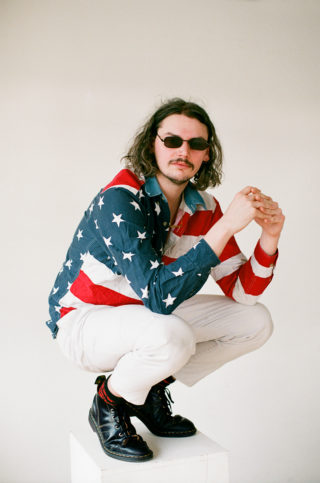

Lazarus Kane – The American Dream is alive in Streatham

Interstate highways, brown suits and the age of narcissism

Interstate highways, brown suits and the age of narcissism

Huddled in the booth of some seedy looking pub not far down the road from tonight’s scheduled show, I’ve barely sat down with our drinks before Lazarus Kane takes his chance to exhibit his new kimono. “This one’s custom made,” he says with a grin stretched wide across his face. “I decided to get brown on brown because it’s the colour people find most ugly. I thought why not get something to compliment my face.” The embroidered paisley is only partially visible behind its matching silk brown liner. Much like his adorning garment, Kane blends in seamlessly to our skewed and haphazard surroundings.

A self-proclaimed ‘anglophile’ and a proud graduate of Speedy Wunderground’s class of ’19, he’s known respectably by fans across social media as ‘Mr. Kane’. Though his mannerly reputation precedes him, he sits slumped across the velvet sofa, dimly recounting his all-American upbringing. “I grew up in a time where you had to call your father ‘sir’. Because of that, I like to think there’s a few artefacts of formality left in my approach to things.” Born in Arizona and raised into a religious travelling community, Kane spent the majority of his formative years travelling up and down interstate highways. Speaking hurriedly in his thick cowboy twang, he makes no secret of his attempts to escape the subject. Adding with a grim expression, he says, “it’s a period of my life that I tend not to look back on too fondly.”

Opting out of his contract with God and deciding to redirect his faith into making music, he spent years circuiting small-town venues, playing to practically any passing trucker or hillbilly who’d listen. “Back then, it was just me. I didn’t have the whole ensemble,” he explains. “I used to get really nervous performing too. I had a whole bunch of cassettes tapes that I used to listen to just to calm myself down.” Having suffered decades of limited success, it wasn’t until his triumphant arrival in Britain and an encounter with Speedy Wunderground poster boys Squid that his current project, Lazarus Kane, was born.

“It sometimes feels like the line-up changes every week,” he says outlining his band’s ever-revolving door policy. “When we’re playing shows, I spend half the time just making sure everyone’s in the building. I’ve always loved bands with members constantly coming in and out. We’re a bit like that. Sometimes there might be six of us, sometimes there might be ten.” He’s not joking either. Counting his current line up across his fingers, he struggles to recall the name of his new guitarist. Tonight will be his first show.

It’s this mantra of manic spontaneity that Kane cites as the driving force behind his creative process. “Your first idea is usually the best idea. You should never dampen that initial spark,” he says with a sudden air of assertion. “Some musicians spend months in the studio trying to come up with some mega hit, but I think it’s more interesting to keep hold of the imperfections and natural blemishes in creativity.” Just listen to the pelvic-pounding punch of his sleazy disco debut track ‘Narcissus’. A bold statement protesting our dystopian, self-obsessed reality, it’s exposé of commonplace vanity serves up a deeply unsettling blueprint.

“Times are weird. People take themselves so seriously,” he says wearing a bleak expression. “When I was growing up, celebrities belonged in the movies and on the cover of magazines. You look around now and that could be anyone. But what people fail to understand is they’re actually just the small version of that. It all equates to just a completely meaningless existence.” With an unmistakeable bitterness, he continues: “People don’t care as much about their fellow person anymore. On ‘Narcissus’ I was trying to highlight the hypocrisy. Everyone’s pretending to be so self-righteous all the time when the truth is, nobody really gives a damn. No one is holier than the first line of that song.” Narrating the track’s leading statement, he recites: “Kindness isn’t simply a test. This isn’t some kind of dick swinging contest.” In just a few utterances of explicitly detailed satire, it paints an ugly portrait, and one that’s all too difficult to avert your eyes from.

We spend our lives relentlessly preaching to one another, each of us armed with a manifesto of so-called wholesome and virtuous beliefs. But remove the platform to showboat and does anyone actually care? Kane doesn’t seem to think so and continues to rattle off excerpts from his poignantly directed commentary: “I know your flaws and I know your faults. Alcohol intake and righteous retorts.” Never before has compassion felt so oddly transparent. “Writing that song was a really cathartic experience for me,” he says. “I wanted to get out all my frustrations and that’s what it’s really about. But really, we’re all the same. We’re all narcissists, it’s a fundamental human flaw.”

As we each pause to ponder our own deeply fabricated existence, our moods begin to reconcile as is he averts the conversation towards his budding relationship with none other than Mr Speedy Wunderground himself. “You only need to look at his work. The guy’s a genius, a fucking genius.” He’s of course talking about Dan Carey; the enigmatic producer who’s prolific and pioneering record label has birthed some of last year’s most exciting and influential new artists. Having first heard Squid’s name through feverish word of mouth, Kane recounts how a meeting with the band’s drummer and vocalist Ollie Judge helped steer him in Carey’s direction. “When I first heard ‘Bmbmbm’ by Black Midi, I knew he was the guy I needed to record with.”

With the original demo clocking in at just three and a half minutes, Kane laid out his specifications for ‘Narcissus’ upon the first time he went meet Carey in his South London studio. “I wanted it to be the most rhythmic thing you could imagine. I didn’t want to use live drums, I wanted it all to be drum machine. I wanted it to feel like it had grabbed you and was shaking you by the collar.” Succeeding to secure Carey’s undivided attention, he ordered Kane to assemble a band and promptly set about getting to work. Caught up in the furore of his own nervous excitement, he recalls, “I got really fucking drunk the night before recording. Dan had told me that I needed to be in Streatham for 9am the next day. By the time I woke up, I was feeling fucking dreadful.”

Bleary eyed and barely conscious, “Dan told us to unpack and set up our equipment. All the while he’s placing these huge guitar amps side by side around the room. There must’ve been about fourteen of them.” Still sweating out the remnants of the previous night’s session, Kane set out an agreement with Carey. “I hadn’t told the others, but I’d asked Dan to get it all in one take.” Now beating his hands together to accentuate his point, he explains, “that’s the way I like to work. The immediacy is very important to me. I want everything to be kept as spontaneous as possible.” The band played for fifteen minutes straight and Kane describes the manic scene of tangled guitar wires, straining amps and a frenetic energy connecting each individual band member. “Dan told us it was very important to only stop playing when he said so. Every time I looked up from what I was doing, he was running around adjusting things like a lunatic.” Pausing briefly to consider his next words, Kane says, “it was literally straight out of something you dream about. It was this completely unique, immersive and all-encompassing thing. It was a performance. All of it captured.”

It’s clear the experience has imprinted a lasting effect on Kane, yet upon enquiring whether he’d work with Carey again, he seems regretfully uncertain. Appearing to sit and deliberate, he’s curious about his own interpretation of what truly makes up the age-old American Dream. Lightly chuckling, he defines it to me. “Back home, folks really buy into the idea of the so-called ‘dream’. It’s what keeps people going, even in their darkest hours. But in a weird sort of twist, I’ve found mine over here instead.”

It’s a warming sentiment of achievement, and even more so from someone who’d spent so long a criminally unsung voice for the masses. If I took away anything from meeting Kane, it was his innate unpredictability as an artist and whether or not he himself knew what was truly instore next.