Maple Glider: “When I’m not playing shows, I’m in bed by 9pm”

When Tori Zietsch goes into town from rural Australia, she becomes someone else

When Tori Zietsch goes into town from rural Australia, she becomes someone else

“I have a sensitive energy. I’m conscious of how much I’m out in the world because I’m really affected by it. I need time alone.”

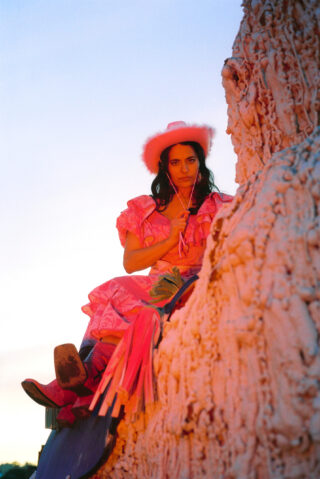

Maple Glider is the sonic pseudonym of Australian born musician and singer Tori Zietsch. When referring to her performative double, admittedly in a surprisingly detached way, Zietsh laughs as she says: “I swear to God that lady has too many outfits.” She playfully represents a fascinating dualism which most of us embody, a kind of split characterisation between, on the one hand, our flamboyant ambitious selves, and on the other, our gentle sheltered introversions. The trouble for most of us is that we can’t choose which side will present itself throughout the week. Not the case for Zietsch, who splits her time between smalltown café work and farming, having recently moved to a very rural part of Australia. She says: “I need nature, space and quiet. When I’m not playing shows, I’m in bed by 9pm!” On the weekend, she heads into the city as a totally different person, equipped only with a suitcase full of whacky outfits and a fake microphone, which is in fact a large pink dildo. She giddily admits: “I could not keep up with Maple Glider full time, that’s for sure. It’s a form of expression.”

Zietsch is on the cusp of releasing her second full length record, I Get Into Trouble, a softly spoken, gorgeously eloquent battle against childhood indoctrination and adulthood relational trauma. The title refers to a bible story based on a condemned, sexually assaulted girl named Dinah, who is also the protagonist to one of Maple Glider’s singles from the record. “I’ve really struggled to reflect on my own experiences with the church as a kid, having those ideas ingrained into me at such a young age. It’s been painful.”

One of the principle aims of the album is to acknowledge childhood trauma which many of us store in the attics of our minds, subsequently affecting us in adulthood. This is a collection of courageous and matter-of-fact songs that eschew the possibility for Zietsch to hide behind anything at all, aside from her cunning accomplice, Maple Glider. However, she admits that she “certainly didn’t feel confident” when she went into record the album, although she did have a strong intention to reveal even the most personal parts of herself in it. “I had this dragging feeling that these songs, which were so personal to me, and had been difficult to share with anyone, needed to come out and be let go of,” she says. “To some degree releasing these songs has allowed me to move past them mentally and emotionally.” A kind of songwriter’s therapy perhaps.

I’m surprised when she tells me that writing about her issues through song is easier than expressing herself in conversation. It became clear throughout our conversation that Zietsch is perhaps warmer and easier to engage with than she gives herself credit for, which only adds to her charm, not just as a person but also as a performer also. She tells me: “Songs are a great vessel for moving through feelings. Once a track is concluded I feel a great sense of empowerment as opposed to the vulnerability I experience before I’ve made sense of the song’s issue in my head. It’s so cathartic to have positive feelings come out of what ultimately started as an intensely dark, emotional place.”

Many of the tracks on I Get Into Trouble are addressed to unnamed individuals, and I was curious to ask whether Zietsch would like for those particular people to hear her. “Some yes, some definitely no!” she says. “I wrote two songs for my brother, which I showed to him. The others are tricky. I have a lot of fear attached to letting my actual thoughts be heard by some people. I’d like for them to hear them but wouldn’t want to know how they’d react.”

Many of the tracks on I Get Into Trouble are addressed to unnamed individuals, and I was curious to ask whether Zietsch would like for those particular people to hear her. “Some yes, some definitely no!” she says. “I wrote two songs for my brother, which I showed to him. The others are tricky. I have a lot of fear attached to letting my actual thoughts be heard by some people. I’d like for them to hear them but wouldn’t want to know how they’d react.”

With that, it occurs to me that what is so refreshing about Maple Glider is that there is nothing egocentric at the crux of this character. Ultimately, these songs are for everyone; they exist without a refined, single target. They are beautiful precisely because of their relatability to all.