Nico: the Manchester years – life after The Velvet Underground

"She said it reminded her of Berlin, the ruined city of her youth.”

"She said it reminded her of Berlin, the ruined city of her youth.”

Nico modelled for Chanel, appeared in Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, sang for The Velvet Underground and released a string of truly inimitable solo albums that influenced a vast range of artists from Elliott Smith to Throbbing Gristle. Yet despite such accolades landing her with true cult hero status, there’s some periods of Nico’s life that don’t fit as neatly and glamorously into her timeline: such as her seven years spent in Manchester between 1981-88.

Moving from Paris to New York, the German-born artist left the modelling and acting world and leapt into a musical one, famously falling into Andy Warhol’s circle and onto the The Velvet Underground’s seminal debut album. Between 1967 and 1974 she then released four solo albums. Her debut, ‘Chelsea Girl’ – penned by friends and collaborators like Lou Reed, John Cale, Bob Dylan and Jackson Browne – is a collection of wistful folk-pop, humming with breezy, infectious melodies and hushed vocals that feel like extensions of the softer side she brought to the Velvet Underground.

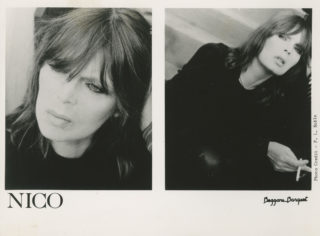

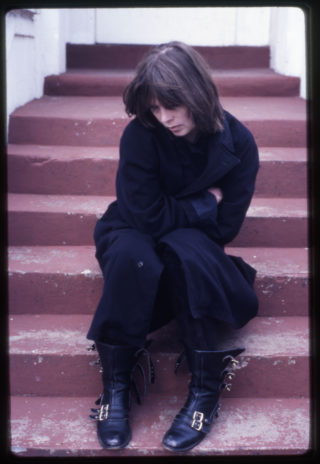

When encouraged to write her own material, Nico gained a new sense of individualism on albums such as ‘The Marble Index’ and ‘Desertshore’. Gone were the gently plucked acoustic guitars and sweet vocals and in was a droning harmonium, songs about death and decay and a voice that plunged new depths and forged new tones. This period birthed a newfound identity both sonically and aesthetically: gone too was the blonde hair and pristine white clothing and in was dyed hair, black clothing and scuffed motorcycle boots.

Nico became seemingly less concerned about appearing conventionally pretty, vocally. After over a decade of feeling defined by her appearance and beauty, she embraced a vocal style that seemed to both challenge and redefine what constituted a beautiful voice, as it often echoed out like a ship’s foghorn slowly rumbling amidst a thick smog. Not only did this strange yet innovative new music – along with her newfound anti-conventional aesthetic – come to define Nico’s most creative period, but the albums became the definitive avant-garde neoclassical works of the entire era. As John Cale – who produced the bulk of Nico’s solo work – says in the 1995 documentary Nico: Icon, “If you look at what she was writing at that time, there was nobody else doing anything else even remotely similar.”

What comes next is a lesser known, unexplored black hole of Nico’s life.

After 1981’s ‘Drama of Exile’, Nico found herself in the rather unexpected city of Manchester and remained there for the best part of a decade. Initially paired up with a local promoter (who replied: “who’s he?” when asked to put her on), Nico soon found herself managed by this man, Alan Wise.

James Young, who became a piano player in Nico’s band between 1981-86 and wrote a memoir about his time with her (Songs They Never Play on the Radio), recalls his first unexpected encounter with her, saying: “Out of nowhere there was this German lady on my doorstep with an old friend, Alan Wise. Before I knew it, Nico was taking over my flat. First she colonised the bathroom and once she’d ‘freshened up’ she took over the kitchen, as she wanted to make lentil soup. She carried a bag of dried lentils with her, like a nomad.”

Wise had looked up Young when on tour with Nico in Oxford. You might have guessed that the freshening up Young refers to was actually them seeking out a place for Nico to take heroin. By this stage she was deep into addiction with the drug. Later on that evening, Young got to see the other side of Nico, the one that wasn’t shooting up in his bathroom and making soup in his kitchen. “I was struck by the individuality of her music and persona, singing those strange medieval lullabies at her harmonium in an Oxford disco. It was totally incongruous and rather wonderful. I immediately grasped that this was a unique and original artist.”

Young soon found himself leaving his academic life in Oxford behind and moving to Manchester to join her band. Basing herself in Manchester during the 1980s may seem a bizarre choice for someone who has a history attached to the elegance of 1950s Paris or the bohemian boom of 1960s and ’70s New York but Young feels the city was something she could relate to. “Nico liked Manchester. It was a dark gothic city and was in a state of semi-dereliction at the time; empty Victorian warehouses, factories closing down. She said it reminded her of Berlin, the ruined city of her youth.” Graham Dowdall, who was also in Nico’s band, echoes that she gravitated towards the “post-industrial landscape and griminess,” but also adds that there was the allure of “cheap smack.”

Nico lived in various places in the city, from flats in Prestwich to squats in Hulme. Young recalls her having close to no possessions during this period. “Just her harmonium and a bag with stuff in: her notebook, drug works, incense and reading material.”

Stella Grundy saw Nico for the first time at 16 and had her life changed. At Manchester Library Theatre in a room thick with cigarette and marijuana smoke, she recalls a set that was “beautiful, powerful and dark.” Ignoring the heckles for Velvet Underground tracks such as ‘Heroin’, Nico played Grundy’s request of ‘Frozen Warnings’, which she’d nervously called out for. “I was enraptured. From that night on I decided I wanted to be an artist, writer, singer – anything to be part of this world.” Grundy would go on to be in bands such as Intastella and in 2007 wrote a multi-media play about Nico that ran for two years and is also now available as an eBook.

Grundy recalls seeing Nico drink in the local pubs of Prestwich, where apparently she would play pool with the locals who had no clue who she was. Occasionally she’d be pestered by people that did. “She didn’t like fans of the Velvet Underground mithering her about those times, although she was happy to write messages and autographs for people when asked. I’ve been shown a few of these items. Some people were unkind to her and took advantage though.” Grundy saw this up close as her boyfriend at the time even went backstage and stole her heroin needles as some sort of cultural memento from the “queen of the junkies”. Grundy even recalls being told that someone had stolen her diary.

The day-to-day existence of Nico during her Manchester years resembled that of most heroin addicts: shooting up or trying to get gear to shoot up. She described herself as reclusive and lived in places with blood-splattered walls from syringe splats, which she shared with other local users and musicians including John Cooper Clarke. There were periods she would live off a diet purely of custard and would claim, with some pride, to go prolonged periods without bathing. Young feels that this period of perceived disintegration was not necessarily all sordid demise and the destruction of a talent but instead an extension of Nico’s redefined personality. She took pride in her greying hair, sagging skin and needle-marked arms because they were the antithesis to everything she had once been told she was wonderful for. “She seemed to be embracing the scars of time and addiction saying ‘this is who I am.”

As a result, in terms of writing and recording new music, the Manchester years were some of Nico’s least productive. But fast money was often required to pay for her heavy addiction, and a way to get that was by touring. Wise would organise shows in the UK, across Europe and even as far as Tokyo and America – something that could often prove problematic given the needs of Nico, as well as the needs of some of the other touring parties who had their own chemical needs and personality idiosyncrasies. Young remembers “a hopeless tour of the USA, playing clubs in the boiling heat of summer. No money. Nico withdrawing. Arguments and bickering, all in a car with the air conditioning switched off to save fuel.”

Both Young and Dowdall remember the repeating drawled line of “are we near the border yet?” coming from Nico when on tour and then a sort of pandemonium erupting: things being hidden and stashed, including in Nico’s underwear and in her anus. Young recalls even being given a handful of used syringes from her that he quickly had to throw out of the window into the nearby water before reaching border guards. “Her running out of smack at the wrong time – like before a gig – was always a big problem,” he recalls, “meaning one of us would have to go out and hustle for a connection on the street and inevitably get ripped off.”

On top of this, Nico and her manager had a volatile relationship on and off the road. Dowdall describes it as: “very complex and not entirely healthy, although both got a lot of positive things out of it.” Similarly, Young repeats this dysfunctional image. “Alan was a very intelligent guy,” he says. “He was also highly emotional. He developed a passion for Nico that was not reciprocated and this was a source of deep frustration for him. They had endless arguments. They lived by constantly tearing at each other like a crazed married couple. At the same time they were close friends. I would say that apart from Ari [Nico’s son] Alan was closest to Nico. I was never that close to her; my relationship was more professional. I realised early on that getting close to Nico meant sharing a propensity for addiction. Alan was a valium addict and his father had a chain of pharmacies. He understood the chemistry of need, he could facilitate. He responded to people who were ill, whether physically or psychologically. He went under the sobriquet of ‘Doctor’ and took damaged people into his care.”

Stella Grundy feels this dependency was a potentially damaging one at times. “As a child of the 1930s she did defer to men a lot,” she says, “allowing them to make decisions for her and not always the right ones. She would constantly be without enough money and of course heroin does not come for free. I actually think she just allowed people to control her like the drug. She was brave and talented and I believe lacked confidence and still felt she needed a man to help her when actually she didn’t. Her best work for me was her solo, playing the harmonium.”

Despite the savage addiction that controlled much of Nico’s existence, and the occasional shambolic and failing gigs in which her dark European music felt out of place with the shiny pop of the era, there were also moments of magic to be found. “She was actually really positive and encouraging to work with,” recalls Dowdall. “I remember playing with her and the mic was broken but Nico started to sing acoustically. Every hair on my body stood up. Her voice was huge and resonant with all the weight she carried. She also taught me instantly to deviate anything, she was a trooper – no mic, no problem.”

Nico and her band, the Faction, would make one last studio album, 1985’s ‘Camera Obscura’. The following year she made some significant changes in her life, as Young tells me: “In ’86 Alan persuaded Nico to go on the methadone programme, especially since her main reliable dealer had been busted and was in prison. I think this was a mistake. Methadone is a horrible drug, it zombifises people. I didn’t like what it was doing to her. I guess it made her easier to manage – no more running around to find a connection. Her health seemed to decline after that. We did a concert in Berlin at the Planetarium together and it was clear that she wasn’t well. She wanted to go to Ibiza to rest and review her life. I think she knew she was dying.” A short time later, in 1988, whilst in Ibiza, Nico did die, suffering a brain haemorrhage whilst out on a bicycle.