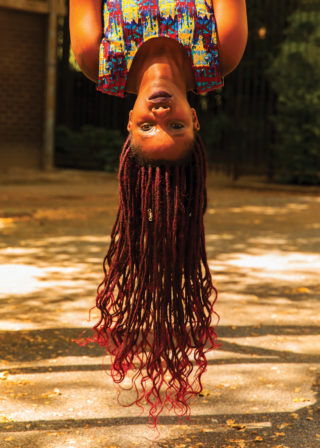

DJ Kampire – Creating safe spaces for women and the LGBTQIA community in Uganda and beyond

Speaking her truth, with compassion and care

Speaking her truth, with compassion and care

Usually finding yourself admitted to a Brooklyn hospital in the middle of the night would be a grim way to finish your Saturday night out. Although, being put there because you danced so hard at a DJ set that you dislocated your own knee puts a different spin to it. Thankfully my insurance-less self was not the person in question who ended up with a busted knee being cracked back into place in the early hours of Sunday morning but the person in question who sent the other travelling Brit there was DJ Kampire.

“I like it when it’s sweaty and people are into it,” she had told me a few hours earlier, before her set in a basement Brooklyn venue as part of the Red Bull Music Festival in New York. The inaugural UK version of the festival begins on August 20th and will showcase over 100 artists across 16 events, featuring the likes of Aphex Twin’s first London club show in a decade. Much like the New York festival, it spreads across the city in unexpected places: the day before Kampire performs the jazz collective Onyx Collective play an amphitheatre set on the waterfront whilst a week earlier FKA Twigs launches her comeback in an old drill hall. Back in the basement Brooklyn venue Kamipre got her wish as the air hung thick and sticky and the dance floor remained ever-shifting as she played a set of thumping pan-African sounds, spanning traditional Congolese rumba to African pop underpinned by a bass-heavy electronic stomp. DJ Kampire is from Kampala in Uganda and is a key part of the music collective cum music festival cum record label Nyege Nyege. The collective are proudly promoting the sounds stemming from east Africa, combining spinning polyrhythmic rhythms often blended with western techno beats and house grooves.

Music and dancing became an early and inherent part of Kampire’s life. “I grew up in Zambia for a while but my parents are Ugandan so we’d have these east African expat parties,” she recalls. “With lots of TPOK jazz, Franco and Kanda Bongo Man playing. The adults would get drunk and call the kids to come and dance for their entertainment. They would then pay us money to whoever won. I don’t think I overtly considered myself musical necessarily but there was plenty of appreciation for music in my household.”

Years later as a young woman Kampire found herself slipping into the world of DJing by accident. Roped in to help out organisationally at the first ever Nyege Nyege festival, she was suddenly asked to play out. “I began DJing by mistake entirely,” she says. “I was DJing off my laptop and I couldn’t really mix, so it was just one song after the other, but I knew that I wanted to play these bass sounds that are great to dance to but I wasn’t hearing in Kampala at the time; to play a lot of older African music. People responded so well to that set that I’ve been doing it ever since.”

Kampire’s sets have not only taken her across the world and landed her the title of one of Mixmag’s breakout DJs of 2018; her music comes with a form of political activism in tow. As a queer woman herself, Kampire and several other DJs have been going out of their way to throw a variety of parties back in Uganda that act as safe spaces for women and LGBTQIA people, as well as encouraging more women to DJ, which is still a relatively new occurrence there. “It’s a very diverse group of people that come,” she tells me. “It’s about creating spaces where people of different classes can get together – it’s also a city of refugees so you have real diversity of culture, as well as gender. It’s an open space where any type of person can come and party.”

Whilst in the west this may seem like a fairly standard and comparatively easy task to undertake, in Uganda homosexuality is still illegal and until a technicality annulled the Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Act in 2014, it was punishable by death – a law that was nicknamed the “Kill the Gays bill”. As a result, the LGBTQIA community still face serious danger and prejudice in the country and throwing a party that acts as a safe space for such people is a radical move. On top of this, violence against women in the country is also on the rise, and during 2017 and 2018 there was a spate of women who were murdered, many of whom were kidnapped from the street and sexually assaulted before being killed.

“When we throw queer parties which are outside of the Nyege Nyege festival, we definitely have to be more careful,” she tells me. “We can’t necessarily label them as queer parties because you might draw the attention of the wrong sort of people. Even when we are doing parties just for women – like the Pussy Party’s we throw – we are making sure that women are safe and looked after, so no straight male shenanigans are taking place. But if you advertise it that way then to an extent you create a backlash and attract those people who just want to come and fuck it up.”

It’s a juggling act for Kampire and her collective; creating a welcoming and inclusive space but also making sure it doesn’t encourage those who could wish harm to those in attendance. “We have different levels of parties,” she says. “So you might have an intimate house party where you have to be on the guestlist to come and there’s a password and you have to know what the party is there for. You want to make sure it’s a safe space for minorities but you also want make it more open to people, so keeping that balance has definitely been very challenging.”

Whilst the success of the Nyege Nyege festival, collective and record label has seen Kampire DJ cross the world spreading the word and rhythm of east African music, from Sonar in Barcelona to warehouse parties in Sheffield, her hometown of Kampala is still far from resembling an industry hub and having a network in place. “Nobody is in it for the money because nobody is making any money,” she says. “So you can at least be sure that’s not what is motivating people. I can appreciate the purity that comes from such a grassroots movement but in the West there’s this not wanting to be corrupted by corporate or profit interests, whereas in Uganda, because the market is so small and there’s no money, we actually want to prove that this is a commercially viable project to book underground acts.” It seems to be working. For the 2019 edition of the festival, which takes place in September, the line-up boasts a mix of local and international acts with genre-twisting underground artists such as Jlin, Rian Treanor, Errorsmith and Giant Swan all featuring on the bill.

Kampire is also hoping that throwing such parties and events will not only legitimise underground and eclectic music in Uganda but also help dispel some myths and negative assumptions associated with the place she proudly calls home. She tells me: “Whilst Uganda has this very conservative reputation both outside and inside the country, it’s also very liberal. The liberal side just doesn’t have the same PR. Ugandans are a very liberal people and Kampala is known as the party capital of east Africa. People come there because there are no rules to an extent – you can party very late, there are no noise regulations, so we’ve always had that outlet of entertainment that isn’t as politicised. There’s a huge conversation for Africans about being misrepresented and we have felt so misrepresented previously that we don’t want to paint this picture of Africa as a dark continent.”

At the same time, there are some truths that are unshakable and Kampire is more than honest about some of the negative aspects they have to face there at the moment. “Women’s safety is a massive issue all around the world but in Kampala I think it’s actually getting more dangerous,” she tells me. “I never want to say this to outsiders because we already have a terrible reputation but I’m seeing an increase in criminality and violence in line with the rise of equality. Women’s increased freedom leads to a backlash. We have a serial killer in Uganda who is killing women and the government is more concerned about squashing political opposition than protecting people.” She also mentions the imprisonment of musician and activist Bobi Wine, and the artist regulations they are trying to enforce that would severely restrict musicians being able to perform, as well as the recent social media tax in which the Government are charging people to use social media sites in a bid to censor people – or curb gossip, according to them.

Last year Kampire and the Nyege Nyege collective were on the receiving end of some malicious gossip themselves. “A couple of days before the festival our Minister of Ethics and Integrity decided that it shouldn’t go on,” she says. “There was this Whatsapp message that got forwarded saying that the festival is full of gays, that it’s coming to corrupt our children, there’s drugs everywhere, people are having sex with animals – it was super dramatic and not attributed to anybody. Days later the Minister comes out and does a government press conference saying the festival is cancelled and that it’s not happening. But other government people we worked with insisted we could go ahead; even people who ordinarily might not support something like gay rights issues were like, ‘no you’re not going to take this party away from us’, and so they found themselves on the same side as us.”

As the conversation goes on I become very aware that I’m probably yet another white westerner asking an African person about the problems in a place that I have never visited nor know very much about. Does this lead to a degree of discomfort, being appointed something of a de facto spokesperson often for an entire country when conducting interviews? Is Kampire comfortable with the political tag that comes with being a DJ from Uganda? “No, not really,” she says. “Firstly it was this kind of girl power DJ thing – like ‘Kampire a woman DJ’ – which was interesting at first. I felt like the conversation was stopping there but now that I’m having more in depth conversations I’m also worried about what the implications for me might be. It is worrying. I don’t want to be too overt about what I’m saying and put people at risk, so it’s hard for me to make sure that we are having a proper in-depth and representative conversation about what is happening in Uganda today, but also to not paint a picture of it as being a worse place than anywhere else in the world. I don’t want to increase the backlash against the festival and my own career as a result of these conversations. We just wanted to throw some parties and listen to music on some big speakers. We didn’t expect it would become this political thing necessarily, but it’s where we’ve ended up.”

Opting to finish on a positive note, we speak about the impact of being able to play this music around the world and to have sounds from Africa pummelling out of some of the best club sound systems in the world. “It’s hugely rewarding,” she says. “I don’t make my own music at this point, so for me to represent east African artists has been amazing, and to see people respond to it in a really primal and emotional way has been a massive privilege. I hope it happens for more African artists rather than me being held up as a representative or the expert or the only woman DJ coming out of Africa. I hope it opens doors for other people.”

For more information on Red Bull Music Festival London, 20 August – 14 September, visit www.redbull.com