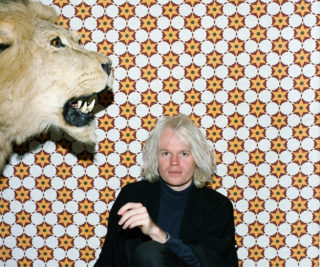

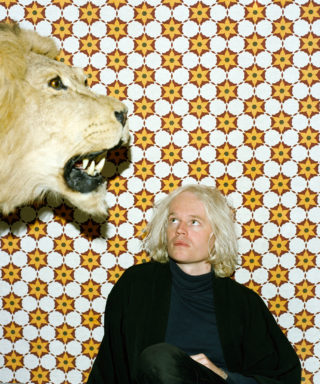

Surrounded by dead beasts, Connan Mockasin discusses new album ‘Caramel’

Animal Charm

Animal Charm

“That polar bear has no neck. It’s like a sausage with a face on it.” Connan Mockasin, née Tant Hosford, is from Te Awanga, a small beachside town on the North Island of New Zealand. He’s 30 years old, although he looks younger and radiates another time. The cosmic end of the ’60s, or some dimension we don’t know about yet. To say he has an aura about him is not to be melodramatic, and to call that aura ‘otherworldly’ is as accurate as the sausage neck.

For the record, Connan is referring to an actual polar bear, although he is just as likely say something along those lines in an empty room. As Erol Alkan, the man who releases Connan’s space soul through his Phantasy label, says, “He has an amazingly vivid imagination,” and it’s made a fan of Julian Barratt, who during this afternoon will, on a number of occasions, text Connan ahead of them meeting for the first time later today. He’s asked if he can direct Connan’s next video, a first for the Mighty Boosh’s Howard Moon, who is currently rehearsing a new stage show with Noel Fielding a couple of blocks away. Even the artwork for Connan’s debut album, ‘Forever Dolphin Love’, is ripe for the absurdist world of the Mighty Boosh. It features a self-portrait by Connan that looks more like coconut-headed Boosh anti-hero Milky Joe. Connan then spent a year dressed like the painted portrait, his face flaky with white powder.

He’s got an idea for a stage show of his own, where he plans to dress himself and his band in uniform, non descript clothing, and his bassist as a centaur. The bassist – a guy called Nick – will also be under a spotlight. These ideas just come to Connan, and when you ask him how, he can never seem to remember.

The concept behind new album ‘Caramel’ is similarly hazy, featuring the dolphin from Connan’s debut and ‘The Boss’, who is sad because he loves the dolphin, which is leaving. The Boss gets over it and is happy again, but then there’s a car crash. “There’s a story that goes along with it, but it’s really not very good,” Connan dismisses. “If it was a book it would be appalling.”

This morning, having played a one-off, sold-out show in London the night before, Connan awoke to flowers in his hotel foyer, a gift from one of his fervent admirers. He left for an early morning walk where he was approached by two equally farcical characters. The first, he says, was a man who’d been stung by a bee on the top of his head and wanted advice on whether he should go to hospital or not. “I asked him if he was allergic to bee stings and he said no, so I told him he should be alright. I don’t know why he asked me – I mean, do I look like a doctor?”

Next Connan met a young girl who may or may not have left the flowers, and who may or may not have been staking out the hotel all night. She ran across the street and proceeded to tell Connan about how she had come to the show last night and how at the precise moment he played ‘Dolphin Forever Love’ her wristwatch, emblazoned with what else but dolphins, miraculously began working again after years of being broken. Spooky right? Well, how about this – the time was only 2 minutes out! Connan went back to bed.

But yes, the polar bear. It’s big and sausage-like, but it’s nothing compared to the one downstairs. The King’s Head is a very particular members’ club in Dalston, London, an area of town where members’ clubs don’t exist. Its exterior fits right in, but behind the crumbling, sooted pub façade is a zoo of opulent taxidermy. A tiger looms over the island bar downstairs, and a rearing, 12-foot polar bear over club diners on the first floor. We take our place in a meeting room at the top of the stairs, which is completely outrageous. We join two lions and two tigers, a leopard, a panther, a cheetah (I think it’s a cheetah), the polar bear and the heads of two unfortunate zebras protruding from the fireplace. The elephant foot umbrella stand and hooved lamps are hardly worth mentioning. It’s deadly silent and powerfully relaxing. A room of good-looking death, it’s sexy and unnerving at the same time, not unlike Connan’s new record, released next month on November 4.

‘Caramel’ is named after its sole, literal influence – the sticky, smooth confectionary that you’ve never thought of as glamorous until now. Connan liked the onomatopoeic quality of the word, and so decided to write an album around what it means to him. I’ve obviously been going to the wrong sweet shops. “It’s just smooth, easy music,” he says in his soft speaking voice that lilts with the calming accent of Te Awanga, but it’s more than that. ‘Caramel’ is a melancholic, outsider funk record that is blissfully unaware of current trends, largely because Connan hasn’t bought any new music in ten years, and because he doesn’t do the blog-trawling thing either. There happens to be some similarities to Ariel Pink on the skeazy ‘Do I Make You Feel Shy?’, and to Mac Demarco in the title track’s half-speed spoken introduction, but that’s down to coincidence rather than homage.

Connan opted out of the conventional pop world as soon as he entered it in 2006, having left New Zealand for London. Had he not, there’s a good chance that he would never have written ‘Why Are You Crying?’, ‘Caramel’’s 6-minute drunken waltz that features sobbing where words should be. “And that’s real crying,” he says. “It started as fake crying but became real crying.” I tell him that the track creeps me out a bit. He looks at me perplexed.

‘It’s Your Body’ would have been a no, no, too. Instrumental and split over parts 1 to 5, it makes up half of the album. No label was going to get that, so after a year of being courted by record companies in London, and another in Sussex once the city had become too suffocating, Connan Mockasin flew home to New Zealand, concluding that the UK music industry was no place for him.

“I just wasn’t impressed with the way they were trying to make you do particular songs,” he says. “There’s basically businessmen trying to make records, and I found the whole thing really depressing so I came home after a couple of years. Y’know, they dangle money in front of you, like, ‘you don’t want to have a day job, have an advance.’ So I found that I didn’t want to go down that road, so I went home and was just hanging out at the beach.”

We’d probably have never heard of Connan again were it not for the encouragement of his mother who insisted that he should still record an album, just for the hell of it. “She was like, ‘you should make your record; you’ll make a good record’, but I was like, ‘I don’t know how to record or anything, and I’m not very good…’, but my mum is very good at encouraging, so I just did it for no reason, not thinking it’d ever get released, and I couldn’t imagine playing the songs live or anything, and then Erol Alkan stumbled across it. I didn’t play it to anyone – I was so embarrassed by it. I played it to my mum of course, and then Erol was probably the second person and he wanted to sign me, so I was like, ‘alright, you seem like a nice person, a bit different to the normal label people.’ And here I am now. It’s all a bit weird.”

‘Dolphin Love Forever’, originally released as ‘Please Turn Me Into The Snat’ in 2010, was constructed as it was presented, innocently in order, with Connan feeling his way through the record and writing each song on the fly, depending on his mood that day. “I was like, ‘this sounds nice now,’” he says, “rather than having songs and putting them in an order – I hate that. It’s not a record, it’s singles and then, okay, here’s the sensitive, acoustic, quiet track, we’ll put that at the end, this is for radio – it’s just crap. It seems like there’s so much rubbish out there now, and it’s all designed to make money. These people should get into property or something like that, but I suppose you don’t get the fame with that. It’s usually people wanting to be famous and other people wanting to make money out of them, so it’s a real bad mixture.”

Connan pads around The King’s Head in his blue socks, a man that grew up outside but now spends most of his time indoors, since moving to Manchester earlier this year. It’s a city he’s still at odds with, but, then, London never bowled him over on first impression either. “We’re in a really rough part of Manchester,” he says, referring to himself and Manager Sophia, also present and originally from France, a nation most in love with Connan’s eccentric pysch pop. “We’re in Walley Range, but the house is really nice so I just stay inside.” He laments a time when he was more in touch with nature, in the Sussex town of Lewes and in the vineyards of Te Awanga, where he figures he’d be working were it not for his mother’s encouragement. “You just need somewhere that’s relaxing, near to an airport and where it’s nice to go outside. That’s important.”

Connan surfs, too, which suits his tangled, shock-blonde beachhead and messianic, stars-aligning whisper. I’m surprised to hear that he’s never tried meditation, although he imagines it’s a lot like surfing, or playing live – activities that exist wholeheartedly in the present. “When a live show is right, it’s over like that,” he says, clicking his fingers.

He says that he misses New Zealand and the very thing that most young people strive to get away from – the isolation of the place. “It’s quite closed off to a lot of stuff,” he says. “Even with the Internet it takes a long time for things to reach there. It’s just so far away, which is also good, because you feel completely isolated there, so I can go home and it’s like a retreat for me now.

“People always go New Zealand and go to Christchurch and Auckland, but they’re the worst two places. They’re the two biggest places, but you wouldn’t go to New Zealand to go to a city – that’s not what’s good about it.”

Connan’s parents still live in the house they self built in the 1970s for themselves and their three sons. Nearby Connan’s aunty and uncle introduced him to popular music via ‘Star Trekkin’’, the 1987 parody hit by The Firm. “Klingons on the starboard bow, starboard bow, starboard bow,” sings Connan, quietly to himself. “I loved that. Every time I’d go to my aunty and uncle’s I’d get excited about stupidly dancing around to that.”

Then hair metal reached New Zealand television and Connan liked what he saw, if not what he heard. The long hair, the leggings, the sleeveless shirts, the Star Spangled bicycle shorts – his eyes had been opened to the dress up of pop. “I didn’t particularly like the music, but I wanted to do that!” he says. “Then Michael Jackson came along and I loved him like every kid did.”

Now, mention Michael Jackson to me and you’re never going to get that time back. His was the first gig that I went to, and since his death, especially, it’s a story that’s quadrupled in kudos, but with Connan, I may have met my match. He already knows every detail about the show I saw, without having been there himself. The rocket entrance, the roller coaster, the countdown, the kids on stage (okay, there was always kids on stage); he reels it off. “One of my friends was one of those kids when he came to New Zealand, and without their parents begin told they were all given Rescue Remedy in pills or something, so that was kind of weird. And then my friend tried to run off and jump into the crowd and Michael held him back. But yeah, he was a big thing, and then I took up guitar because a friend was doing it as we were moving up to middle school.

“I remember watching Under Siege [the Steven Seagal movie] and then there was this… [Connan impersonated the intro to ‘Voodoo Child (Slight Return)’] …and I was like, ‘What is this?!’, and my parents were like, ‘this is a guy called Jimi Hendrix, we’ve got a record of his upstairs’, and from that point I wanted to play the guitar like him, so I just practiced for a year or two.”

Connan has become a much more accomplished guitarist than he’s so far been given credit for. His felt hats, bewitching falsetto and general cosmic being can pull focus from what he’s doing with his hands, but as a musician he has a natural, loose way of playing the only guitar he’s ever owned, like an old blues player that’s got it in their blood. It’s what gives ‘Caramel’ much of its eroticism and boudoir soul, yet Connan feels that the guitar has had its day, not to be replaced with electronics (“I don’t know anything about that – I like instruments that you have to physically touch”), but something else, something completely new. “I think it’s overdue time for a new instrument, and it has to be something that’s very expressive,” he says. “Like, a guitar is very expressive and it took, like, hundreds of years to get to where it is, and it’s portable and it’s an actual thing that you actually play, y’know, it’s not electronic. I reckon there has to be a new instrument at some stage, but again, it might take hundreds of years to get here.” He gives in to the urge to stroke the polar bear’s immaculate white fur.

‘Caramel’ is a record for all your bedroom needs, from lounging to sleeping to the other. It exists largely in that bewildering space of semi-consciousness – the pockets of snooze time where your brain decides that anything goes. A dolphin, The Boss, a car crash – sure, why not? It’s merrily without conventional structure and was recorded accordingly, in a hotel bedroom in Connan’s favourite place in the world, Tokyo. Japan, he says, is “kind of sexy. It excites me there, and I like having limitations and I don’t really like studios, so I just locked myself in a room for a few weeks. It was not far from Lost In Translation.”

Tokyo is Connan’s megalopolis service station when he’s travelling between England and New Zealand. From the first time he stayed the night, he felt an affinity with the place, telling me, “It was so foreign and strange to me, but I felt weirdly homesick when I left – really down, even though I was only there for a night – and I have that every time I go there.”

He decided to record ‘Caramel’ en route back to the UK, having flown home to visit his father who was close to dying. Once on the road to recovery, Connan holed himself up in a Tokyo block and opened his door to friends to stop by. He had a lot more by the time he left, but people act more as inspiration and company to him, rather than collaborators. He’s written songs with Charlotte Gainsbourg before, and last year toured as a member of her backing band (the rest of the band were Connan’s touring group), and he’s recorded a whole record with Sam Eastgate of Late Of The Pier, to be released next year under the name Soft Hair. But he’s happiest working alone and completely free.

It’s difficult to think how you’d go about writing music with Connan Mockasin, anyhow, considering he doesn’t exactly write songs. “I like stuff that surprises me,” he says. “I never write on guitar or anything, I don’t sit down to make music. I’ll be doing something else completely unrelated and it’ll just come to me – everything, the whole thing. And when I record it I don’t try and work it out, I record it straight off as I can hear it, and it’s usually a bit messy, but I’ll leave it for a day and then I’ll be like, ‘actually, I quite like that.’ I like catching that initial thought.”

‘Transient’ is perhaps the best word to describe Connan. He is himself, bouncing from New Zealand to Japan, to London to Lewes to Manchester, to France with Gainsbourg, always feeling at home but never staying long. It reminds me that we have met once before, briefly on a roof in Barcelona. He was up there with his guitar, happily alone, from what I remember. I got the impression that he wasn’t stoned but rather a comfortably nomadic kind of guy, something to be envied, just as Erol Alkan envies Connan’s indifference to collecting music (“Being a music collector doesn’t make you any more of a connoisseur,” says Alkan). Musically, too, Connan believes in the naturally conceived, “catching that initial thought” to make ‘Caramel’ the weightless, ambient funk record – the smooth record – he wished for it to be. Unsurprisingly, he hasn’t listened to it since it was recorded, he says because he’s embarrassed by it (and by being a musician), but it’s just as likely that he feels it’s a moment that has passed.

And so I’m not surprised when he tells me that he doesn’t want to do this forever. But what else is there, I ask. “I’m really into carnival rides that fold up onto the back of trucks,” he says. “I like houses at the moment because I’m getting older and my dad used to draw houses. Drawing and painting is my main thing, actually more than music, and I don’t know how much more music I’ll do. I’m not sure if I’ll do another record or not, only if I get excited again. As soon as this becomes a job I’ll do something else.”