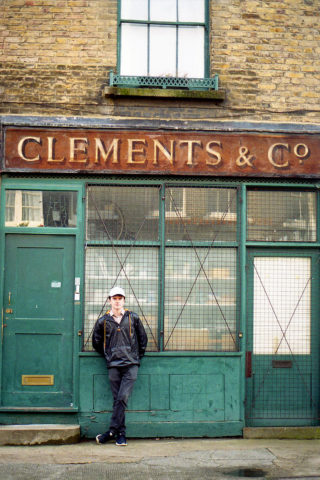

Oliver Coates recently adopted a kitten. He’s named it Alanis – after Morissette, of course – but not out of admiration for her musical exploits. Instead, he explains, it’s in homage to the Canadian singer’s recent and unexpected rejuvenation as an agony aunt in the Saturday Guardian. “That’s actually quite ironic,” I suggest, mischievously, to the concert cellist-turned-electronic producer as he’s being photographed. He takes the bait, and starts to point out how Morissette’s most famous song is genuinely full of ironies, and not merely ironic because, as the stand-up routine goes, it describes no ironies whatsoever.

Coates excitedly tells me of staying up late discussing the idea of irony with his friends as a result of all this, even going so far as to look up the word in the dictionary to gain objectivity (definitely, I’m informed, not an ironic act). The upshot is that Coates is certain that Alanis (the singer, not the kitten) is on firmer ground than many would believe.

He tells the story with a smile, as if to acknowledge its inherent ridiculousness, but there’s an accompanying seriousness to his voice that reveals a sweetly earnest predilection for leaving nothing in his life unexamined. It’s a habit that, over the course of the next hour or so, will play out in a series of intense, tangential and largely unprompted speeches about the contemporary classical composers Feldman and Xenakis, electronic producers Actress and Shackleton and the works of Hitchcock, Kafka, Christopher Hitchens, Eco and Beckett. Even the socio-cultural mores of music in Russia receives a brief heartfelt tribute.

In short, Coates is a serious man. His meticulousness and super-analytical approach to life has, inevitably, fuelled his music-making, too, and nowhere is it more evident than in the unusual creative process behind his second album, ‘Upstepping’: nearly every sound on the record, which owes a debt both to the garage rhythms of ’90s London pirate radio and to 20th-century classical music, originates from Coates’s cello, which he has played and then manipulated to mimic hi-hats and kick drum sounds, washes of synths and dense white noise. From one angle, the album is a demonstration of his microscopically detailed mastery of the instrument (Coates received the highest mark ever given to a graduating student from the Royal Academy of Music, and his work as a soloist is how he pays the rent), but from another it’s a rather touching act of devotion to the music for which he has an almost cosmically reverential love.

Coates began playing the cello after seeing one in a neighbour’s house in Wandsworth when he was six, and by nine he knew he was going to be a musician. “There was no question,” he says, of his early determination. “My mum said, ‘oh that would be a nice life, but I imagine it would be a hard one,’ so I knew that if that was my decision, it had to be intense; I couldn’t do it half-heartedly. And I think I’ve been doing that – taking that decision just not to mess around – ever since.”

He spent his teens listening to everything from Radiohead and the Manics to Shostakovich and Prokofiev, while becoming increasingly proficient at the cello (“When they put a book in front of me and said ‘I’d like you to learn this by next week’, I found that quite easy,” he admits), but his first exposure to the dance music that has found its way onto ‘Upstepping’ was via Coates’s teenage obsession with a specific style of drum programming. “There was a time in the mid-90s where you got a particular kind of snare rush on pirate radio, and I spent my Sunday afternoons searching for them on the car radio,” he explains, painting a vivid picture of an awkward, musically prodigious teenager academically deconstructing the somewhat feral worlds of illegal urban broadcasting from the passenger seat of a parked family hatchback. “I was just obsessed – I didn’t know how they did it. I was so impressed with the amazing snare programming of the time.”

He soon developed a taste for the Warp Records stable and started messing around with drum programming software himself, creating, he says, “beats that were a bit Squarepusher-esque”, but found it difficult to get beyond what he describes as “just noodling”. The problem, he insists, lay in setting limitations: “When I was just performing, I liked that the texted, scored, prescribed stuff was all there, on the page. I got really into memorising and learning scores,” he explains. “It was nice when somebody else arbitrated the limits.”

However, now 33, and with over a decade of international performance behind him, Coates has discovered a little more confidence there. “Now, I’m the one deciding the numbers,” he says. “I am more comfortable these days being the person who sets the limits. It’s like everything I’ve done in the last ten years, every situation where there’s been an externally imposed limit, where I’ve done that phrase four times but I wanted to do it twenty times in ten different ways – I couldn’t, because I wasn’t the author. I’m much happier now with this quiet agony of counting out and designing structures of my own.”

For all the confidence, though, Coates’s potentially neurotic predisposition for listening on a granular level is the basis for what makes the dancier half of ‘Upstepping’ so captivating: his study and almost preternatural understanding of how electronic music works allowed him to replace each element of classic garage and techno drum sequences, hit by hit, with his own sounds, finishing up with something that sounds at once familiar but also sonically curious.

“I was all too aware that an 808 clap has a rich history and by using it, you’re instantly positioning the listener,” he admits of his painstaking sequencing process, making a persistent sort of karate-chop motion into his open palm as he says each phrase. “So I started looking instead at the function of a kick, the function of a high-hat, the role it plays in the track, how it helps the music, why it works.

“I’d look at each sound’s potency in the overall track,” he continues, “and then ask if the sound palette could be widened beyond the history of sampling, beyond the history of drum machines, and how that could involve, and evolve, this instrument that I’m meant to be so proficient on. I wanted to unlearn the instrument and then find new physical ways of playing it.”

If the results of Coates’s tinkering appear joyfully uncanny to anyone tired of the more sterile, hermetically sealed end of dance music, the other four tracks on ‘Upstepping’ are less straightforward. Dark and beatless – or, at least, with no pulse you could dance to – they hark back to Coates’s interaction with the music he actually performs rather than that which is the product of laborious dissection and reassembly.

While all composed by Coates himself, taken as a set they bear striking resemblances to specific pieces of 20th-century classical music, (‘Memorial For Hitchens’’ direct quotation of the opening of John Tavener’s ‘The Protecting Veil’ being the most immediate), suggesting that perhaps, for all Coates’s recent dalliances with composition, his habits as a performer die hard: even in his most creative mode, he can’t help but reference the pieces he knows and loves.

He half agrees. “For so long, all my work has been in interpretation,” he says of his main gig as a performer, and his conversion to composer. “Something is put in front of you, and you are tasked with going out on stage and owning it. Right then, you’re the conduit: at that moment, the composer is dead, because you’re the only person who can convince the audience that what everyone in the room is doing is worthwhile.”

I ask him whether he feels that the performer’s importance is therefore overlooked, and perhaps not as celebrated as the man or woman putting the dots on the page. He begins another intense screed, this time about Christopher Hitchens, eventually proffering the theory that Homer didn’t really exist, and that his writings are just amalgams of “many fractured stories”. He starts to debate with himself notions of authorship in the abstract.

Does he see any correspondence there to his own work? He frowns. “Well, I don’t think I am the author of my album,” he says, finally. “I think there are many tunes running through all of us at any point, and maybe I’m just a conduit.”

Perhaps that’s Coates’s oblique way of acknowledging the array of influences that he’s whittled into ‘Upstepping’. More likely, he’s just enjoying the continued musicological stone-turning and hoop-jumping. Either way, however, the contents of his record render it all somewhat academic: for all the highfalutin philosophy he bounces around, Coates has also made something of a banger, ripe for remixes and playing on big sound systems. One can pick it apart as much as one likes, I suggest, but it’s worth remembering that his music is also fun.

“That’s relatively new to me, actually,” he agrees, when suggested, in the nicest possible way, that he might lighten up a little. “For a long time, I had this idea that playing the cello in this scripted, disciplined way was what I was best at. And I agree with discipline and I agree with being able to play your instrument perfectly because it gives you confidence to walk into any situation, but in terms of developing aesthetics it leaves a long way to go. Now, when I play or write, I think about where people want to hear my music, and where people want to move to it.”

Turns out, though, that the answers to those particular questions are another set that are pending: “I had an answer for the last record,” he says, when asked in what context he would like people to listen to ‘Upstepping’. “I talked about being in a remote Scottish island with a glass of whiskey. But for this one I don’t know really.”

He pauses and stares up at the ceiling, and a eureka expression crosses his face. “Actually, I like it when I’ve heard it coming out of someone’s laptop speakers. I heard it on the laptop speakers of a friend of mine in an airport and I liked the compressed, tinny aspects of it. I’m not worried about masses of bass. It felt very open, you know?”

Perhaps that encapsulates the oddness of ‘Upstepping’ – it’s an album inspired by underground electronics and claustrophobic new music, yet best listened to off a laptop in somewhere as expansive as an airport terminal. It’s an unusual choice, certainly, and maybe even, given his industrious attention to audio detail, an ironic one.

“Don’t you think?” I ask him. He grins, and says that reminds him: he must get home to the cat.