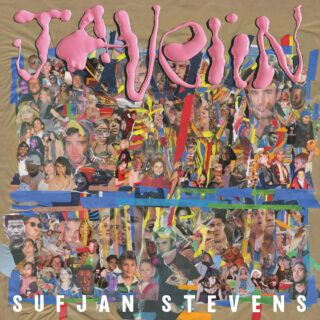

Sufjan Stevens

Javelin

9/10

9/10

Any attempt to determine what an album is ‘about’ risks overlooking a skilled songwriter’s ability to fuse fact and fiction and obfuscate the origins of their inspiration. This is certainly the case for Sufjan Stevens, who has often preferred to maintain a safe distance from the stereotypical singer-songwriter’s transparent first-person confessionals.

Although the lyrics of Javelin hardly read like naked diary entries, it’s difficult to overlook the undisguised references to a disintegrating relationship in many of the uniformly powerful songs that populate Stevens’ first album in full singer-songwriter mode in eight years (accompanied by a 48-page booklet of art and essays).

Glimpses of hopeful beginnings and spiritual questing (notably on the positively hymnal ‘Everything That Rises’) crop up, alongside a general feeling of taking stock. There is also a cover of Neil Young’s ‘There’s a World’ that transforms the original’s portentous arrangement into a weightless glide full of bright and unadorned beauty. However, there is a sharp twang of lived reality in the weary and wounded manner in which Stevens sighs, “I was the man still in love with you / When I already knew it was done” on first single ‘So You Are Tired’ (a heartbreakingly lived-in lament for the left behind, mapping the acceptance stage of the end of a relationship with a grace that makes most attempts to chart a break-up in song seem hopelessly banal and clunky). The bitter recriminations and, ultimately, some semblance of uneasy peace (“Our romantic second chance is dead / I buried it with the hatchet / Quit your antics”) that sweep through the stunning eight-minute centrepiece ‘Shit Talk’ (a refreshingly blunt-speaking title for a hugely ambitious, triumphant mini-epic), meanwhile, feel startlingly intimate and undisguised.

‘Will Anybody Ever Love Me?’ marks a stellar return to the rousing choral singalongs of 2005’s Illinois, but the mood has turned from a communal celebration to bruised self-reflection: despite the massed voices pushing the tune to ever more ecstatic heights, this is essentially the sound of the singer gazing into the darkness, alone and in need. On the stunning title track, the protagonist imagines what might have occurred as the consequence of a sudden – and unintended – destructive act: little more than Stevens’ fingerpicked guitar and featherweight voice, the simultaneously delicate and resilient song (which nods towards the deceptive simplicity of prime Simon & Garfunkel) manages to sound like a timeless standard while also feeling deeply personal.

Javelin is far more compelling and complex than a standard-issue my-baby-left-me dispatch of minor-key woe. Imagine the conflicting emotions that ricochet all across the emotional spectrum (not to mention the skillfully applied blend of plain-speaking confessionals and poetically obscured introspection) of Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks. Mix with the acrobatically versatile arrangements of peak-era Brian Wilson constructing opulent homespun symphonies in the solitude of his bedroom. Add a huge dollop of stirringly pretty if not downright heavenly melodies (without the desperate-to-please vacuousness that usually accompanies unashamedly forthright campaigns of ear-pleasing: these are without fail tunes of real substance and bite), and you’re not far off the bruised beauty and exquisite sadness of Javelin.

The record Javelin feels most closely related to is one of Stevens’ own, Carrie and Lowell. That 2015 album distilled impossibly painful subject material (bereavement and the memories of an unconventional upbringing that grief had brought back to the surface) into a sparse masterpiece. On Carrie and Lowell, the songs were often directed at an elusive parent who had to leave before questions had been answered. Many songs on Javelin also find the protagonist left alone, reflecting on the past, taking stock and wondering – worrying? – about the future.

It’s perhaps fitting that Stevens has realised songs this brazenly personal largely on his own: Javelin evidences his Prince-like ability to write, arrange, play, produce and record tracks that resemble the opulent outpourings of a tightly drilled studio crew almost entirely solo, with just a few guests. The songs here often start from a point of quiet contemplation, with just Stevens’ piano or softly plucked acoustic guitar and hushed vocals, before additional elements – including percussion, subtle electronics, wind instruments and multilayered backing vocals – enter the frame to craft elaborate orchestrations. Especially on initial listens, there are times on Javelin when the application of arrangement touches can feel like a superfluous distraction from the unadorned beauty of the songs, almost as if Stevens doesn’t always completely believe in the peerless potency of the indestructible melodies he’s crafted for Javelin. That said, the extra touches (especially the massed backing vocals) can also elevate the melodies to an ever-brighter sparkle: the simple xylophone melody on the lullaby-esque ‘My Red Little Fox’ accentuates the song’s stately melody to such levels of indelible perfection that it’s easy to imagine the melody lying in hibernation underground for eons, just waiting for the right songwriter to come and excavate it.

Javelin provides irrefutable proof that for all of his wild stylistic leaps and gifts for elaborate grand gestures, Sufjan Stevens’ most remarkable talents lay in emotionally resonant songwriting that really does not require many extra trimmings or gimmicks to move the listener to the core.