JPEGMAFIA – The possibilities are infinite

The Baltimore rapper is making political music – but recent LP All My Heroes Are Cornballs is also a free-wheeling expression of human acceptance and how flawed our heroes really are

The Baltimore rapper is making political music – but recent LP All My Heroes Are Cornballs is also a free-wheeling expression of human acceptance and how flawed our heroes really are

It’s hot in Baltimore – early September, and still thirty degrees outside. It is so humid that, at lunch, a waiter comes over to tell me it’s too warm to eat on the patio – he’s sweating just serving me; he says I’m going to need to sit with everyone else in the air conditioned restaurant, away from the dangerous heat. Despite the weather, JPEGMAFIA, the rapper I’m here to interview, arrives wearing a sweatshirt. It hangs loose around his wiry frame, over shorts. He has gold earrings in each ear – the one on the right moves gently as he speaks, catching the light. JPEG, or Peggy, as everyone calls him, has this look in his eye that reminds me of bars from that old track ‘Return of the Drifter’, by the British rapper Jehst. It goes: ‘Soldiers hold a cold stare like they’ve never been scared/ but live life like they know their time’s precious and scarce’.

Peggy’s ex-military, so maybe that’s how he’s perfected the soldier stare. His eyes are amber-brown, intense and alert, if slightly glassy from weed smoke – he is watching, taking everything in, holding the world at a distance as he looks you in the eye, the way soldiers have to in order to conceal their vulnerability. He is not fucking around – although I don’t mean to suggest that Peggy is aggressive: it’s fearlessness is all. He is serious about this stuff. “The only thing I want people to take from me,” he says, “is, like, don’t expect anything else other than hard work. Don’t expect it to sound or be about something, because I could talk about anything at any point.”

It’s hot in the 8×10 too – the club on the city’s East Cross street, where JPEG is performing to launch the release of his latest album All My Heroes Are Cornballs, supported by his Baltimore friends and peers (Butch Dawson, Abdu Ali, Ghostie). People are queuing around the block a couple of hours before it starts – testimony to the rapper’s growing popularity here, following the success of his 2018 album Veteran. Certainly, there’s a sense of something more intimate than your usual relationship between an artist and his fans in the exchange between Peg and the crowd waiting outside. A young guy at the front of the line has come all the way from Richmond, Virginia, to see this, he tells me, and he’s excited, travelling alone – his friends are going to catch the livestream back home. So far, so normal. But later, as the queue grows and Peggy runs a sound-check, there is some trouble in the street – a drunk or drugged up guy is threatening fans in the queue. The boy from Virginia knocks on the window of the closed club for help, and Peg leaves his sound-check to see what’s happening, not bothering to wait for security to arrive. He eyes the drunk guy with that soldier-stare, steps forward and talks in a low voice: precise, but unconfrontational, as his management look on uncomfortably – starting something with the crowd would not be an ideal way to launch this album. Eventually, the drunk guy nods at whatever Peggy is saying and stumbles away.

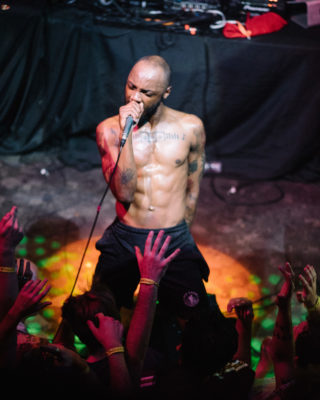

On stage Peg is frenetic, vulnerable and sexy. There’s nothing of the veteran now, other than his lean physique – topless and slick with sweat, hunched over himself as he delivers his lyrics to the mic, his voice occasionally breaking into a register somewhere between a wail and scream. All My Heroes Are Cornballs contemplates the state of the world in fractured, gender-bending tracks that veer between desperate and nostalgic. “I can’t feel my face, oh god!” he cries, on ‘Jesus Forgive Me, I am a Thot’, and then, “Show me how to keep my pussy closed”. The track ‘BasicBitchTearGas’ is an auto-tuned cover of TLC’s ‘No Scrubs’ – another track is called simply ‘Kenan vs Kel’. If Veteran was a straight up political statement, there’s something more irreverent about Cornballs – it’s a strange and playful riff on popular culture, composed as a kind of improvisation in the wake of Veteran’s success.

“When Veteran was released I knew I didn’t want the next thing to sound like Veteran,” Peggy says, “but I didn’t really care what that meant. I guess the only thing I was thinking was, like, I want it to be more me, and more like I’m not just laser focussed on political topics or anything. I’m just talking in general and if they pop up they pop up – and they still do. I guess the difference is I’m just letting the songs form themselves rather than trying to form something around them.”

On the Veteran tour, Peggy kept working on new music: producing more than ninety instrumentals (at one point he scrolls through his phone, showing me the long list of unused beats he made while working on Cornballs), which he returned to months later when he was ready to write lyrics for the new album. “And I did that on purpose – because I wanted it to be like I was two different people. So I made the music, stepped back and listened to it again after not listening for a while, so it was fresh, new. So it was good to work through because it was two genuine things, happening at the same time, smooshing them together or something like that.”

The politics of Cornballs might be more irreverent than its predecessor, but as Peggy says, a politics is still present – how could it not be, in these end times? At first though, when I ask about the intentions of the work, Peg brushes my questions off lightly, as if he hasn’t really considered the deeper meanings at play. “So my titles for songs are usually kind of whatever,” he says, when I ask the (admittedly unoriginal) question about how he names his tracks. “Unless I want it to be some specific thing, like ‘Kenan vs Kel’ I named it that on purpose, but sometimes I name something something just because I don’t have a name for it. Like ‘Jesus Forgive me I’m a Thot’, I didn’t have a name so I just named it that.”

It soon becomes clear, though, that Peggy doesn’t really do anything without thinking about it. The ‘thot’ in the title is a provocation, as much as anything. “To draw out stupid people, because you know niggas who be like, ‘I’m not gonna listen to that, it has the word thot in it’, I’m just gonna save them some time, like let’s not waste each other’s time.”

As for the album title, “I’m very specific about [that]. This title means – it just sums up how I feel about the state of celebrity I guess. In an era where all of your skeletons are out the closet and people nit pick specific things. It’s just an era where you can’t hide anymore. You can’t be like a douchebag or a rapist, and just exposing the fact that lots of people we thought were really great are just doing the same bad shit normal people are. Because they’re just normal niggas. So All my Heroes are Cornballs is just a blanket statement about we’re all human, or something like that.

“You can still have heroes,” Peggy explains, leaning forward to emphasise his point. “You just need to accept the reality of the situation. Because things aren’t that black and white. Because there’s no all good person, you know what I mean? You can still have role models, I have role models, but you just have to accept. That’s what All My Heroes Are Cornballs is about. Acceptance. We might not want to think it’s this way; we might want to think people are all good or all bad, but really people are just a mix of both. Sometimes leaning one way or the other, but usually not…”

Given the crowd that gathers for his launch, and the fans who recognise him in the Baltimore streets as we shoot the cover photos, I wonder whether Peg feels any sense of extra responsibility now he is on the cusp of fame. Is he more careful about his behaviour when there might be consequences beyond his own reputation – now that he’s an influencer of sorts?

“I think it’s impossible not to feel some kind of responsibility, at least subconsciously. But whether or not I’ll act on that – I don’t really feel obligated to do anything for anybody. I have my morals and I stick by them, so that’s really it for me. I’ve been making music for so long, and no one cared until, like, last year. So for me all these niggas are new. I don’t feel no type of way about being myself because I really believe that’s what got me here.”

He takes a sip of water.

“All the issues that people are talking about on Twitter, I was rapping about them in 2015, because I gave a shit. And I didn’t make that up to make myself look better or anything. It is what it is, I stick to myself. It seems that at least social media caught up to what I think rather than me trying to catch up to them, so whatever. I feel some kind of responsibility, but, like, I’m gonna stick to my moral code. So I’ll stick to that – and you can accept that there’s gonna be something you don’t agree with me about at some point. But maybe you’ll agree with me about everything. Who knows? As long as I’m not doing some kind of crazy shit.”

Back at the album launch Peggy jumps into the crowd so that he is right at the centre of the teeming mass I’m viewing from my position on the balcony above the stage. The skin from his torso is hot against the skin of his fans. At different points during the set the audience get on stage to jump out and be held up by one another. There’s this intoxicating sense of connection moving around the club, drawing us together, boundaries dissolving; the body of the crowd becoming part of JPEG’s own body. It’s fair to say I’m finding it… affecting.

“That’s just Baltimore,” Peg tells me backstage when I ask him whether his gigs are usually this intense. And maybe he’s right – it’s a city known for its raw intensity, The Wire, Serial, all that investigative reporting at the Baltimore Sun (admittedly I’m not sure where Hairspray, Baltimore’s other iconic cultural product, fits into this analogy, but you get my point). That’s why he chose this city as the place to launch the album. Although he was raised in New York – relocating to Atlanta just before he became a teenager – Peggy feels a profound connection with Baltimore. He moved here in 2014, after a four-year career in the US military. Very soon after his arrival, the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray at the hands of the Baltimore City Police led to uprisings across the city. The defiance of citizens in the face of state violence had a profound effect on Peg, who released his first project as JPEGMAFIA, 2015’s Darksin Manson, as a response to Baltimore’s resistance in the wake of Gray’s killing. Although he is based in LA now, his affiliation with the city and its citizens endures. And the racial politics that have inflected Peggy’s work to date simmer under the tracks on the new album too.

I notice it in his use of the word ‘cracker’ – a class-inflected racial slur for white people, related to the ‘white trash’ concept that marginalises America’s white poor. Peggy uses ‘cracker’ repeatedly on this album (and on previous records), and I wonder how he squares the class and race aspects of that. It isn’t that I personally find the word cracker offensive (I’m white, but it isn’t used in the UK, where anyway the relationship between race and class is quite different to the US), it’s more that the mash up between that word and ‘nigga’, which he also uses, seems to signal some sort of class solidarity – as well as directly acknowledging the racism that is endemic in US culture.

“It’s actually really interesting you bring it up. Because, like, yeah the word cracker does have a class aspect to it because when other white people use that word, or when they used to, they were talking about lower class white people. So it’s like their n-word in a way. It’s funny because with white people it has this context of like, ‘you’re lower’, but its just because, like, I dunno, because cracker for black people it has a positive context, at least for white people, because it’s supposed to come from like cracking the whip or something. But yeah I put words like that there on purpose because they’re meaningless, ultimately.”

He clearly doesn’t think words are meaningless though. It’s that flippancy again – his habit of initially dismissing what it turns out is actually a conscious politics. “People listen to people like me, talking about other people that look like me all the time. But as soon as that gun is being pointed at a cracker – and what I mean is as soon as that same antagonistic viewpoint is pointed back at them – they don’t know what to do with it. But yet they listen to other people do it all the time. It forces them to think about the idea that they looking at this shit like some zoo shit or something. Because its like, ‘why you upset I’m saying shit like cracker, but you listen to x amount of niggas talking about they killed x amount of niggas all the time, with no thought process?’ You don’t think about it at all. Niggas be arguing whether they can rap the lyrics. ‘Can I say the n-word with this?’, you know? I like using those words, the reason I put those words in there is to force stupid people to reveal themselves. Because someone who’s smart and racist will not react – but someone who’s a dumbass will see and have an immediate stupid reaction, because that’s all they can do, you know what I mean? Yes, I said cracker specifically so you could do this, and you’re doing it. You did what I wanted you to do. It’s supposed to draw those people out, because these kind of people are liars. So if I put that kind of language in there it forces them to reveal who they really are, which they wouldn’t have otherwise. They would just wrap it up in some bullshit. ‘Oh I’m not racist, I love black people, I have a black dog’, or some shit. But its just if someone has a problem with me saying cracker – you can guess the rest.”

He shrugs. “Sometimes I use the word cracker with that connotation, like I’m a white person using it to talk to someone lower class, because it has double the disrespect. They don’t feel like I should be saying that anyway, so for me to be masking myself as someone better than them – stupid people do not know how to react to something like that. It’s too thought out and drawn out, and they only can react stupidly to it.”

Peggy’s use of language is also something of a reckoning with the inherent classism and racism of military life that he’s left behind, about which he has no nostalgia.

“Anything in the US is going to be mostly white males, because that’s the majority of the population. So the military in the US is mostly white, some black, some Hispanic. There’s nothing surprising, there’s nobody interesting, there’s nothing interesting going on in the military other than what you think is going on. So for me I just don’t like the culture around it. The bro-y kinda like frat boy culture. I can never exist in spaces like that. The people are too stupid for me, they’re not – it’s not saying I’m smart, but these people are like the lowest common denominator of people that you find.”

Like many US military recruits – and like many UK recruits too – Peggy enlisted because, as a poor kid in the city, he had few other options. The military on both sides of the Atlantic recruit poor kids the way drug dealers do – turning up where they know vulnerable children hang out, offering a salary, adventure, the possibility of strong father figures and a way out of poverty. (And the military recruiters are just as cynical as the drug dealers too: a friend who worked in advertising once told me how officers would refer to these type of recruits – poor, inner city, few other options – as ‘cannon fodder’ during client meetings where they designed recruitment campaigns.)

“They have a target audience,” Peggy says. “They know that option is not enticing to private school kids, because they have options. Children like me didn’t have options. So this was one of the ways I saw to make a living for myself. When I was in the military there were different types of people – the people who joined because they genuinely want to defend their country and they loved it, there’s people who are just crazy and want to kill different races, and there are people who just cannot function in society and are skating by in life, and they are just there. And that makes up the majority of them.

“I didn’t have any fucking money. I’m not like these trust fund niggas; they get into the rap game and they parents be paying them and shit. I didn’t have any help so that was the only option. You know, when you’re poor recruiters come down there to where you’re at and they present you with the option. I had no money for college, no prospects – no nothing. I just wanted to make music. But I wasn’t even thinking about it for music. I was just thinking ‘I should do something with my life’, ‘cause, either [join the military] or I’m just gonna be dead.”

Music had long been a calming influence for Peg, and his expression through hip hop was a means of channelling his rage both before he joined the military and after he left. “I been making music since I was fourteen. When I was in [the military] I had already been like five, six years deep. I just been making music for a while. I always had an interest in it, because, I dunno, just something about it made me feel calm or some shit. It still does. So I just always liked it. So one day when I was 18 I just realised, yeah I think I like this, I wanna do this. I don’t really like anything else, this is what I enjoy doing.”

He tells me how experiments with noise especially inspired him in the early years. He’s especially fond of UK grime – of the way grime artists play with sound to upend the listener’s understanding of the world. “Odd sounds, sounds that you don’t find in things normally. But making them make sense. I love that about grime and like, fucking – the beats, like the old, old grime beats, it’s like the craziest shit, like what the fuck is going on here? I love it.”

And you can tell he does, because there is this sudden joy in his voice and his gestures when we’re talking about grime; a tangible pleasure in the possibilities of noise. “They like, they take sounds that are really whacky and strange and they make them rhythmic,” he says. “It’s interesting, taking something that’s unappealing and just forcing it to be something that people like. It’s fire, yo! It’s so beautiful man. This is the basis of why I love making music. The possibilities are infinite. I have, like, a weird bath of sounds,” he turns to his manager, “is that a word man, like bath of sounds? – Like a plethora of sounds, I like to texture things. I enjoy it, man. It’s like making a cake or something.”

Still, if his own music has become known for its experiments with noise, then Cornballs, he hopes, offers something of an antidote to that. This is a new flavour – softer maybe, at least more carefully woven. This new direction is most clearly realised on the track ‘Free the Frail’, a collaboration with the vocalist Helena Deland that peters into a beautiful, watery close. The lyrics for the hook that Deland improvised during a recording session were moved to the end of the track to achieve this cascading, waterfall effect.

“Nah, she’s a genius,” Peg says, when I ask him about working with Deland. “I contacted her because I think she’s an excellent songwriter, and the way she structures music is just wild. Like she just – I don’t understand how she writes. The way she writes is just like a rapper or something like that. And I wanted to harness that energy on the album, and I just thought that song was the best fit. She, like, hummed a little bit on it, and I was waiting for her to do something, like she was gonna add some words, she was gonna flesh it out, but then we decided it sounded good as is. Then she added that thing at the end where she did it a cappella. She did actually put those words to [the hook] at first, but I decided it [worked better] as a standalone thing because you can hear all the intricacies.”

This texture, these intricacies, are maybe not what his existing fans expect, but they mark the place where Peggy is at now. He has, maybe, processed some of the trauma of living in a culture of racism – at least, he’s able to command the expression of that trauma in his music more keenly than in the past.

“I think people have, like, an idea of me,” he says. “But before, the difference is that I wanted to put this rage out, because that’s what I felt at the time. This was fresh when Michael Brown happened [18 year old Brown, an African American teenager, was shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014]. I had a lot of rage and shit and that was the energy I wanted to put out. And now, I still feel that rage, I’m just able to control it and go into it when I need to rather than letting it consume me. I couldn’t do anything but what I was doing when it was coming out. But now I’m able to control it more. Like, now I’m able to show more variety because I’m in a better headspace, as opposed to just broke and depressed and angry. So like yeah, I wasn’t thinking logically at the time is the difference.”