I’ve been Tobias Jesso Jr… Goodnight?

Tobias Jesso Jr. only started singing his own songs because nobody else would. He’s questioning if he really needs to put himself on stage anymore.

Tobias Jesso Jr. only started singing his own songs because nobody else would. He’s questioning if he really needs to put himself on stage anymore.

“I won a raffle one time, and I won a hat. And it was a very expensive, prestigious hat, made by the best hat maker. His name was Gunner Fox, and he made this hat. It was the most expensive thing that I had ever owned and I won it in a raffle between hundreds of people who had paid waaay more money than me for multiple tickets. I paid five dollars for one ticket, I won the hat, he made it custom to me, I wanted it to be huge… so I ask for this hat. It took him a month. He made it out of the finest beaver felt, with a belt wrapped around it. I’m telling you, this hat was maaagic. And a few days later that same hat was stolen off the top of my head, as I was wearing it.”

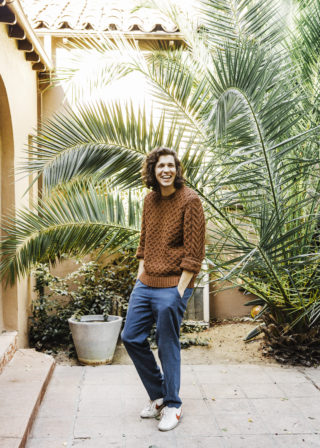

This story sums up Tobias Jesso Jr’s life so far – a guy who attracts the best of luck and the worst of luck, sometimes on consecutive days. On Black Friday 2015, he happens to be on a massive upswing, big enough to carry even him clear of misfortune’s retribution.

Yesterday he bought his first house, in Silver Lake, Los Angeles. If it’s pure coincidence that the same day Adele’s ’25’ became the fastest selling album in US history, it’s a spooky one. Tobias co-wrote its second single, ‘When We Were Young’, and a second track – ‘Lay Me Down’ – that appears on the version of the album sold at American chain store Target.

Contributing to a record that’s sold 6 million times over in seven days has its financial rewards, but for Tobias it’s only half the story, or less. He’s been Adele’s biggest fan since he first heard her music in 2009; right around the time he arrived in LA from Vancouver to make it as a songwriting gun for hire. He failed spectacularly, and after four years of trying (half-arsedly, he admits) he was forced to move back home where he aborted his grand plans and took yet another manual labour job, at his friend’s mom and pop removal company.

By the time he’d taught himself a little piano, recorded some demos just for fun and almost accidentally signed himself a record deal with Matador label True Panther Sounds, Tobias wasted no time name-checking Adele in his very first interview in late 2014. Talking of his derailed Hollywood hustle, he told Pitchfork: “I wanted to be in the studio writing songs for pop artists. I would still love to do that; Adele’s my favourite artist. But that time in L.A. was also like a wake-up call that that’s not going to happen. Everything came down to a point where I was like, ‘I’m not that guy! I’m the guy that makes those guys coffee, and that’s that.’ And my record is about exactly that: Los Angeles and failing and a breakup.”

Today he marvels with the rest of us at ‘25’’s rolling sale statistics that belong to a pre-file-sharing age, only he’s a guy who’s played a part in all of them. He hasn’t been to Target to buy a copy of the version with ‘Lay Me Down’ on it yet, and is worried that he might now struggle to find it in stock. “There was only 1 million made,” he says and pauses. “Imagine that – a run of a million copies being a limited edition!” He laughs his high-pitched laugh in disbelief as we walk back down the hill he lives on in Hollywood.

“My manager made me sit down,” he tells me over lunch at the café on his street. “I’m like: ‘What’s going on?’ I was in the middle of a breakdown at the time, right on the edge. He said: ‘Who would you most like that to work with in the entire world?’ and I couldn’t even fathom Adele, so I was thinking of producers and stuff. As soon as he said Adele, I was like: ‘H-o-l-y shit!’” The blood drains from his face; he freezes; he recreates his widening stare. “From my toes to my head all the happiness was flowing in. It was like winning the lottery or something, and then you start to believe it. And he was like: ‘Yeah, she’s coming to LA and you’re going to get to meet her and go in a room with her and you’re going to do something together.’ I was like a giddy schoolgirl. The happiness was at the top of my head and then the panic started to push it down. So I went to work and I wrote and I wrote and I wrote.

“I spent 10 days writing songs and ideas for her, and the second she walked in the room I forgot every single one. And I was like: ‘Errrr, I don’t know what to say.’ She was like: ‘I’m going to go out and have a fag, do you want to come with me?’ I smoked two packs of cigarettes in four hours that day and I don’t even smoke that much. And then we just talked a lot, and within an hour or so, as we were going through life stories, I’d remember a chord progression, or she’d tell me something and I’d be like: ‘Oh I’ve got something that would really work with that.’ We went back into the room, I sat down and started playing and she sang almost the song that came out. All my friends say, ‘I hear you all over that song,’ but no, the amount of changes we had to do for her that I would not normally do, it’s crazy, and I’m so glad for it.”

Tobias comes alive when he recounts the few days he spent with Adele at his manager’s grandparent’s house. Whenever she left, he and his manager would sit in the room she’d been singing in and relive the day with one another.

“And then Sia dropped by and we did a couple,” he says. “Sia ended up using a couple of [Adele’s] songs, and I was another huge fan of Sia, and when she came in I’d never been so scared. Talk about Adele putting you at ease, Sia was the opposite. It’s like: ‘NO! IT’S THIS CHORD, and it starts HERRRE,” Tobias shrieks a piercing note. “And I saw Adele sat in the back there laughing at the whole scene, because she knew how nervous I was.”

“It was the best, most life-changing experience I’ll ever have,” he says deadly serious, and he’s probably right. “You can’t even put that down to a good year. No, no – meeting Adele and getting to write with Adele is probably the most important thing that’s going to happen in my life.”

Tobias lives on a street in Hollywood that’s appeared in a thousand tourist photographs. It’s the one where the HOLLYWOOD sign is directly in front of you from the moment you turn onto it, despite how long it goes on for. At the end of the day we giggle whilst adding to the problem of people stepping in front of cars to hopelessly attempt to make it look as though they’re pinching or eating the famous landmark. The actual joke is in our purposefully posing way off line, something that Tobias sees on a daily basis and finds great amusement in. His sense of humour is what I like most about him – it’s absurd, and he’s quick to riff off a joke you swing for or any bizarre imagery you throw at him in casual conversation. He’s got an easy laugh and an obsessive and complex imagination, which is best demonstrated during our photo shoot when we become completely sidetracked as he tells us in extreme detail an idea he’s had for a TV show for the past four or five years. It’s called Serious Drama and it might be the best idea for anything that I’ve ever heard – a dark comedy about a misunderstood writer who is molested by Bigfoot at scout camp.

Of course, written down just like that it sounds nothing but gross, but Tobias’ pitch is incredible – for his enthusiasm, conceived gags and plot twists, and the sheer amount of time he’s clearly spent thinking about and developing this one idea that most of us would have entertained and left in the pub. He says it would take him hours to explain the whole thing and I believe him, but for 30 minutes or so he gives it a go, outlining its camera angles, callbacks (Tobias is good at callbacks), character synopsis and even proposed marketing ideas to promote it. It is completely fully formed.

We arrived at this topic because Tobias played a show earlier in the year dressed as Bigfoot, his band in Boy Scout costumes. Talk about forward planning, he did it in order to capture the show for a line in a TV show he hasn’t had commissioned yet.

“I’ve been telling them about Serious Drama,” he tells his manager, Mason, as he steps out of the house to see how we’re getting on.

“Oh wow,” he says. “It’s a journey.”

Mason manages Tobias with his business partner Ben; the three of them live here in the street’s most rustic looking house together with Noah who plays in punk-pop band Partybaby, also represented by the managers. It’s a boys house, from its sofa area and drawn shades at 11am to Ben’s new toy – one of those handless Segway hoverboards that every kid’s going to want this Christmas – which everyone in the house has mastered, and Ben and Tobias jump on and off as they tell me about how Black Friday is America’s most embarrassing day of the year. Ben shows me a video of a grown woman snatching a reduced toy from a four-year old to illustrate the point.

Tobias has a third, day-to-day manager also, which seems a little excessive for an artist so completely solo that he originally toured alone, accompanied only by the piano that overwhelmingly sits at the heart of his songs. When discussing his year, though, it’s apparent just how necessary this team has been to his success, his happiness and ultimately his sanity. “Ben and Mason was the best decision I’ve ever made,” he tells me.

When I arrive at the house in the morning, Tobias is familiar as the person I interviewed at the beginning of the year – a joker with a reason to be happy; a guy who’s making his way in show business after it killed his spirit the first time around. The more we talk, though, the more I realise that the intervening months haven’t been a breeze as they’ve appeared to be. There’s a good chance that he wasn’t as carefree as I thought he was back in January, either.

Momentarily, the joking around on our shoot stops when Brian, our photographer, asks Tobias if he has any shows coming up. He did, but he’s just pulled bookings all over the world, from Europe to Australia. When Brian asks if it’s because he needs a little time to regroup, Tobias says in a solemn tone that appears uncharacteristic: “No, it’s just no life for me. I’d become a parody of myself.”

Today, at least, he has no desire to play his songs in front of an audience again. “I’m not the type of performer I want to be,” he says, before expressing how sorry he is to those fans that have bought tickets to his shows that have been cancelled. He worries when he looks at his phone to see that more shows have been announced as scratched, expecting disappointed fans to be in touch soon. “The worst is when I get an email from someone saying that they’ve booked a trip to come and see me – that’s not good at all. But I also got this email from someone who came to one of my shows saying, ‘hey, I came to the show and was really disappointed by it’ – that’s worse and made me feel terrible.”

There is no ‘official line’ about the dates that have suddenly dropped off the calendar, no ‘exhaustion’ baloney or ‘health issues’ spin, although both are kinda true. He says he’s sat down to try and explain his feelings and decision in a statement more than once, but he can never find the words.

“I was doing more things that I hated than I was doing that I loved,” he explains to me over lunch. “For me, if I had any other job that was like that I would quit. A lot of people don’t understand that, and a lot of people are in jobs that they hate and they feel like I’m copping out – like I’m one of those new kids who can’t handle an honest day’s work, and being on tour is the most dishonest day’s work you can do. I was left with more than a little embarrassment after I played. And it’s not for anything that I would have any control over – it was a feeling inside, like, ‘man, that didn’t make me feel good.’”

Tobias was drinking heavily, but the real problems began when he started playing with a full band – they were too good.

“They could play anything,” he says, “so by the end I was just entertaining myself onstage, which doesn’t do anybody any good. So I’d be like: ‘What do you guys want us to play? We’ll do anything.’ And the audience would be like: ‘Errr, Outkast!’, so we’d play an Outkast song,” he says wearily, “and I’d look up the lyrics on Google.” He looks ashamed when he tells me that he answered his phone to take a call a few times onstage. “That’s a sad, sad story.”

Within a few short months, Tobias’ original concept for his show – the show of a songwriter and his songs, not of a performer and his act – was history. And he’d only started playing live a couple of months before that – just him, his piano and his sweetly imperfect voice.

Having seen him perform twice, each time on his own, it’s only when I search online for his Bigfoot show that I realise just how estranged his live performances had become from those early gigs that so accurately represented his debut album, ‘Goon’. Alone at a piano, there was a learn-as-you-play charm to seeing an artist unsure of himself performing his simple but beautiful songs. His record was venerable and rudimentary, and so too were his live renditions of songs about the time he moved to L.A. and got his heart broken. He played slow because it was the only way he could; he sang like a guy trying because he was. The Bigfoot show isn’t that, and not just because Tobias is dressed as a Sasquatch – it’s a cabaret sound: more professional and slick, but more ordinary also.

More than that, he’d arrived at a point where he was covering other people’s material. This, from a guy who was so desperate to have his music heard he reluctantly decided to sing the songs himself because nobody else would.

“As a songwriter first, I don’t know how to describe it,” he says. “I imagine what I do in a very specific way – songwriting is all I like and all I care about. If I was to describe myself, it would be as a songwriter, there would be no ‘singer’ attached. No ‘singer’ slash…, no nothing; it would just be ‘songwriter’. So I feel that there’s a very specific way to showcase that to the world. It’s definitely an indie thing, it’s not a mainstream thing – it’s for people who appreciate songs, for their structure and their lyrics. And I think that playing solo is the ultimate way to hear a songwriter play.

“I was a big fan of Girls, but I would really, really hold onto a Christopher Owens show, of just him. I got a little lost along the way, and it was like, the shows are going to get bigger, so we need the sound to be bigger… and I was so insecure about playing shows that we added a band.

“It was great for my confidence level, but it lost a bit of that identity. I was like: ‘Wait, now I’m trying to be a singer, because I’m trying to play with a band, and my voice has to be as powerful as this band that’s backing me up’, so the sound has to grow so we need to rearrange the songs, and at that point everything I’ve tried to hang onto as my core, the core is hollow now and I’m trying to be an act.” He sounds exasperated at the explanation, like a man who had stopped respecting his own songs in an attempt to fall in line with how he felt half of the audience were feeling.

Whilst he had been petrified alone onstage, at least he knew that the people in front of him were there for the songs, because there really wasn’t anything else to be there for. Once you’ve got a kick-ass show band, the songs themselves, say Tobias, are buried under a hundred other elements that people can enjoy almost in isolation.

He says it felt like there were those who’d come to hear the songs, and those that were there enjoying the band. “And I guarantee that the people who came to see the band, if they saw me solo they’d be disappointed. I’m not interested in those people because they are not my fans – they are not the people who are interested in what I do and what I’m about. Those are people who just like a sound that comes from a full band – it could be my songs, it could be anybody’s songs, and that’s not as special to me as someone who says, I just like his songs. That’s someone who I want as a fan because that’s someone who I am as a fan.

“There are those people who are just like: ‘Oh, I heard this on the radio…’” he says. “All the power to those people, I love them, but they’re not the kind of people who make me feel good about what I do – they are the people who think I need singing lessons, secretly.”

I ask him if he’s now considering reverting back to his original plan of writing songs for pop stars and retiring from his brief career in front of the music. God knows that the Adele effect would allow it.

“The songwriting thing is something I feel great about,” he says, “and it’s going to be very important to me and my happiness, but there’s a part of me that doesn’t want to give up on the touring just because I didn’t have a good run of it the first time around, because I didn’t write good songs for the first four years of my life. Every time I cancel a show I’m burning a bridge, though, I know that much. But who knows, I’ll give it some time, and it’s better than suffering.”

“Do you know what my ultimate would be?” he says. “That if I had a steady job playing at the same place every week, and people would come down to hear the new songs and be like, ‘I like that one’, or, ‘I don’t like that one so much.’ And at the end of the night you get your 200 bucks for food, and it’s all about the songs.”

“You’ve caught me at a really good time,” say Tobias once our shoot is over. “I met Rick Ruben two days ago and he changed my life.”

He tells me how he drove out to Malibu to meet Ruben at his mythical retreat-come-studio, Shangri-La, suspicious of what all the fuss was about – why did everyone care so much about this producer who can’t even play music himself, or record it, for that matter? How is that producing?

It’s a fair question and Tobias got his answer after a couple of hours spent with Ruben in a white, empty room. “He’s like a life coach, or something,” Tobias buzzes. “He was sat there on the souls of his feet and we just spoke and I told him all about the problems I’ve been having and after a while he didn’t say, ‘oh, just don’t do it then,’ far from it, he said: ‘From what you’re saying, it sounds like you do really want to tour and play shows, but you’re just not happy with how you’re doing that at the moment.’ And that’s exactly it. His whole thing is about working with artists not to say, hey, this would make this song better, but to just ask them, is this song everything you want it to be, artistically? It’s up to you then to say, no, let’s go back to its beginning.”

It’s hook-ups like face time with legendary music gurus – and, more importantly, how they’re handled – that make Tobias’ managers so indispensible. When I ask him how I can get to meet Ruben, Tobias genuinely hasn’t a clue. “These things just tend to happen,” he says, giving full credit to Mason, Ben and third manager Will. “They sorted it out and then explained it to me casually, like, ‘oh, tomorrow we’re just going to drive out to Malibu to see Rick Ruben.’ That way I don’t get overwhelmed,” he says, “because life is constantly overwhelming me.” Similarly, he’s been kept in the dark about just how many phone calls his work with Adele has generated – “They’d keep that a secret because they’ve set my life up so that I won’t have a breakdown.”

Without Ruben’s pep-talk, he admits that he would have wanted to cancel our meeting today, following a year of press interviews that he’s struggled with as much as anything else.

Just as his band were “too good”, so too have his press interviews been too positive about the man behind the sad piano ballads. It sounds like complaining for complaining’s sake, and you’d think that constantly being described as Mr Nice Guy or a hopeless romantic would do wonders for your confidence, but not for Tobias, who loathed the pressure of living up to his happy-guy-singing-sad-songs public persona. Still, I can see how every interviewer that’s met him has come to the same conclusion. I did myself in January, and after larking around with the HOLLYWOOD sign and hearing all about Serious Drama, I still do today. Tobias Jesso Jr. is a nice guy – the kind you want to be friends with – but clearly he’s right when he insists that it’s not the entire story.

“I just feel like I was not meant for an artist career,” he says, plainly. “I know that there are people out there with very private lives as artists who are much more well known than me, like FKA Twigs, who’s known as her artist career, but the difference is that my artist career was me – it was me being me… and getting judged for it.”

I offer him the consolation that he’s at least got his growing pains over within record time – few artists start the year without a debut album and end it a credible Pitchfork darling who’s figured out exactly what he does and doesn’t want to do. He might even be the first to also shoe-in an all-time dream collaboration that could quite possibly set him up for life, creatively, if not financially.

“You say that, but I have a mental breakdown at least once a week,” he only half jokes. “I’m having a good time sat here eating this delicious meal, but put me in a stressful situation I haven’t been in and see how much learning I’ve done then.

“I’m not saying that I’ve suffered more than anyone else this year,” he adds, “and I wouldn’t change any of the bad, because I’ve been given some amazing opportunities. If I wasn’t an artist there’s just no way I would have got to work with Adele.

“The past year has been the year in which I’ve suffered and learned the most, of any year in my life, and also been given the most. I’ve gotten the most, I’ve had the best luck and I’ve also had the worst times of my life.

“Just don’t make me seem ungrateful,” he politely requests of me later, “because I’m really not.”

I don’t think that he is, however complaints of the press being too nice might come across in print. Tobias tells me that his issue with interviews is that they lead to people writing about his character without really knowing him at all, and that includes me, of course. After spending an afternoon with him on his street, and at the risk of adding to the problem, I’d say that the nice-guy-playing-sad-songs thing – the hopeless romantic, jolly giant with a soft heart bit – rings true, and happily so. He shouldn’t feel guilty or ashamed about that. But it isn’t where Tobias Jesso Jr. starts and ends. He is, obsessively, a songwriter, who ultimately wants others to respect the core of popular music as much as he does. The bells and whistles he considered distracting noise, or at least he does when they’ve been hung on him – a guy who always wanted “proper singers” to sing his songs.

He says that he doesn’t know how much real money he stands to make from his work on ‘25’, but he doesn’t think it’ll be enough to retire on like I suggest it might be. That kind of information is how Tobias gets overwhelmed with life, and he’s happy that his managers have kept it to themselves for now.

As for the other collaborations he worked on since ‘When We Were Young’, he’s not sure if he can tell me who they are yet, but on a scale of 1 – 10, 10 being someone of Adele’s caliber and 1 being an artist in the ballpark of Tobias Jesso Jr., he says he’s written for a couple of 4’s and one 9. “And you know that Adele is the only 10, right?”

That puts a negative, it’s-all-downhill-from-here slant on the future, but then Tobias – the raffle winner who never got to fully enjoy his hat – does say to me: “I’ve been on such a gain recently that I think a crash is on its way.”

Maybe’s he’s right – over his accelerated first year and album campaign, maybe he has peaked, so what the hell is he going to do next?

“TV shows,” he says in a flash and with the raise of his eyebrows. If there’s any truth in that, I’ve no doubt that that’s what he’ll do. Things don’t come easily to Tobias, but his has an uncanny knack of getting there in the end.

“I know what a perfect part sounds like,” he says. “I haven’t written a perfect song, to me, and I’m always searching for that. Like, the chorus to [‘Goon’ track] ‘Without You’, that’s like a 95% chorus – I love it. It would love to strive for the 100 (verse) 100 (chorus). It wouldn’t be my voice on it, it would be someone like Adele, if we worked together again.”

“At the beginning of the year, I was eager and I had a lot of ideas about what I could be. I used to say that I always thought of the music industry as one big hotel, and I just wanted one broom closet with a piano to be like, ‘at least it’s my own thing – I’m not trying to rip anyone off, I’m heavily influenced,’” he laughs, “and now I feel like the room is a little bit bigger and it’s still mine, I just need to invite bigger people in there to work with me, and that’s how I can afford it.”