During the stages of planning this interview and brief gallivant around Leeds, Eagulls decided upon the first meeting point: the train station Wetherspoons, at 11am. I arrive to a packed pub that feels more like it’s 11pm, but that’s Wetherspoons for you, today full of early morning booze-hounds sucking down cheap ale, people inhaling grease-soaked English breakfasts, football fans fuelling up on their way to away games and a minority of people waiting for trains.

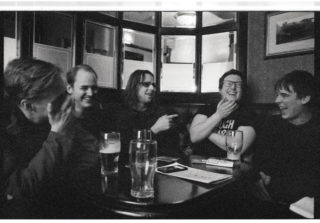

Eagulls arrive in dribs and drabs, singer George Mitchell and Guitarist Mark Goldsworthy first, shortly followed by drummer Henry Ruddel and bassist Tom Kelly, bleary eyed and with two hours sleep under their belts. Only hours earlier, at 6.30am, Henry had fallen asleep in the doorway of his local co-op next to a homeless man. Second guitarist Liam Matthews is the last to arrive and despite the visibly affecting hangovers of some, we all opt for a morning round of Guinness and beer. Eli, our photographer, is delayed due to a dog-rescuing mission, so we sit and casually talk for an hour before she arrives.

Eagulls have something of a prickly reputation if their press is to be believed, but it soon becomes clear that any unease around – or disliking for – journalists they have may well be grounded in some most justifiable footholds. The group informally recall a recent journalist’s write-up of an encounter, which took an innocent, flippant conversation the band were having about the rumoured register that exists if someone checks out Mein Kampf from a library, which was turned into a line about how the group sat around discussing “Nazi Shit”. Similarly, the band’s upcoming album release show is priced at £1.79, a price too steep for some writers who have already been emailing the band requesting guestlist. Their relationship with the press wasn’t helped by events last year either. 2013 started somewhat tumultuously for Eagulls when the band published an off-the-cuff, daft open letter to, well, everyone, largely deriding the current music scene of ‘Beach Bands’ and mummy and daddy-funded, trend-following, fad artists (“You do not surf. You are not gnarly. Stop saying dude, rad, bro… Shut your rich mouths”). The letter, when read as a whole, is certainly vitriolic but it’s clearly not something that has been well thought through – it’s a reactionary, spontaneous vent at some systematic issues found in modern music culture but at the same time it’s also purposefully, intently stupid and meaningless (“Gary Numan would knock all of your Dad’s out!!” is intentionally childish but all the funnier for it and perhaps is the single line that best captures the intended spirit of the letter).

Unfortunately, a small part of the rant could, somewhat understandably, be interpreted as being sexist, which resulted in something of backlash. The group feel that single point, misguidedly written as it maybe was, was picked up on and taken unnecessarily and uncharacteristically out of context and it is now something the band are keen to forget and move on from. (The letter has now been taken down from the band’s blog and replaced by a picture of a penis poking through someone’s buttocks with eyes drawn on them, with hands touching the tip of the phallus with the title ‘Letter closed. Fingers on Lips’).

The inevitability of a question relating to the letter is such that the group collectively drum-roll the table in anticipatory build-up to me asking about it. “You could take any line of that letter and place it out of context and write an article about it,” Goldsworthy tells me. “If you read the whole letter and have a bit of common sense, it’s obviously not sexist. We wanted to criticise the people that facilitate the sexist attitudes in music, I got really upset when people thought that… Anyone who knows us, knows that it couldn’t be further from the truth. I can understand why people would misinterpret it a little bit, especially if you don’t know us, but they were like vultures, man, and they completely stripped that carcass of meat. They had a good fucking meal on that.”

Thankfully, 2014 has started with a much clearer message from the group, in the form of their eponymous debut LP: a nerve-shredding record most succinctly described at post hardcore, with flashes of The Cure’s ‘Three Imaginary Boy’, The Horrors’ ‘Strange House’ and the dead-eyed punk of Iceage. From the opening guitar maelstrom and seething fury that follows on, it’s a ‘group-of-masked-men-kicking-in-your-front-door kind of a record; one that keeps you as on edge as frequently as it allows you to remain content in the force of its execution. Considering the opening song, ‘Nerve Endings’, was one born out of the nervous energy and anxiety of Mitchell, it sets a perfectly apt precedent for the rest of the record. It’s the kind of guitar album that places as much focus on the grit as it does the sugar and ultimately its success lies in the twitching amalgamations taking place between melody and aggression, between the focused and the unhinged. It’s cloaked so intensely in apprehensive energy and surging, forward propulsion that it makes you want to head-butt a wall and simultaneously try to figure out the atmospheric guitar pitches going on.

Back in 2011 Eagulls released a split 12” with Mazes, on which they covered ‘Mystery’ by Portland punk band Wipers, a group Eagulls seem to share an ethos and mindset with. The brutal, brilliant concoction of gushing energy with a keen focus on tones and textures is only one of the many qualities that made Wipers such a superlative, cult guitar group, but these similar approaches and principles are what also make ‘Eagulls’ such a juggernaut.

As we finish up our second or third beer, we leave Wetherspoons for a wander around Leeds to take some photographs, stealing a stranger’s dog at one point. Walking along the close-to-flooding canal banks, a quiet disdain for the landscape can be sensed and heard from within the band. The skyline is punctuated by looming, shimmering glass buildings; tall, garish, Lego-like blocks of student and young professional flats with the odd remaining old, brick-based building looking more tokenistic by the day. A particular one that Kelly picks out is the old Yorkshire Evening Post building, a sad looking anomaly of a building that, along with the old railways tracks and bridge nearby, is a disappearing aesthetic in the city, drowned out by the shiny and the new. It’s an attitude shared by the group and one that can also be traced to the band’s choice of album artwork (by long time collaborator Andy Jones) – Sheffield’s monolithic ode to Brutalism, Park Hill housing estate. Subject to equal parts derision and veneration, it’s a Grade II listed estate that is undergoing the Urban Splash treatment, transforming the exposed and soot-stained brickwork into a sea of brightly coloured exterior shapes that resembles something from the Early Learning Centre. In the foreground of the shot is a burnt out car the band found there, next to a red telephone box. It’s a snapshot image of modern Britain clinging onto a past with a grip that is ever loosening. It’s a photograph almost too perfect at capturing something large in something so singular, almost looking staged to the cynical eye, but as the band point out “as if we could fucking afford to place and burn a car for a photograph.”

After we walk the streets for an hour or so we retire to a pub called ‘The Red Lion’, a Samuel Smith brewery pub where a pint costs £1.80, the woman behind the bar serves you in her slippers and there is a pub dog happily trotting around the place and falling asleep on feet it doesn’t know. It seems a perfect setting for a group who, it turns out, are not prickly, inherently aggressive or antagonistic – they just have very little time for bullshit or people who deal in it.

They’re the first band that Brooklyn-based label Partisan Records are putting out simultaneous in the US and UK, and having (quite unbelievably) performed on the Late Show With David Letterman in New York last week, they’re keen to point out that they’ve reached this juncture largely by themselves. As Mitchell tells me: “People might look at us now and say ‘oh it’s not do it yourself anymore’ but we’ve been doing it ourselves for four fucking years.”

Indeed, ‘Eagulls’ was made without a deal, recorded at the band’s own pace and generally steering clear of industry convention.

“When we first started playing we would play with loads of bands that would get loads of hype and buzz and then die within a year,” says Ruddel, while Matthews is glad the waiting period is finally over. “I’m keen for it [the album] to be out,” he says, “because shows are different when people know your songs. Like, if I’m seeing my favourite band and they play five new songs in a row, you just can’t get into it as much and that’s essentially what we’ve been doing for the last year: playing an album that nobody has heard”.

“Apparently when Tim from Partisan was talking about signing us he went to some of his mates and said ‘Hey, you heard this band Eagulls?’” says Kelly, “and they were like, ‘yeah, they’re old. They released their single two years ago!’.”

“Record labels want younger people so they can manipulate them,” says Mitchell. “We’re an older band now; we’ve already done all that shit so we know what we’re doing.”

Goldsworthy: “Some of the bands we’ve played with are ridiculous. They can’t even get up in the morning, sometimes they’re pretty much paying someone £30 a day just to get them out of bed”

“Fucking £30?” interjects Kelly, “try £100 plus a day, just to wake them up, get them out of bed and get them to a gig. If you can’t do that yourself, why the fuck are you in a band?”

Talk soon turns to their recent Letterman performance, a wonderful, strange occasion that has no doubt either seen underground bands in the UK swell up with pride or sour with envy. “Considering a lot of our friends are in the hardcore and DIY scene, you might think a lot of people would turn their nose up at that but everyone’s been really proud,” says Goldsworthy. “A bit of piss-taking but everyone seems happy for us.

“I’m really sceptical about stuff because I know how fickle the music industry can be, so I take everything with a pinch of salt. Until the album is out, it’s just a little bubble that PR and press people have created. The real test will be when the album is out, that’s how I judge it.”

“It’s made me really pessimistic,” says Kelly.

“Yeah, like the only way is down!” says Goldsworthy.

Ruddel: “We’ve got a shitload of press since last week, which means you get a lot more people who like you but you also get a lot more people who don’t like you.” Kelly asks if the band read “that” comment on Youtube.

“No, I can’t, man,” says Goldsworthy.

“No, it was class,” laughs Ruddel. “It just said: ‘They sound good. Look shit’. That’s fucking mint, that.”

Ruddel recalls the early aspirations their label had for them. He says: “I think the third time we met [Tim] he spoke about his ambitions for us and things and we were all just sat around having a drink and he said, ‘I’ll get you on Letterman’ and I remember spitting my drink out laughing, being, like, ‘fuck off’ and he was dead straight faced and said, ‘I bet you any money I’ll get you on Letterman!’”

Partisan has quickly become “family”. “The people that work there at the label are the most down-to-earth, real people,” says Mitchell. “The way that they work, they’re just really good.”

“It was really odd the first time I went to their office though,” says an apprehensive Goldsworthy. “I had in my head visions of Nathan Barley shit, people whizzing round on micro-scooters, playing ping-pong and stuff, with it being a record label in Brooklyn, and we walked in and everyone was just working solid.”

Their Letterman appearance was with Bill Murray, and Kelly commemorated the occasion by getting the actor’s name tattooed under his pre-existing Eagulls tattoo (“when he saw it the first thing he did was come up and start kissing it”). If Murray had cancelled for any reason, it would read the name of his replacement – the slightly less impressive Dr Phil.

Of their recent time in New York and on the Letterman set, they all have varying insights. “It was cold,” Mitchell recalls.

“Apparently he doesn’t put the heating on,” says Kelly. “He likes to keep everyone on edge. Or that’s the rumour anyway.”

Goldsworthy says: “It was a rollercoaster. After soundcheck it was like 7 or 8 hours of sitting around asking each other every five minutes if we were nervous…”

“… and that fucking journalist from NME,” says Kelly.

“He was awful,” says Matthews. “He just turned up and said, ‘Can I have a beer? How do you feel the day before doing Letterman?’ The next day: ‘Can I have a cigarette? How do you feel, it’s 10 minutes to doing Letterman? Oh, can I have another beer. How do you feel 10 minutes after Letterman?’ And the next day: ‘How do you feel the day after Letterman?’”

“It’s all he asked,” Mitchell says with irritation.

“I pulled him aside the day before the last day,” says Goldsworthy, “and I said ‘mate, I’m not being a dick, but you haven’t really asked us anything yet, so do you want to think of some questions and we’ll do it tomorrow because you’ve got four pages to fill and you haven’t asked us a fucking thing.’ By the last day I think he knew we hated him as well, so I’m sure that’s going to taint how he writes it.

“I have no idea how or why he’s a journalist. Maybe just for extra money, but even if you’re getting paid, he could have at least done half an hour’s research on the Internet.”

“Fuck him, man,” says Mitchell. “We’ve been talking about him for about twenty minutes.”

“Have we got any photos of him for the article?” Goldsworthy asks.

“Yeah, with a target on his head,” says Mitchell.

We move back to Letterman and particularly the audience.

“They were gutted because they thought The Eagles were playing,” Kelly laughs. “They have a hype man who comes out before the shows and he went, ‘tonight we’ve got Bill Murray’, and the crowd cheers, ‘and we’ve got The Eagles’, and the crowd are going ballistic,” Goldsworthy tells me, with Ruddel laughing and recalling, “If you went on Twitter there were loads of pictures of people in the crowd of David Letterman, taking selfies saying things like ‘I’m seeing the Eagles tonight.’”

The confusion didn’t stop there.

“The day after that, at a gig at (Williamsburg venue) Baby’s All Right, a woman came with her daughter thinking it was an Eagles tribute band. She was trying to get her money back, I think, and it was a mental show as well, people throwing themselves all over and people were pretty wrecked because it was like one in the morning. She was so gutted for her young daughter.”

“Do you want to see behind David Letterman’s desk? It’s a right mess.” Ruddel shows me a painfully normal picture of a rather tatty desk from behind. “It’s a right shit-hole.”

“All the floor and carpets are all scuffed,” says Mitchell.

Matthews: “They had a woman coming round with paint, just filling in the gaps in the displays.

“Personally, it’s never been anything I’ve aspired to do,” he says. “That’s why it was so surreal. You just try your best to play naturally”.

From one anomaly to another, Eagulls find themselves up for an NME Award in the Best Video category (for ‘Nerve Endings’) against some laughably big artists: Arcade Fire, Arctic Monkeys, Haim, Lily Allen and Pharell. But the band are suspect about NME’s intentions. “We’ve basically been told as much that we’ve only been invited to the awards because they think we’re going turn up and get in a fight or cause a scene or something.”

The video for ‘Nerve Endings’ cost approximately £50 to make, but it could have also come at the price of a night in the cells as it saw them briefly risk arrest. They filmed a pig’s brain naturally decomposing, behind which a rather amusing anecdote lies.

Says Goldsworthy: “When I was getting the brain, I was going around Leeds market asking for a pig’s brain and one butcher got really violent and he was like ‘What the fuck do you want a Pig’s Brain for? You sick bastard.’ Because they were selling pig’s heads and I was asking them if they could take the brain out for me and he was like ‘I’m not fucking doing that’ and he was arguing with the other butchers and I went round the rest of the market and nobody else had pigs heads so I had to go back to this butcher. I went back and he started apologising to us but he wouldn’t take the brain out of the head. He gave us a rough guide on how to chisel and pop the brain out. I had a hammer and a knife and did it at home, it was fucking horrible. I popped an eye out. It’s really hard. It took ages. So I prized it open and it was like an avocado, half of the brain was still in.”

“The lads who we record the videos with came round and just started to be sick whilst filming it,” says Mitchell.

Goldsworthy: “We set it all up in the basement anyway and we were starting to worry about it because it had been a week and a half and it still didn’t have maggots. So we were considering cheating and going to get some from a fishing shop.”

“Anyway, we were going to Brighton to play a show,” Ruddel takes over. “I was finishing work at 5 and the van hire place closed at 5.30 so I had to get there in time to pick up the van, but I forgot to bring my license to work with me, so I had to get home to get it and then get to the van hire place in 30 minutes, in rush hour traffic. So, I got a taxi, got home and legged it from the taxi to my house and I was rushing to get my keys in the door and the neighbours all came out, the people from the tyre garage next door and they were like, ‘you’ve had CID and police here kicking your door in, what’s going on?’ And I had ten minutes to get across town, so I was just like, ‘I don’t know mate’, and I ran in, got my licence and ran back out to the taxi and he followed me to the taxi and was like, ‘they’ve been kicking your door down, what are you doing in your basement, you mentalists?!’. And I just jumped in this taxi and sped off, like ‘see you later’.”

“We got back from Brighton a couple of days later anyway and the gas had been cut-off and the locks had been changed,” continues Goldsworthy. “The gas meter for the house was in the basement where we were filming, so the gas man must have come in – as we were having a dispute about who owed who some money at the time – so they came in to switch our gas off and he must have seen this filming and it looked like a kids brain and he must have thought ‘what the fuck is going on?’ so he phoned the police… We got back from a gig and it had just completely disintegrated. It disappeared. We never cleaned it up either. It reeks still but we never got any flies.”

Mitchell: “We did!”

“There’s a bit of footage in the video where you can see the gas man’s boot,” says Ruddel. “It’s either a gas man or a copper.”

Kelly then adds a key point to the rather amusing mishap. “But how the tyre place next door found out about it was because the gas man ran out of the house shouting ‘they’ve got fucking baby’s brains in there!’.”

Whilst the predications of ‘who will be big’ in the next year – along with dull, arguably rigged, polls – continue to shape how we view, and expect to view, the musical year ahead, Eagulls’ bizarre leap into the mainstream eye is one of the wonderful examples of how spontaneity, unpredictability and hard work can still be traits that get you places and consequently re-shape our all-too-often pre-determined musical landscape. They are a group who are used to – and perhaps most comfortable with – playing bring your own booze sweatboxes in the backstreets of Leeds and Sheffield than they are the David Letterman show and this is not likely to change any time soon despite support slots in big venues with the likes of Franz Ferdinand and as they take their raucous debut across the UK, U.S and Europe this year. There is no doubt that Eagulls have arrived in 2014 as some kind of arbitrary underdogs, but the year is theirs for the taking and few could begrudge them smashing it to pieces. After all, how many bands in 2014 do you know that would turn down $20,000 to wear some chinos for a few seconds?