Just imagine… it’s the 1960s where number one singles in the US are songs like ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ by The Beatles – the very essence of sunshine, feel-good pop music, almost throwaway in its fleeting, child-like sentiment. A few years later, things are changing, but not that much, until you go down your local record store and see an album cover with a big banana and Andy Warhol’s name on it, so you give it a whirl out of intrigue. Ten minute’s into that record you are greeted with the demonic, demented screech of viola on ‘Venus In Furs’. For all those years your parents told you that rock’n’roll was the devils music, maybe now you started to believe them. Well, tonight I meet the architect: the devil himself, John Cale.

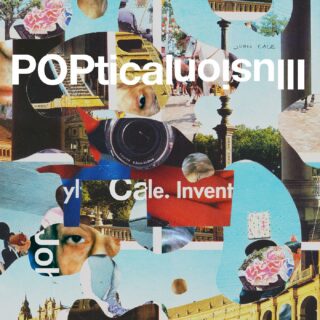

John Cale has recently signed to Domino records subsidiary Double Six Records and is back with a new EP out in August entitled ‘Extra Playful’, which is an apt title, with the record itself being a smorgasbord of sounds, styles and musical endeavours that accesses the many sonic portals and palates within Cale’s brain. An LP will follow around September time with a tour after that. This comes six years after his last record. So, was the break intentional?

“No, no,” he says. “There’s been some things with EMI, and that was like watching a boxing match go sour.”

Oh dear.

“Yeah, I mean, I don’t know, Guy Hands got his hands on it and it just sort of went up in smoke. It’s a shame; there were some very good people at EMI, they took care of me, and I appreciated it. I mean… but look at Domino Records, they could be the next EMI; they have the right attitude towards it, and just look at the music. Although I have to qualify that by saying I don’t want anybody to be the next EMI!”

In his gap John has also been given the prestigious honour of an OBE, which was “totally bizarre. I never expected it,” he says. “I have no idea how it came about. The greatest thing was being there on the day and standing alongside all these people who were receiving the same honour as you are and they’re not there because they are wealthy or famous – some of them are quite poor and they are there because they’ve helped their community a lot. It’s outstanding… that was really inspiring to me.”

Cale has also recently been taking his 1973 seminal album, ‘Paris 1919’, across the globe for the last two years, performing in each city with a brand new orchestra in each one he visits. A pleasant nostalgia trip, one presumes.

“Nostalgia only lasts for a little bit anyway and really it sounds pretty different [to the record],” he ponders. “You’re not doing it to recreate it, you’re breathing new life into the songs.

“That’s a very special kind of show,” he continues. “You can only do that every once in a while, with getting the orchestras and rehearsing and stuff, although they’ll probably continue [once the new record comes out].”

Over the years (almost 45 since The Velvet Underground’s debut) Cale has worked with a huge array of people, as a band member, producer, collaborator and composer. The key to successful collaboration, he says, is “that both parties involved end up going somewhere they didn’t expect to go.”

“You get something out of other people by working with them, and in turn get something out of yourself you wouldn’t have normally done,” he continues. “It’s always a very revealing experience.” He speaks as though he knows the answer to the question, rather than offering an opinion. “If you think you know what you’re doing at any particular moment, if you have that moment with other people you’ll find that you may be wrong,” he says. “They may have one objective idea about what you’re doing and that’s always interesting to see how that develops and comes together.”

That’s quite a trusting attitude to have in regards to other people’s opinion. Surely it could be them who are wrong?

“But the trust isn’t personal, it’s in something creative, somebody else’s vision and it’s really interesting to see and hear other people’s views.”

So does this belief extend to when you are producing records and are essentially the objective voice, not the original founder of the idea or music?

“I mean when you get a band in the studio, quite often they are hearing things completely differently for the first time. They’ve never been on stage and heard themselves so clearly or so manicured, and that can be a daunting experience for a lot of people [when they come in the studio]. When we did Patti (Smith – John produced the seminal ‘Horses’) and the band, they had been playing this stuff on their own guitars and their own guitars where often warped, and when you start to deal with that and hire in equipment, it’s like a baby out of bath water. It took a while to settle that, because they all wanted to play the instruments they played on stage. They worked their butts off to get these guitars that they loved and then you come along in the recording studio and say, ‘Sorry, no. We’re going to be spending more time tuning them than we are recording them.’ So that changes things, because there is a lot of stress on the band, who are trying to make something work that they’ve never thought of before, because they’ve been used to getting whatever they want from their own instruments.”

Largely responsible for shaping the best sounds of the ’70s (Cale also produced The Stooges, The Modern Lovers and Nico), he modestly plays down his role as producer as “evolution”, even if those relentlessly pounding piano keys and sleigh bells that can be heard thrusting their way through ‘I Wanna Be Your Dog’ were at the hands of him, arguably creating the moment punk was born, eight years before 1977. “Well, I mean, I’m telling the truth,” he says. “I didn’t write it. I don’t feel I’m responsible for their output, they are the original owner of that content.”

In terms of his influence, both as a member of The Velvet Underground and as a solo artist, it’s remarkably evident in so many records we hear today, and that has to be strange?

“Yeah,” he says. “I mean, I can understand why they are trying to figure it out because there’s a great deal of disappointment involved in it. You know, we thought [The Velvet Underground] was going to be around for a while and they weren’t. But they’ve really latched onto something – the inability of four people not really being able to agree on anything or much of anything and still produce some music is a puzzle. It’s like that advertisement that slowly shows a glass of water tipping over, it’s the kind of thing that grabs and holds your attention while they tell you what to buy. It’s that same kind of thing, that same disappointment that got everybody hooked on The Velvet Underground, I think.”

So, do people to this day still try and get you guys back together?

“They don’t try, they ask if it’s possible and generally the answer is one big question mark. You couldn’t really do The Velvet Underground anymore without Sterling anyway.”

I ask if the interest is baffling or flattering and John suddenly becomes sombre. His voice drops softly and a sincere degree of emotion coats his every word. “It’s kind of saddening really, it just reminds you of something you can’t do anymore.” A silent pause awkwardly hangs in the air.

“You mean as a collective unit or the inability to write the songs as you once did?” I finally ask.

“Yeah, in regards to without Sterling…we’d always look at each other on stage and hear him peel off a solo, you know? You’d have to wait there for it to unravel. He would unravel a solo and it would take him a while! He would reach these heights, and I was just enthralled. I don’t know how he got it, there was something about him… and something about us in those days.” John sighs. “It just wouldn’t be right to do it.”

So there’s no intrigue there? You wouldn’t want to do it?

“No, not really. I think Lou and I together, unfortunately bring out nothing but the worst in each other. That’s a sad fact of life.”

John’s tone remains undeniably sad through these parts, almost uncomfortably so. I feel awkward in my questioning, as though I’m asking him personal questions about lost family members, when it dawns on me that in many ways I am. Lou Reed, Maureen Tucker and Doug Yule (John’s replacement when he left The Velevet Underground in 1968) all got together for a public convention and interview at the New York public library in 2009. Was this something that John was interested in being a part of?

“Well, it was something that I was not very interested in, but I also sensed it was something other people were not very interested in me having a part of either,” he says. “I didn’t miss it.”

Clearly saddened by the subject matter, I decide to move on before I push my luck or John goes all Lou Reed on me (Lou point blank refuses to talk about anything other than his latest projects when giving an interview. Sometimes even a mere mention of The Velvet Underground or details of his past is enough to make him walk out of a room).

John’s previous collaborations are plentiful and duly noted but is there anyone he would still love to work with? Immediately the tone picks up.

“I don’t know, I think a lot of the people I’m already fascinated with are already doing it [by themselves]. I mean Eminem is really outrageous, he’s so strong, and Snoop, I always get a giggle out of Snoop. There’s this other guy who works with Snoop called Kokane and he’s outrageous – he’s got this voice, it’s very much like Sly Stone; it can be very deep and soulful one minute and then very high and beautiful and romantic the next. The range he’s got is really excellent. But he’s already doing it. Lupe Fiasco I like a lot too.”

Slightly dumfounded, I was expecting to hear a list of strange avant-garde composers, but instead it turns out John Cale gets a kick out of Snoop Dogg. But, then, knowing the strong focus on lyrical content Cale applies to his own work, it’s hardly surprising that he feels attached to the lyrically superior genre of hip-hop.

“Yes, absolutely,” he agrees. “Some of the lyrics are extreme. I mean, Eminem, I can’t believe that guy can stay angry for so long, but he does it really elegantly”

Angry lyrics elegantly constructed? Sounds familiar, so I ask something I never in a million years thought I would ask John Cale: is he familiar with Odd Future?

“Odd future? That name rings a bell.”

The full title is Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All.

“Hum,” he quips with genuine thought. “Are they the rap outfit that were at Coachella?” Quite possibly, I respond (they were).

“I think there’s about seven or eight of them and they make videos?”

That’s them, yes.

“It’s a shame I missed them. I was out of town. But I’ve read about them, it sounds fascinating. When I read about it I thought, ‘Hum, how do you keep something like that together? So many people doing so many different things.’”

I explain the age group of the outfit – some are teenagers and that the oldest member is 23.

“Wow! There’s hope for us yet man! Really, I mean it. What’s their website?”

So as I instruct John Cale on where to look for Odd future, I query the latter part – is originality something that he still considers or thinks about when writing and making music?

“I’m careful, in that I don’t listen to the radio. I only listen to things I like. I guess make it personal. If you make it personal then it’s yours, you know? I mean it’s really about working out your own thoughts as you go along and only you can do that, so it’s your own business.”

John was on The Culture Show in 2009 being interviewed by Miranda Sawyer when he had one of his moments of complete sincerity and honesty that I too have experienced whilst speaking with him. It’s difficult to convey in print, but on multiple occasions he will slow down, and very softly and thoughtfully respond to something with such a gentleness but complete conviction that it’s very difficult not to be humbled by such emotion, honesty and insight. One such moment came when he told Sawyer, “I have ambition…ambition to fulfil my full potential, which I don’t know if I have yet.” It was a remarkably vulnerable moment, one that opened up a whole world of questions by turning the key of self-doubt, but it was met with childish giggles from Sawyer and an inability to follow up the question because it was “very serious”. The interview terminated at its most vital point. After two frustrated years, I follow it up. Is this really how he feels? John Cale, founder of The Velvet Underground, pioneer producer, the original creator of one of the world’s greatest and most popular cover songs (‘Hallelujah’), OBE, nearly twenty solo albums made, collaborations with Eno and Nick Drake amongst many others, film composer, festival curator and still recording at nearly 70 years old – this man really feels he hasn’t reached his full potential? “Yes,” he says. “I still haven’t found the perfect topic to take control of, the perfect balance of music and words. This is something I’m still looking for.”

Is this something that you have never found, or that you have but are looking to better? “Yeah, to better it I guess. Not in terms of competitiveness. I take lessons from other people; I don’t try and imitate them as I think that would be the kiss of death, but I take lessons from them.”

What John clearly likes to absorb he is capable of imparting too, and he has provided many lessons whilst speaking to him, the main one being that he likes “surprise endings”, and it’s clear that the end is not in sight yet.