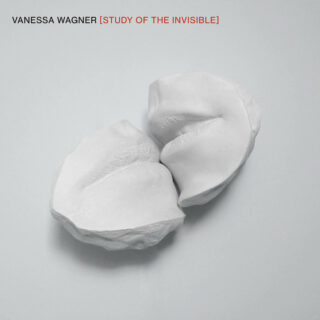

Vanessa Wagner

Study of the Invisible

(Infiné)

7/10

(Infiné)

7/10

Curatorial auteurism has been an important part of classical music’s tradition, with a canon of composers and pieces slowly being created over time by those with the influence to control their exposure. Vanessa Wagner, hailed as “the most delightfully singular pianist of her generation” by Le Monde, is interested in establishing a new, modernist canon of writers that understand the merits of true minimalism and the serene clarity that unfussy themes can elucidate. With her new album, Study of the Invisible, she brings together fifteen pieces by composers from the last half-century, many of them rare or even unpublished works.

Wagner is able to translate her rich and deeply felt playing style to the full gamut of composers and pieces selected here, from the elegant patience and growing wonder of Brian and Roger Eno’s ‘Celeste’ to the skipping, palpitating heartbeat of David Lang’s ‘Spartan Arcs’, the rush of which at times is a thrill and at others feels like it could spill over into panic.

She nearly draws a whole symphony out of the most streamlined of compositions on Philip Glass’ ‘Etude no. 16’, Wagner’s surges and withdrawals of feverish expression drawing the listener into the deep waters with her, while she keeps us buoyant with the tease of sweet melodies. Her technical dexterity is never in doubt, but when Bryce Dessner’s ‘Lullaby (Song for Octave)’ moves from single lines of melody to entire flurries of deceptively complex notation, you barely notice the transition.

We hear sonic onomatopoeia in both her rendition of Suzanne Ciani’s ‘Rain’ and in the ringing and clanging of Julia Wolfe’s ‘Earring’, as Wagner hammers the tightest of high notes, while on Harold Budd’s ‘La Casa Bruja’, low-end reverberations allow for the gradual nature of the piece’s progression. Wagner conveys the pregnancy of each moment, asking listeners how it feels to be forced to pause one’s life for a minute and embrace the altered states that repetition can access.

Do not mistake minimalism for simplicity; what elevates Wagner’s playing here is not the dizzying blur of her fingers or any reinvention of form, but the character that she imbues into these pieces. There is great skill in inhabiting other people’s compositions this personally, with the emotional expression of internal character somehow having to translate into something audible. When every motion is felt intently and every decision is made with a profound understanding of the material, like it is across Study of the Invisible, then you are knocking on the door of transcendence.