Everything Is Recorded – Richard Russell’s collaborative project exists as part of London’s multicultural heritage

"The city is pretty on fire for new music"

"The city is pretty on fire for new music"

It’s difficult to pin down why Richard Russell is famous. Ask someone who, like him, came of age in the late ’80s and they might remind you that he was one half of Kicks Like A Mule, the rave one-hit wonders whose track ‘The Bouncer’ – with its “your name’s not down, you’re not coming in” catchphrase – crash landed in the top ten in 1992, leaving Russell briefly as one of the poster boys for a scene that was deemed by John Major’s Conservative government as the most dangerous since punk.

Somebody else a little younger might point to his position as head of XL Recordings, which Russell took over in 1993 and transformed from a fairly unremarkable dance label putting out disposable 12-inches with titles like ‘Energy Dawn’ into an admirably broad church that foreshadowed modern-day post-genre musical appetites: under Russell’s stewardship, XL broke acts as diverse as The White Stripes and Dizzee Rascal, MIA and Badly Drawn Boy, Vampire Weekend and Basement Jaxx. It wasn’t all cult favourites, either: after hearing a demo on MySpace in 2006, Russell also had the foresight to phone a then-unknown singer called Adele Adkins. Ten years on, two of the most popular albums of all time have an XL logo on the back.

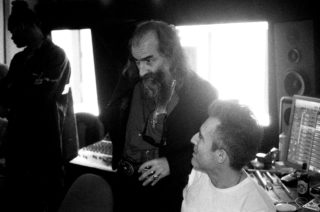

Say the name “Richard Russell” to a certain kind of recent music fan, though, and they won’t tell you about raving or XL Recordings. Instead, they’ll point you toward Russell’s creative rebirth in the past decade, after taking a back seat at the label, as an auteur producer – the sort, like Rick Rubin, Steve Albini or Quincy Jones, whose renown extends beyond the realms of the credit-scouring subscribers to Record Collector. Gil Scott-Heron’s and Bobby Womack’s final albums were made under Russell’s supervision – both of them as much triumphs of man-management as they are artistic expression, and both of them increasingly identified as modern classics – as well as a clutch of debuts from emerging soul and RnB musicians.

Russell has claims to fame, then, even if none of his past lives have thrust him directly into a spotlight. His latest project, though, might alter that. The first album to feature his name on the cover, ‘Everything Is Recorded By Richard Russell’ is a collaborative record born of a series of Friday night jam sessions over three years at his own Copper House studio during which the rule was that, yes, everything was recorded. “There just isn’t anything that can really replicate that process of being together, so I thought, ‘let’s just play’,” he explains, leaning forward on the mid-century leather sofa in his studio’s lounge area. Above the sofa hangs a painting that depicts fabled bluesman Robert Johnson flanked on either side by Kraftwerk founders Florian Schneider and Ralf Hütter, in a neat summary of Russell’s tastes. “It felt like a completely natural thing but people aren’t doing it so much in this era of recording.”

While Russell insists he’s wearing only his most recent musical hat in his capacity as the curator/producer/facilitator/artistic director of ‘Everything Is Recorded’ (“yeah, there you go,” he deflects, when offered a list of job titles he might currently like to pick from), the truth is that the spectres of his previous endeavours nonetheless loom large. For one, this is a record that only someone with a contact list as deep as his could execute: Sampha is the vocal lynchpin, but there are also appearances from Giggs and Wiki as well as newcomers Ibeyi, Obongjayar and Ghostface Killah’s son Infinite, and behind the scenes lurk contributions from titans old and new in the form of Kamasi Washington, Damon Albarn, Mark Ronson, Peter Gabriel and Brian Eno. The sprawling nature of the record’s assembly, too, makes this no territory for a music industry rookie.

For another, there’s also an understanding that while Kicks Like A Mule’s novelty is a lifetime ago for Russell, that generation’s sense of togetherness bleeds through ‘Everything Is Recorded’: although stylistically rather slippery – each of its tracks nods towards a different genre, be it soul, grime, RnB, dancehall or some cocktail thereof – the album retains coherence thanks to an almost familial-feeling thread that’s redolent of the UK soundsystem scene from the turn of the ’90s, the most enduring members of which were The Wild Bunch (who would spawn Massive Attack) and Soul II Soul.

“I think the Soul II Soul and Massive Attack thing is absolutely relevant, yes,” he agrees when asked about the inspiration behind the album. “They were the sound of the record collections of the people who made them, being given equal importance with the new performances by the people who were there in the room. And I think, as much as there is a blueprint to this record, that probably would be it.” Gorgeous album opener ‘Close But Not Quite’, in which Sampha duets with a huge, respectfully unaltered Curtis Mayfield sample, bears out that model perfectly. Centrepiece ‘Mountains of Gold’, too, anchored by Grace Jones’ version of ‘Nightclubbing’ but adorned by a phalanx of rappers, singers and instrumentalists, does likewise.

That said, while the record’s ethos is throwback, Russell is no nostalgist. “I don’t really look at that era with any level of sentimentality,” he admits, of the pre-digital age. “The equipment was clunky, especially for samples, and although I suppose there was something good in that, I really like programming in Logic. Also, I think with the enormous amount of stuff that we recorded, that would’ve been difficult 25 years ago with all the tape that would’ve been involved…”

He drifts into heartfelt considerations of the virtues of old synths versus virtual instruments, but there’s a sense that technological pragmatism wasn’t the only reason that held ‘Everything Is Recorded’ back until now. At one point Russell cites making the Gil Scott-Heron LP in 2010 as “100% a turning point for my life”; at another we discuss the debilitating illness that left him with temporary full-body paralysis in 2013 and bed-bound for a year. And orbiting all this is the Copper House itself, where everything was indeed recorded, and which was only completed after his recovery.

He acknowledges a sense of musical planets aligning. “I couldn’t have made it before now, or I would’ve done,” he says. “It wasn’t made before I made those other records, it wasn’t made before I was ill and it wasn’t made anywhere but here.

“Not just here though,” he says, gesturing up the stairs to the studio’s live room. “It’s a London thing as well, because I think that’s a sound. London just has a history of multiculturalism, musically, making a reinterpretation of things. And you could probably argue it’s a West London thing too – although not necessarily West London as is, but maybe West London as was.”

That distinction feels pointed, especially for someone who’s made his home and career for a quarter-century in Notting Hill. Does the London of 2018, with its vast expense and inequality, and particularly West London, with its helipads and oligarchs, still punch its weight culturally?

He pauses. “Well,” he offers, “this is the only place where J Hus happens,” leaning back as if he’s nonchalantly just played an ace. “That sort of thing’s not happening anywhere else. There’s still life here. I mean, rap music from London is much better than rap music from New York and I never thought I’d find myself saying that. That’s meaningful and exciting.

“In fact,” he adds, ever hopeful, “I think the city is pretty on fire for new music actually – sure, West London is pretty fucked, but London on the whole is pretty on fire.”

Russell’s optimism runs through his patchwork album and beyond. The recent live presentation of ‘Everything Is Recorded’ featured twenty-odd musicians recreating the album’s songs in the round, all playing a game of musical catch with one another as one song unfolded into the next. Russell contributed synth and programming work from a corner of the stage, evidently still not entirely on board with being the star of the show, satisfied instead that the team he’s assembled, fantasy football-style, is more than the sum of its parts.

That role of puppeteer is clearly where Russell gets his kicks now. “Running a label, I’d ended up doing something where I never got my hands dirty anymore, and I ended up without any tools, which I really missed,” he explains. “You just had the phone – you’re there to facilitate other people. I facilitated people to have a lot of freedom to express themselves and to make some really good things, but I needed to extend that courtesy to myself, too.”

Earlier in our conversation, Russell ascribes that managerial-curatorial touch simply to “listening to a lot of music, reading a lot of credits, and being able to interpret who’s doing what and who’s going to get on with who.” It seems that if there’s one thing for which Richard Russell should be famous, in whichever guise, it’s exactly that.