Jimothy Lacoste preaches the positives of aspiration, acceptance and convincing the world that he’s a spoilt rich kid

A shopping trip to the high-end stores of Bond Street can turn preconceptions on their head

A shopping trip to the high-end stores of Bond Street can turn preconceptions on their head

At Burberry’s New Bond Street store, the stairs leading to the menswear department are lined with immaculate, heavy pile carpet in a fantastically impractical shade of cream. Sleek, Art Deco-style banisters guide the way to tastefully-lit chambers on the lower ground floor, its walls sparsely lined with clothing rails and covered in staff-sanctioned customer graffiti. Shop assistants glide around the space silently, smoothing shirts and straightening rows of signature trench coats, which currently retail at £1,495 apiece.

Jimothy Lacoste is stood examining the shoes. In his hands is a fawn-coloured loafer, decorated in Burberry’s trademark tartan, edged with navy blue, calf leather piping and embellished with a buffed gold chain. “Classic. The more simple, the better,” he nods approvingly, turning it over to inspect the sole. “£450. The perfect price.”

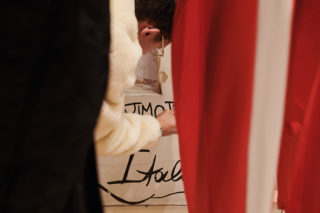

As we prepare to exit, Jimothy chooses a black marker pen from a selection on a ledge, crouches and carefully adds “Jimothy” to the lower regions of the wall in capital letters, the tail of the Y spiralling inwards like the shell of a cartoon snail.

As predicted on 2017’s breakout track ‘Getting Busy’, life has suddenly gotten quite exciting for Jimothy, real name Timothy Gonzales. Following a steady string of standalone tracks with enjoyably low-budget music videos, the Camden-raised rapper is now signed to Black Butter Records, the home of Rudimental, J Hus and Octavian.

His first release for the label was September’s single ‘Fashion’, the premise of which provides an amusingly literal framework for today’s interview. As he explains in the intro to the song in his leisurely drawl, “You know, I love to dress… Clothes is there – you might as well take advantage of it. It’s just fun, bro.” To ram the latter point home, props in the accompanying video include a real life zebra and a white Rolls Royce. Meanwhile, Jimothy lolls on a leather sofa in a cobalt fur jacket and crystal-covered Gucci shades, steals a bottle of champagne from a Sainsbury Local, and does his trademark hip wiggle in a succession of primary-coloured slacks.

It’s this vague whiff of the ludicrous that has made Jimothy a divisive figure. His deadpan delivery is less fire in the booth than easy-going Sprechgesang, the well-to-do North London accent and clear diction jarring with the use of street slang. Lyrics are literal and rhymes often ridiculous (“I’m gonna have to dip, I’ll see you soon / Baby, don’t get sad, when I’m rich I’ll take you to the moon”). So far, all the subjects covered have been simplistic, including his love of London transport (‘Subway System’), bilingualism (‘I Can Speak Spanish’) and plans for romance (‘Future Bae’).

Mirroring the minimal production of his iPad-pop, his homemade videos have an endearing DIY quality, and through them he’s established his own visual language. For example, by now we know to expect sporadic subtitles, rotating £20 note graphics, and Jimothy in smart-casual dress, showcasing his extremely gif-able dance moves in an array of urban locations, including on top of high rise buildings and bus stops. In a genre that prides gritty authenticity, Jimothy’s benign playfulness stands out, earmarking him as either endearingly naive or wilfully provocative. After our afternoon together, I decide he’s probably both.

Certainly, he seems to benefit from an enviable lack of self-consciousness. In the opulent Gucci store on Old Bond Street he breezily dismisses their trainers as “horrible”, within easy earshot of staff. In the walnut-panelled rooms of Ralph Lauren, Jimothy tells me that, unlike most people, he much prefers the Polo Bear motif to the iconic Polo player logo. “It’s cute,” he explains. “Shows you’re not insecure. Shows you don’t take life too seriously.”

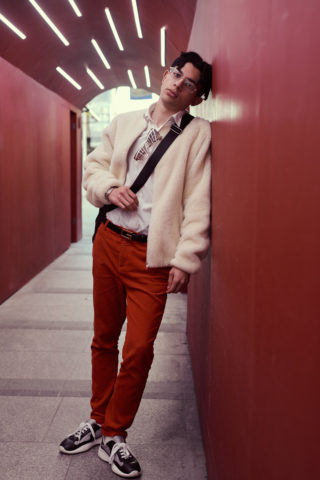

Though still probably only in his late teens (his exact age is being withheld to preserve mystery), Jimothy is a seasoned aesthete, with a precisely defined personal style. He aspires to the preppy look preferred by “posh, old people”, boarding school kids and city workers, citing his staple pieces as cable knit sweaters, gilets, cords, pinstriped silk shirts and heritage labels. He’s not precious about seeming androgynous: the Gucci glasses from the ‘Fashion’ video were from the ladies department, and he intends to start wearing handbags as necklaces. He loves primary colours, happily philosophises on his favourite shade combinations (red with blue, and green with black) and proudly offers an itemised rundown of today’s outfit. It is as follows: navy and white Prada sneakers (£460), scarlet Ralph Lauren cords (£50 from eBay), white Oxford shirt from Uniqlo (£24.90), Gucci belt (£265), Prada shades and Coach messenger bag (gifted), cream fur jacket (on loan from his older sister), Slazenger socks (£2), and briefs from a Spanish supermarket (around €1 for 3 pairs).

Jimothy will happily concede to being materialistic, but he retains a sense of perspective about his expensive purchases: “I love brands. But if [something I buy] breaks the next day, I’ve got no right to be upset about it. No right. Because as soon as I buy something, it’s already money down the drain.” If he seems surprisingly sanguine at the idea of squandering cash, it’s a position he’s only had the luxury of indulging in recent months.

“The first time I actually went shopping by myself and bought something was literally six months ago,” he recalls later, reclined on a sofa in a quiet nook of Soho House. “That was Lacoste. Basically, I got money from merch, and that was the very first time I had any money ever in life, despite what people think. Lots of people think I’m a rich kid and I’m really not. My mum would only give me £10 maybe every three weeks and every time she did that she was so upset that I would just spend it on spray cans.

“It’s weird because I’ve never had money, but I’ve always dressed really smart. And that’s because my older sister worked in retail and she was really into fashion. She would be onto me, like, ‘Do you want me to get anything for you?’

“But I don’t shop in these shops regularly. I had guilt when I first went to the Gucci store the other day. I felt really weird. I felt a bit depressed, even. But I need to remind myself that I left this much money in my savings account, and I’ve left this much money to spend on food and clothes. And that I’m here because I am becoming a little successful in life.” He describes designer clothing as “a medal” in that “it reminds me that I’m doing well, and it motivates me more and more each day to carry on and chase my dreams.”

Aside from the influence of his sister, it was graffiti culture that first sparked Jimothy’s interest in fashion, when he was hanging out around Gospel Oak from the age of 11. “I was always just in a typical tracksuit with quick [Nike] Air Forces. I had no style,” he laughs. “Because that’s just how everyone dressed, and you’ve got to look the same and what not.

“There were these older graffiti writers in London that I looked up to. I thought they’d be dressed exactly like me but then I met some of them and they were all extremely classic and smart. They just dressed like they had money: slim trousers, tucked-in shirt. I looked at that and then I looked at my situation and I thought it would be so cool to do the same, first of all because I love this style, but second because dressing like a rich guy even though you’ve got no money is fun. Even though your mum’s been on the dole for over 25 years and your dad’s never worked a single day of his life. Because no-one in my family has money. But when I was dressed like a rich guy, I just felt amazing. I felt amazing. So ever since then I was just dressed really smart.

“And then later I watched this documentary on kids in New York in the ’70s. And they all dressed how I dress now: colourful trousers, [Adidas] Sambas or any slim trainers, tucked in shirt, sweater, a nice old-man-looking jacket, flat caps. I was like, ‘This is where he got it from. This whole time I’ve been dressing like these kids without knowing.’ And after that I really, really stuck with my style.”

We exit Burberry and head towards Prada on Old Bond Street, past a gaggle of wealthy teenagers and two immaculately coiffured ladies being helped into a car by their chauffeur. It’s an uncharacteristically mild October day, and businessmen are visibly flushed in their bespoke suits as they plough past us. A chrome Lamborghini cruises past, driven by a man in his 50s. While my default response is to roll my eyes, Jimothy is delighted. “He looked so happy,” he smiles, as it vanishes around the corner, “I love it!”

Jimothy’s parents split when he was barely one, and he, his sister and brother were raised by their mother. They lived in Primrose Hill, a notoriously well-heeled enclave of Camden, at the top of Regent’s Park. “The council gave us the flat in Primrose Hill thirty years ago, so it’s all a blessing,” he says, gauging my surprise. “See, this is the funny thing: the way I talk, the way I walk, the way I dress, where I live – people are convinced I’m rich. But I talk like this because I’ve been around lots of posh kids, and because it’s a better way of talking.

“And of course, my mum’s from Spain so she has class. So she’ll be poor but she’ll also be dressed like a rich woman, and the house will look well designed even though it’s a council house. A lot of people have money but they have no class. A lot of people have money but they don’t know how to dress. Do you know what I mean? Money doesn’t mean anything.”

He mixed with affluent kids at the local park from a young age, only to be separated when they went to private school. When they hit their teens, Jimothy invited himself along to their house parties, and his socialising then snowballed to the point where he was hanging out almost exclusively with rich people. “Literally, I don’t have a single friend in my situation, living in a council house,” he says, shaking his head. “It makes me sad sometimes. But if it wasn’t for those friends I wouldn’t be the person I am now.”

I wonder if Jimothy ever felt intimidated by his friends’ wealth. “Definitely,” he nods. “At first I was very insecure about it. But that was when I was 13 and dressed in a certain way, and all the other kids would be dressed really smart. They would make me feel really bad. The funny thing is, now I’m the one dressed really smart, and they’re dressed like they’re from a council house. They go to private school, and they’re trying to dress like a roadman, trying to dress like a hood kid.”

While there was once an element of Jimothy dressing to deliberately confound people’s preconceptions, he now feels conflicted about being mistaken for a rich kid. “The reason why it hurts my feelings so much – and no offence, because I love rich kids – is they all know how to play the piano. Their parents could afford to lend them a decent amount of money or a car for their music videos. They could start a career easier than someone with not much money. Me, I literally started with nothing. It was all me, me, me, me, me. So when people think [I’m a rich kid] it implies I didn’t work for anything; that it was given to me. And that really, really disrespects me, my family, everything.”

If Jimothy was initially a fish out of water in his friendship group, he felt even more out of place at the special school he attended from the age of 13, due to his dyslexia and dyscalculia. The way he tells it, he knew he didn’t belong there but stayed because the work was easy. Had he left, he might never have pursued music.

“At the special school there are no kids with insecurities,” he explains. “So I wasn’t shy to write a song and put it out there. I wasn’t shy to make a music video. That school made me do music, basically. And the work was easy but that was freeing. That school gave me a free-thinking mentality and a higher consciousness.”

In some respects, he believes the school protected him. “It did get to a point where it was then scary to go to a mainstream school. Because I thought to myself, actually, if I go to a mainstream school and someone laughs at me for dyslexia, or for my parents having always been living off benefits, or for not having a father figure, I don’t know how I would react to that. [I don’t know] whether I would fight them, whether I would then not go to school and end up on the streets selling drugs. If I went to a mainstream school – and it sounds really harsh and kind of depressing, but it’s true – but if I went to a mainstream school I’d either be dead or I’d be prison. And that’s why I always say with my songs that Jimothy is blessed.”

The floors of the Gucci store are covered in geometric patterns, in tiles of purple, red, grey and white. There are mirrored walls and staircases lined with plush velvet in a vivid shade of oxblood. In the womenswear section, we’re admiring the craftsmanship of a collection of luxe satin bombers in jewel colours, each intricately embroidered and painstakingly stitched with sequins. Jimothy’s eyes are drawn away from the glitz to a monochrome coat in the iconic interlinking GG pattern. “I’d buy that for my future bae,” he nods.

There wasn’t money for piano lessons growing up, but Jimothy believes he inherited a “gene of rhythm” from his dad, and a fascination with melody from his mum, who was always playing R&B at home. Grime was a formative influence, as was UK garage, which he was exposed to via the older graffiti writers. “I’d listen to anything,” he remembers. “If it sounded good in my ears, I’d put it on, whether that was Somali pop or classic house.”

Playboi Carti, Lil Uzi Vert, Octavian and Sheck Wes are all mentioned when I ask Jimothy about who he sees as his peers. “Basically, it’s music that you can dance to but music you can sit down in your room to by yourself,” he explains. “Tomorrow, I could come out with a house tune, I could come out with a rock tune, I could come out with a bedroom pop tune. Nothing is ever intended. You’ve got to come to [my music] with no expectations.

“A lot of people think I don’t take music seriously,” he continues, “and that’s super disrespectful. I will not put out anything I don’t like. So many producers send me so many instrumentals, and I am super particular. It offends me when people come up to me like, ‘Oh mate, I love your stuff – it’s funny.’ I wanna hear, ‘I love your stuff, I love your instrumentals, I love your lyrics.’”

And yet, I counter, surely he must concede that there’s a vein of humour running through his work? “Oh yeah, definitely,” he smiles. “And I love to shock people. I’ve always been a bit of an attention-seeker. But I think it depends. If people only find it funny and they don’t appreciate anything else about it, it offends me. Like, I find my own stuff funny, but when I’m doing the instrumental, I have so much passion and love.”

Considering the rigour he applies to every other area of his life, I don’t doubt Jimothy’s discipline in the studio. Today he’s fasting, which he does two consecutive days a week, the rationale for which is apparently to “repair DNA”. “When your digestion isn’t going your body then focuses on cell replenishment,” he elaborates. Then there’s the cold showers he takes every morning, and the nights spent sleeping on a hard floor.

I wonder at the rationale behind his asceticism. What tangible benefits does he actually take away from such restrictive rituals? “The main benefit I see from it is mental strength. So when someone says to me, ‘Can you do this?’ it’s easy for me to do it because my brain is so strong. You know, I’ve had no father figure whatsoever. I’ve never had someone to say, ‘Good job. Focus on your goals.’ I had to find that in myself.”

En route to Soho House for our sit-down chat, there’s a pretty uncanny coincidence. We’re discussing fame and the loss of anonymity. “I’d love paparazzi following me,” Jimothy insists. “I’d love it.” Suddenly, a young man steps into Jimothy’s path. “Can I just interrupt, man?” he asks, clearly attempting to play it cool. “I think your shit’s dope.” They take a selfie together, the fan departs and we continue our journey, Jimothy wearing a contented grin.

As our conversation draws to a close, the subject turns to aspiration. For Jimothy, is success ultimately measured in luxury clothing, or is there something loftier he’s aiming for? “A good income,” he replies without any hesitation, “to the point where I’ve got my own house and I can treat myself, and I can have kids and I can have a wife.” So in essence, he’s seeking security? “Definitely. It’s something I’ve never had. It would just be amazing to have it. Something that seems a little bit impossible.”

What else? “Having a fan base that loves me and I love them. I love being a role model. I want all my fans to be happy to express themselves and to have fun at my shows and to just go crazy. To let their emotions out and to let go of stress, and to not be insecure and not be those kids that judge other people. I want my fans to just be nice people. Like me. Don’t judge people, don’t call other people names, treat everyone with equality. Simple things really.”

While it’s heartening to hear the connection Jimothy feels to his fans, I wonder if his increasingly lavish lifestyle might eventually create resentment. “It should be the opposite,” he insists. “They should look at me and think. ‘1. I’m happy for Jimothy – he’s doing well. And 2. that’s motivation for me.’

“When I now see someone with a sports car it makes me happy, like, that could be me one day. That motivates me. I’m not gonna hate on them; that’s how unsuccessful people think. You’ve got to be happy for that person and aspire to those levels.” The way Jimothy reacted to the owner of the Lamborghini earlier, I ask? “Yeah exactly. Stuff like that makes me happy. You’ve got to use it as motivation. You can be like that one day if you just follow your dreams and you’re smart.”