Cate Le Bon: the grief is in the saxophones

Swinging between 'oh fuck' and 'fuck it', before settling in Joshua Tree as the world turns upside down

Swinging between 'oh fuck' and 'fuck it', before settling in Joshua Tree as the world turns upside down

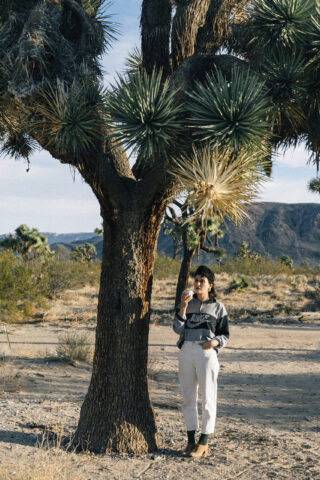

Cate Le Bon bought a house last year. Since moving to Los Angeles in 2013, she’d slowly become enamoured with Joshua Tree, making the six-hour round trip more and more often; to get away from the city for the weekend, to visit her close friend, Warpaint drummer Stella Mozgawa, and, towards the tail end of making her last album, to get it finished, renting a place for a month and holing up with collaborator and co-producer Samur Khouja. “That’s when I really fell in love with it,” she explains. “With how it felt to be out here. It’s insanely beautiful; like an alien landscape, but there’s a softness to its beauty. It’s gentle; it doesn’t feel at all oppressive. The days are so long, and the sky is so big. Any time I was ever here, it would break my heart to leave.”

If you can’t quite see Le Bon, a deeply thoughtful crafter of nuanced, intelligent art pop, in surrounds that, to music fans, are most often associated with the arena bombast of U2 and the snarling machismo of Queens of the Stone Age, then you’d be in the same position as her new neighbours were for the past 18 months. She and her partner closed on the property in February 2020, as coronavirus was beginning its slow creep from east to west, from the lower echelons of the news cycle to the headlines. Le Bon left Joshua Tree, with Khouja, for about as dramatically different an environment as you could imagine, short perhaps of the moon: Reykjavík, where she’d be spending five weeks with her friend John Grant, producing his new album (June’s Boy from Michigan). Then, as her diary had it, she’d head back across the pond for a tour with Kurt Vile, on which they’d play separate sets but share the same backing band.

We all know what happened next. Le Bon’s stay in Iceland ultimately lasted three months. “I don’t think you could ask for a better place to be in those circumstances, honestly,” she says over Zoom from Joshua Tree, where she is now, finally, permanently ensconced. “A really civilised island in the middle of nowhere, cut off from everything. But it was still terrifying; the Foreign Office urging Britons to come home, and America shutting its borders. Stella arrived on the Tuesday to record drums for John’s album, and at five o’clock the next morning, I was rushing her to the airport so she could get on the last flight to Australia.”

Best-laid plans went up in smoke, as it became increasingly clear that Le Bon would not be writing her sixth album in any of the exotic, far-flung locations she’d shortlisted; not in Chile, or in Norway. She couldn’t even get back to California, which both disrupted Grant’s record – the finishing touches to which were supposed to be applied north of San Francisco – and eliminated her new home as a potential base for album six. When some British restrictions were lifted in the summer of 2020, she returned to her old hometown of Cardiff, where she spent a purgatorial period entering into a cycle of having her hopes raised then dashed, of the U.S. border reopening. “Eventually, I knew I had to bite the bullet. I couldn’t bank on getting back to America. I flew Samur to Cardiff in January of this year, built a studio, knuckled down, and got to work.”

Accordingly, Le Bon’s sumptuous sixth record, Pompeii – one swathed in grandeur, from the historical resonance of its title to its songs’ recurring religious imagery – was conceived not in an environment befitting its ambition but, instead, in a child’s bedroom in a terraced house that Le Bon once lived in, fifteen years ago – “the total opposite of what I’d wanted.” She’d craved isolation, but not this kind of isolation – she’d hoped to be secluded, whereas lockdown felt more like being stifled.

“It was extreme,” she says, “marinating day after day in a tiny little room, and the only thing you have control over is what you’re making. Outside of that, you’re going through the same mental polarisation as everyone else. One minute there’s hope, the next there’s existential dread, and you can’t help but wonder if this is the last thing you’re ever going to make – and if it is, will anybody hear it, anyway? We might all be dead. You’re swinging between ‘oh, fuck’ and ‘fuck it.’ Confronting time for everybody, wasn’t it?”

Eventually, routine emerged. She had her most potent weapon in hand: Khouja, who speaks her musical language like nobody else. In the room next door, focusing on his painting, was another close collaborator, Tim Presley, with whom Le Bon released two albums as the duo DRINKS. The three of them would walk down the street for coffee each morning (“our commute”), then back to the house for eggs before retreating to their studios, often for more than twelve hours at a time. Like most of Le Bon’s work, Pompeii shifts shape constantly over the course of its nine tracks, but it feels like a counterpoint to Reward, too. Where that album was an exercise in airy exploration, Pompeii is grounded by a deep sense of groove, a product of Le Bon writing it largely on the bass guitar. “It was a foundation for everything else to interlock around. There’s something meditative about the repetitive nature of bass riffs, and so the genesis of the whole record was my love for playing bass.”

It is the bedrock around which the rest of Pompeii is built, and a consistent sonic palette gradually reveals itself. Woozy synths and softly fizzing guitars characterise the likes of ‘French Boys’ and ‘Cry Me Old Trouble’, while saxophones are woven into the fabric of ‘Dirt on the Bed’ and ‘Running Away’. Mozgawa, meanwhile, took her reputation as one of indie rock’s most reliable beat-keepers to a new level by providing Pompeii’s percussion from over 10,000 miles away, in what proved a bittersweet contribution for Le Bon. “We had an app that let us all work together at the same time, on four different screens, with the sessions starting at 10pm UK time,” she explains. “It was kind of amazing; everything was happening in real time, so you could say, ‘keep it tight here, maybe don’t play that fill there.’ It was almost scary how functional it was, but it was sad, too, because one of my favourite things is to be in the room when Stella’s playing, and it’s quite a cold process doing it remotely. There isn’t really the room for the normal chat and conversation you’d have.”

The logistics of making a record in the circumstances are one thing (solutions can be sought, whether technological or, in the case of some of the auxiliary instrumentation, practical, with social distancing allowing for the saxophones to be cut at a Cardiff studio), but the emotional tenor of the songs is another matter entirely. And whilst Le Bon’s cramped home studio might not have readily lent itself to sweeping, evocative lyricism, the broader situation and its implications changed the way that she wrote. “There were a lot of different things at play,” she reflects. “I think escapism is definitely appealing to the quarantined mind. Being in a situation where there’s hope in some moments and a fatalistic outlook in others, I think it probably draws different moods and ways of working out of you, without you really realising.”

As she ruminated on how quickly her old life had crumbled under the sudden, unforeseen pressures of the pandemic, the lure of Pompeii as an appropriate metaphor under which to group these songs became increasingly obvious to her. “It felt like the perfect setting for everything that was going on, thematically. There’s a global crisis happening, but you’re locked down in an empty room, and all the exits feel as if they’re sealed. I couldn’t help but think about existence, and the futility of it. Resignation, really.”

Le Bon is not religious, but she began to realise that her negative emotional response to her circumstances was coming to mirror those generally associated with faith – Pompeii is laced with references to guilt and original sin. “I was wondering about how culpable we all might be, in one way or another, for what was going on, and for me, that smacked of collective guilt, the sort that religion imposes on people. The guilt we were feeling, the sacrifices we were making, they felt like the same sort of things that are touchstones of faith, and I ended up kicking out against that. It’s not meant to be declarative; it’s more of an exploration of my own feelings, as I was trying to find something to hold on to.”

“The grief is in the saxophones,” Le Bon pithily put it in a short blurb on the record that she sent over along with it. It is also, though, in the album’s words, in the manner in which she had to shuffle the lyrical pack, as she found that notebooks full of ideas had suddenly ceased to resonate. “It wasn’t that I wanted to speak directly to the times,” she says, “and already I’m getting the sense that nobody wants to talk about everything that’s happened; people are sick of it, and that’s understandable. I think writing for the album became its own kind of escapism – almost like a version of Dadaism. It was quite a complicated process, finding words that felt like they spoke to me in the moment, and in the end, I had to trust that maybe if I don’t fully understand the songs now, that I was just writing a letter to my future self instead.”

Hanging over Le Bon in a more literal sense, meanwhile, was the image that has made it, in a revised form, onto the cover of Pompeii: a painting by Presley that casts her as a nun, that became an important visual inspiration as the record came together. “There was something very magnetic about it. It sounds slightly ridiculous now, but this portrait had a real power over us – Samur was taken by it in the same way, and it had this massive presence in the room, as if it was helping us choose the right synth part, or whatever. It was like it was a visual representation of the palette we were going for.

“When the time came to figure out the artwork, I knew it had to be that, but I also felt like it would cheapen it or something, to have it reproduced so many times. So we sort of recreated it in photo form. I think it was supposed to be me, at least. Tim always says that when I tell him I like a painting. It’s interesting, though; you’re not always aware of what’s permeating you, what’s driving you. It seemed like more of a mystery than ever this time around.”

With the record finished and the world beginning to open up again, Cate Le Bon is now back in Joshua Tree, ten minutes down the road from Mozgawa’s place. She’s continuing to produce for other artists – as we speak, she’s in the thick of working on Devendra Banhart’s latest. Between her own songs and her appetite for collaboration, her work is as multifaceted as it’s ever been, and her enforced absence from the road has been a reminder not only that touring is only one part of her musical life, but that music itself is just one aspect of a wider creative whole. “The most I’ve ever enjoyed music is when I was in furniture school,” she explains, referencing a year-long stint learning to craft tables, cabinets and chairs in the Lake District in 2017, ahead of the writing of Reward. “It takes the onus off of it, the intensity out of just doing one thing. Since then, I’m always trying to strike that balance with something else, some other project, because it’s a very beneficial thing. I’m always searching.”