Keep the car running: the story of Fat Possum Records and ex-military, ex-con bestselling author Nico Walker

How an obscure blues label ended up publishing the explosive literary debut by an Iraq vet and serial bank robber

How an obscure blues label ended up publishing the explosive literary debut by an Iraq vet and serial bank robber

It was a balmy April day with scattered clouds in the sky as people went about their Saturday morning business in Lyndhurst, a small suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. As it was getting closer to lunchtime and people started to head out to diners, cafes and restaurants, a young man walked into a bank wearing sunglasses and a hoodie. The pregnant bank teller didn’t notice him initially as she was busy serving another customer.

Walking towards the teller window he shoved aside the customer, quickly flashing the gun he was carrying. “You know what this is,” he said plainly, as she handed him over $7,000, which he then stuffed into a white plastic bag and swiftly walked out.

Driving away from the bank, he changed clothes and hats behind the wheel, as a carrier bag full of cash sat on the passenger seat next to his gun. A wail of sirens blared out and so he sped up. Weaving in and out of lanes with his foot pressed hard on the gas, soon the sirens subsided to a quiet whir, before they disappeared altogether. There was a momentary moment of peace. Then the car hit traffic. The sirens became louder again, intensifying, getting closer. Panicked, he began to drive through the traffic, bumping and scratching cars in the process, before swerving into oncoming traffic. The police continued to make ground as multiple car sirens joined into a shrill chorus. They followed the car as it hurtled through a Burger King parking lot before crashing off into an embankment. Before he knew it, the 25-year-old Iraq veteran – and recipient of seven medals and commendations – was surrounded by screaming police with their guns drawn. This was Nico Walker’s 11th bank robbery in four months – but it was to be his final one, as he was soon sentenced to 11 years in the Federal Correctional Institution in Ashland, Kentucky.

Walker wasn’t your archetypal person to sign up to the army as a “grunt”. He came from a stable middle class family and when studying at college, aged 19, he decided suddenly to drop out and enlist. He was colour blind and so became a medic who went on over 250 combat missions in Iraq. Many of these would be responding to improvised explosive devices, which may result in working on badly injured bodies from the bomb blasts. Or in many cases, simply zipping up his friends into body bags who were dead upon arrival.

When returning in 2006, he struggled to adjust to civilian life. He couldn’t sleep due to anxiety and when he did images of death and horror would play on an endless loop. He tried booze to numb it and help him sleep but the nightmares persisted. So he tried oxycontin. His mental health, undiagnosed PTSD and anxiety disorders continued to worsen. Intravenous use of oxycontin turned into heroin use and soon enough he was robbing banks to feed his addiction. Walker’s story has recently been adapted and dramatised for the film Cherry, starring Tom Holland and directed by industry titans the Russo Brothers. The film is based on his semi-autobiographical novel of the same name, which he wrote on a typewriter while he was in prison.

However, one aspect to this story that tends to get glossed over in the film world, or in broader media coverage, is the unique musical link. Days after Walker’s book came out, he was offered $1m for the rights to adapt it, although this book may never have come together at all if it wasn’t for the input of the man behind Fat Possum records: Matthew Johnson. It’s also a record label that celebrates its 30-year anniversary this year, and one that is no stranger to working with unique characters with jagged backstories.

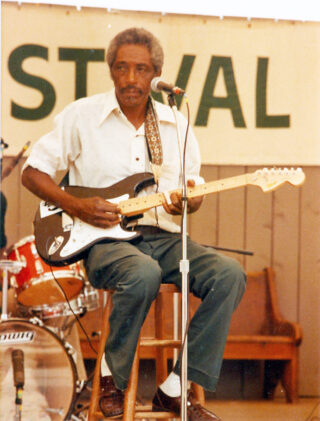

Fat Possum started in 1991 and initially specialised in discovering blues players from the North Mississippi region, many of whom had never recorded before. Acts such as R. L. Burnside, Junior Kimbrough, T-Model Ford and Cedell Davis were all revered locally and stars of the juke joints around the area, but many had never played beyond these rambunctious makeshift venues, or had any desire to. The acts had not just lived lives worthy of singing the blues – many of them had the kind of experiences that were the very blueprint for the genre.

Growing up in 1940s Chicago, Burnside lost his father, two brothers and two uncles all within 12 months. All were murdered. Years later Burnside himself was convicted of murdering a man over a craps game. Ford too was sentenced to a chain gang as a young man for murder. Davis experienced severe polio as a child, resulting in very little hand function, but he managed to utilise a butter knife to create a distinct and singular style of playing. All of which he did from a wheelchair for the majority of his life, because during a police raid at a club he was playing in 1957, he was almost trampled to death in the ensuing stampede, with both his legs broken in the process.

Is it fair to say, then, that label founder Johnson is attracted to rough-around-the-edges underdog characters. “Yeah, I think we all are,” he says. “They are definitely more interesting because they’re not overexposed.”

Fat Possum has changed somewhat since its early days. “It’s not a blues label anymore,” says Johnson, who has released work by Iggy Pop, Dinosaur Jr, Townes Van Zandt, The Black Keys and Al Green. “There used to be a gazillion older guys and they’re all gone now. It’s not the same. Those were the last people who grew up in the ’50s. We had this one guy, Charles Caldwell, he was like the last blues guy I messed with. He was great, really charismatic and everything, but as soon as we signed him he got pancreatic cancer, obviously brought on by a lot of drinking. I got tired of it. Everyone was ragged out from 60 years of really hard partying and on their last legs. It was soon the case that everyone who was really inspiring was gone. Signing The Black Keys set us on our course to become what we are today.”

Johnson notes that communication with artists has become a little easier than it was back in the early days. “Not only was this pre-internet but a lot of these people didn’t even have phones,” he says. “It would sometimes take a day to get in contact with someone. R. L. used to hang out at a pool hall, so we’d leave messages for him there. It was a hell of a lot of driving around.” The artists weren’t always the most straightforward to work with either, with many being suspicious of motives. “Everyone was, like, ‘Well, I guess you got these guys to trust you…’ I was, like, ‘Hell no!’ You can’t undo a lifetime’s experience of getting fucked over by white people in one deal. R. L. and those guys couldn’t understand why somebody wouldn’t rip somebody off if they could. They certainly would. They assumed I was fucking them over, and honestly, in a way I think it’s probably not a bad way to approach the record industry.”

Johnson also co-runs Tyrant books, and after reading a BuzzFeed profile on Walker back in 2013, he got in touch. “I was a history major and I’ve always been fascinated by bank robberies,” he says. “There’s always been a spike in robberies after wars in America. Once these kids go and see all this horror in the Civil War they weren’t content to go work in a general store or hang out on the farm for the rest of their lives. Some guy is now totally qualified for somebody throwing grenades at him for the rest of his life – how do you come back from that? When I read that BuzzFeed piece and he was picking up the fucking pieces of his buddy and his gloves were melting touching his burning skin, it was like, how fucking harrowing. Bank robbery compared to that place is like going to the fucking dry cleaners. Who the hell in their right mind wouldn’t become addicted to heroin after that?”

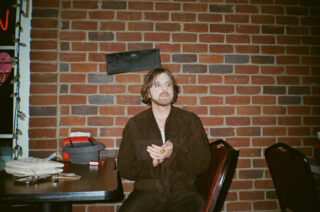

“He approached me very cautiously,” Walker recalls, now released and living in Oxford, Mississippi with his new wife, the poet Rachel Rabbit White. “He wrote a letter and I didn’t know who he was or any of the things he’d done. I just thought I was getting a letter from a guy. He mentioned he had a record label and I presumed if he’s taking the time to talk to me it would be a pretty small little mom-and-pop operation. I’m not a snob so if somebody gives me the time of day, I’ve enough respect to write them back.”

It soon transpired that the BuzzFeed article was in the process of being turned into a screenplay by the journalist who wrote it. “I was like, ‘Man, I don’t give a shit what you do but if you don’t fucking get ahead of this story other people are going to tell it for you,’” recalls Johnson. “You’re going to live in the shadow of it and you’ll be that fucking guy at the bar trying to tell a story nobody believes. Get in front of this or you’re going to just be a fucking casualty of it.”

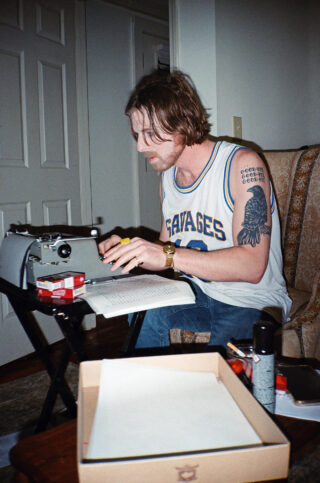

“It’s embarrassing but I used to mess with poems,” Walker tells me. “I didn’t have anything in prison so the only thing I could do for Christmas was make a piece of artwork, a poem. There were a couple poems I sent and Matthew saw something in one. He said I should write a book and I really didn’t want to but he’s a pretty persuasive guy. He made a good point that I had nothing else to do so I might as well give it a crack.”

However, it was not the most auspicious of starts. “The first thing he sent was so fucking bad,” laughs Johnson. “I was like, ‘Oh my god, what have I encouraged?’ I was yelling at him: ‘Goddamnit, write it like you would say it!’ He had only read books from the 1800s – he had never read any modern fiction – so it was like this Victorian shit. It was just horrible. But then he finally learned how to write in the voice he talked in.”

Walker echoes this trajectory. “When I started, I sucked,” he says. “I think I had one more chance left and I sent him something and, for whatever reason, he saw something in it that made him breathe a sigh of relief and that maybe this whole thing wasn’t a terrible mistake.”

Johnson: “I called him and I was like, ‘All right, everything you sent me for the last three or four years is fucking horrible, but this is good. Go from here.’ And then he wrote the entire thing in like a fucking weekend.”

The book was a success, charting highly on the New York Times bestseller list and earning rave reviews that positioned it as the great novel of the opioid epidemic. The day after Walker was released from custody lockdown started. “Which was kind of ironic,” he says. “But you make do. I’m used to dealing with bullshit so this is kind of par for the course.” Walker has been at best apathetic about the film, choosing to distance himself from it – including refusing a role of executive producer – and at the time of publishing he has not even seen it. “It wasn’t me in the book so I’m not sure it will get much more accurate in the film,” he says. “It’s a weird feeling. It is literally like the equivalent of just being replaced by a more charismatic, more attractive, vastly more popular version of yourself.”

I ask him if the prison, book, film, interview cycle going over his life repeatedly has allowed for deep reflection? “I’ve done a lot of fucked up shit,” he says. “I’ve done a lot of stuff I regret. I certainly regret joining the fucking military. It’s just about the most bullshit thing in the world. I went with good intentions, I just wanted to help people. Then when I went to prison it was a bit of a shock when you first get there, but you can only be shocked for so long. You accept things pretty quickly and you adjust.” There have been some positives to jail, Walker feels. “The good thing about prison is that I’d be fucking dead if I hadn’t gone there,” he says. “I really don’t have a shadow of a doubt in my mind that I would not be alive right now.”

It was also the place where he started studying and becoming obsessed with language, while reading much more. “Before prison I wouldn’t read books or anything like that,” he says. “I just used to shoot dope and sit in front of one of the eight channels I had to choose from until four o’clock in the morning. It’s pretty fucking lame. I’m still an asshole but I was a real asshole back then. If I hadn’t gone to prison – well, I’d be dead – but up until the time that I died, I’d have been this horrible fucking asshole. I think the most embarrassing thing about going to prison was that for somebody like me who had advantages, I was 25 years old and I didn’t know a fucking thing. I realised I was completely fucking ignorant. So it was like: I may as well try and learn some shit. That’s how I did it, I was just so fucking embarrassed by how goddamn ignorant I was.”

So, is Walker and the story of his life being turned into a film by the biggest film directors in the world bizarrely part of a lineage linked to obscure bluesmen from decades ago?

“I think we’re both people who get frustrated with pretension,” Walker says of Johnson and what he sees in him. “It’s underrepresented in literature and it’s like the way he approached music, bringing people in who were not very glitzy. They weren’t glamorous, you couldn’t use them to sell clothes, and they had that sort of almost proletarian attitude that is very challenging. I guess he likes that kinda shit.” And for Johnson, does he see a link between the work and character of his old blues renegades and his contemporary literary one? “God knows what happens when you die,” he says, “but if there’s a card game or decent bar up there I would assume that Nico and R. L. and some of the other people would be getting along real well.”