Shouting at Walls: Shame learnt everything about the music industry from a crumbling pub in south London

That's entertainment

That's entertainment

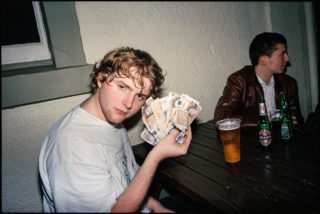

Over a table strewn with cans of Aldi own-brand lager in a Liverpool beer garden, Shame are recalling on-tour war stories. “Do you remember when I got on stage and was sick all over Charlie Boyer & the Voyeurs’ keyboard as they played?” says the group’s lead singer, Charlie Steen. “I was just hallucinating, seeing eyes everywhere,” he recalls. There’re more tales – of being banned from a Dublin Wetherspoon’s because the staff mistook their tired, on-tour state as a sign that they were drug addicts, or “skags” as they were called before being asked to leave; of the 30p pints in a 24-hour bar in the Czech Republic that ended up in them encountering a homophobic club owner who extinguished lit cigarettes on his own hand because he was so angry with the band and their perceived gayness as they gyrated around the venue to the music of their friends band, HMLTD. There’s more hallucinating that involved almost eating a raw chicken believing it to be a freshly roasted one; Evangelical Christians trying to save and convert guitarist Eddie Green as he crashed into their tent in the black of night in the woods on an island while blind drunk and trying to make it back to the hotel; and there’s a heroic, convoluted, incredibly lengthy (and successful) plot of the band travelling to and breaking into Glastonbury Festival to play a gig there in 2016. All of Shame are barely out of their teens and have only existed as a group for a few years but they’ve made good, fun and mischievous use of their time so far.

Such tales paint a picture of a drug-addled, crazy and chaotic bunch who you’d cross the road to avoid making eye contact with – an image no doubt reinforced by their music: a snarling and seething blend of urgent post-punk, brooding atmospheres, guttural vocals and precision sharp melodies that feel born from 1970s Manchester but are funnelled through a contemporary sheen and political bite that feels unequivocally of the moment. However, in reality, Shame are an affable bunch and are nothing more than a group of very young men having a mountain of laughs in an industry they are already wise enough to know can be as fickle as it can treacherous.

“I think a lot of people are sometimes pleasantly surprised by us,” says bassist Josh Finerty, “because they hear things like ‘furious young punk band from London, crazy young kids who are going to fight each other and piss on you’ and then you come see it and whilst Charlie is a visceral frontman the rest of us are just fresh-faced cherubic little kids really. It’s energetic but I always try and have fun with the audience, that’s always the main part.” This is something that Eddie Green echoes: “Yeah, it’s not like we’re going to come and make it really intense and nasty,” he says. “Some bands want to make you feel uncomfortable and we’re not one of them.”

Perhaps Shame’s reputation as an unapproachable band of snotty, outspoken, angry kids comes from the origins of where the band was born and cultivated: The Queen’s Head, Brixton. The pub-come-doss house was the place that The Fat White Family essentially lived and operated from and it was the pub that made national news when the band [Fat Whites] stood atop of its roof with a giant banner proclaiming ‘The Witch is Dead’ in relation to the death of Margaret Thatcher. Now a gastro pub, for a period the place had a reputation for its behind-the-scenes anything goes vibe, solidifying it as some sort of sordid den of inequity, a reputation that the Fat Whites themselves only strengthened. The band saw all of this up close because it became their second home and rehearsal space because drummer Charlie Forbes’ dad was friends with the pub’s landlord, Simon Tickner. In fact, Forbes had been thrust into this unusual world from an early age. “I had Christmas dinner in the Queen’s Head a few years before and I fell down the stairs carrying one of the Fat Whites’ dinner. I was only about 14.” It also transpires that what you may have heard or thought about the goings on in the place were almost certainly accurate. “Everything you’ve read or any preconceptions you have about that pub, are 100% true,” Green says, with guitarist Sean Coyle-Smith adding: “If not, it was under exaggerated, some dark things happened there.”

Still, it gave them an affordable space to rehearse, in a supportive and judgment-free environment filled with people from a vast range of ages and backgrounds that went far beyond that of their school classmates. This is something Shame feel has been crucial to their development, not just as a band, but people, too.

“It was an eclectic environment,” Steen says, “Anyone could walk into that pub but at the same time it was like a massive community and if you accepted it, it became like a second home. You could walk in there, walk behind the bar, pour yourself a pint and go upstairs before the landlord had even woken up.”

The band – five school friends who started making music together out of simple boredom – were there every single day for a year. “It was a very slow progression into doing anything resembling a proper practice because the drums were pretty much made out of gaffer tape,” says Steen as he cracks open another St Etienne. “I didn’t have a microphone for two months, I just used to cup my hands and shout against a wall. Also, none of the equipment was ours, so it was like, will there be a bass amp in there?”

“We got pretty creative because of it,” says Green.

The space opened Shame’s eyes and minds to a lot of things they hadn’t been exposed to before. As Green puts it: “When people our age were just doing normal shit, we were getting fucked up with 45-year-olds.”

They would be banned for overstepping the line one night but welcomed back the next; they would scrub the floors of the pub despite them feeling like they would never get clean; they would befriend people from bands such as Stiff Little Fingers and Alabama 3 and listen keenly to their tales of being churned through the soggy guts of the music industry. “They gave us advice that is still really fundamental to what we do today,” Steen says. It also gave them a stage and a place to harness themselves as a ferocious live band. The first show they ever played was under the insistence of the landlord, Tickner. They pulled in four whole mates and played before that evening’s reggae night started. From that night the group still have one song in their set that they play today called ‘One Rizla’, a self-deprecating number that leans closer to the more straight-up, Cribs-like, indie side of the group that they occasionally veer into, rather than the Fall-like ‘The Lick’ or the frenzied jagged burst of ‘Concrete’. “We wrote that song [‘One Rizla’] at 16 when we were at the Queen’s so lyrically it’s not much – it’s quite immature – but it shows where we were at that time and when we started the band…” Steen is interrupted by a middle aged man in a Crass T-shirt who asks for his ticket for tonight’s show to be autographed by the band. He then continues: “I wasn’t a musician, we were trying to find ourselves and lyrically I thought songs had to be about being in love or being heartbroken but at that age I was just a chubby stoner who didn’t ever get any girls, so I could only write about something that related to me. All the music our friends were listening to, mainly rap, was much more narcissistic and bragging and I couldn’t really relate to it.”

Shame’s reputation as a live band caught on as they grew and developed, attracting the usual industry buzz that the group laugh about when they tell me they ended up putting someone from Ministry of Sound on their guest list for a show at DIY venue and bar, The Windmill, in Brixton (as part of a regular series of shows they put on with other bands under the title Chimney Shitters). But they were keen to avoid falling into traps that they had heard fellow comrades back at the Queen’s stumble into. “Thankfully we were brought up in this pub that had a lot of people that had worked in the music industry. They’d all made some of the worst decisions that you could make in the industry, so we learnt a pretty basic knowledge of the do’s and don’ts,” says Coyle-Smith. Steen likewise knew that allowing the group to find themselves was the key element at this early stage when seeds were still being sown. “We found ourselves lucky enough to know all those people and hear all those stories, so we didn’t jump at the first bit of interest, we knew about the smoke and mirrors and just wanted to write more songs and play and see what happened.” Forbes and Green were adamant if and when the time came they would be avoiding major labels.

Green remembers: “We had this one guy come down from a major and was giving us the whole routine, like, ‘guys, I literally have goosebumps right now,’ and my dad was there and just said, ‘you ought to put a cardigan on, mate.’ That was rule number one to me – don’t sign for a fucking major. I don’t want to tar every major label with the same brush but I’ve always had that mentality.”

The band has indeed since signed with an independent label (Secretly Canadian/Dead Oceans) and news about their forthcoming debut album will come later this month.

With such a raging attitude towards major record labels, and with the band having previously made the odd jibe and prod at other guitar bands, I ask if they view themselves as something of an antidote to something they consider is culturally stagnant in contemporary guitar music? “I think what’s an issue in contemporary guitar music is that a lot of it is completely innocuous and there’s nothing challenging about it,” Green fires back in an instant.

“We’re not an antidote,” says Steen. “We’re a statement that can be interpreted as a joke.”

“We’re the disease,” Finerty throws in with humour.

However, another run-your-mouth-off-band Shame are not, with Forbes going so far as to say: “I don’t want to presume that we’re better than other bands.”

“Obviously there are some vacuous industry machine bands like the Hunna,” adds Finerty, “who are just like this sponsored thing created for kids that have lapped it up. So we aren’t that but I don’t want to slag off a band that I think are shit just because I think they’re shit.” Forbes reinforces this point too: “We always vocalise when we love a band and I think going out of your way to slag someone off just because you don’t like them is pointless.”

The real issue for Shame is not necessarily the quality of the music a group makes but their refusal to get behind the position they are in to speak up. This is something Green tells me when he says: “There’s nothing worse than seeing a band that go out of their way just to slag off people that are pretty much in the same boat as them, but, then again, if they are using their influence irresponsibly, that’s a different story. If they have a platform and they’re not doing anything [about social and political issues] then I find that shit, really.”

Are bands duty-bound to use their platform in this way, I ask.

“Bands have an obligation,” says Finerty. “There’s a key difference between taste in music and a political stance. If you’re promoting something that you believe is for the greater good and benefits the people of this country then that is a good thing to promote, whereas slagging bands is something else.” This is an area that audibly frustrates Green. “If you have an idea you want to promote and you think that is something that other people could benefit from then I think it’s irresponsible to not use it.” Likewise, Forbes comes alive on this subject too. “I don’t give a fuck about the sort of music a band plays if they are saying good stuff. I mean, Wolf Alice, for example, are not really my cup of tea but they are really vocal with their politics and it’s like fucking fair enough, man, you’re a massive band. We all have beliefs, we all feel something and we want change for this country – so why not use it?”

Whilst Shame are keen not to get into unnecessary wars of words with other bands, the day before we meet they did share an amusing aside with our photographer Dan about their time playing with a major label band – their worst touring experience to date. Four dates in they were asked to tone down their performances and asked to sign a contract prohibiting Steen from crowd interaction and having water on stage (he has a tendency to swig beer or water and fire it back into the audience). Presumably this was a bid to restrict the energy of the band’s performance, for risk of them overshadowing the headline act. Shame were also billed for a microphone after it made its way down Steen’s trousers.

For the band however, it’s not about upstaging or competing with other groups. They actually seem to live for the thrill of pure entertainment. “When we started we were playing to a few people and there was just a real humour to taking your top off and covering yourself in beer to just, like, two people who were on a date,” Steen says. “So we just treat it in the same respect but now there’s more people there.” Finerty thrives from simply giving the audience a ride: he almost seems eager to please in that sense. “I always worry people presume we’re going to think we’re bigger or better than them – that we’re going to look down on them because of how we are on stage. But you’re just trying to entertain people and have fun.”

That said, for Steen, he wants to see some action on that stage itself.

“You go and watch bands who stare at their pedals and it’s like why would you ever do that? This is first and foremost entertainment, you’re here to entertain people, you don’t have to degrade yourself to do it but don’t fucking ponce yourself up and pretend to be a superstar, just be yourself. Do something that people are going to enjoy and don’t think that you’re ever above anyone else because that’s the worst possible way you could treat what we do.”

Once again we’re back to the idea of preconceptions and the image people may have of Shame, which Finerty elaborates on. “I think some people just generally think we’re arseholes. Which I can understand. Maybe if you see Steen on stage you’re not thinking, ‘oh, I’ll go and say hello to him,’ you’re thinking, ‘oh he might glass me.’”

The group have taken the plunge, sidestepped university and thrown themselves into Shame. “We played 47 festivals this year – there’s no way any boss is giving you that amount of time off,” Steen says. Ultimately though, the group feel incredibly lucky to have had a place where they could practice for free and that they have their parents houses to stay at in the capital when they return from the endless touring. They are all too aware that London is changing and becoming inhospitable to many people and contemporaries wishing to do similar things. “We were the most fortunate band because we had access to the Queen’s, whereas any other band in London, how can you do it?” says Steen. “We never had that experience and we wouldn’t have been able to do it based on rates at practice spaces.”

“It’s absolutely unbelievable how expensive it is to live in London,” says Forbes. “The amount of money you have to be making even to get a foot up on the property ladder it is absolutely criminal. People are also now being ousted from communities that they’ve lived in for generations.”

The group’s relationship with the city that so clearly makes up a huge part of their identity is a love/hate one. As Steen says: “We’re lucky – people coming into London aren’t having access to the same opportunities we’ve had. You’re supposed to be presented with all these opportunities moving to London as a musician but the reality is quite a bit different. We don’t have any fucking solutions though, do we?”

“We do balance out the luck and the unfortunate quite well, though,” counters Coyle-Smith. “Today we smashed our van wing mirror,” he says, jokingly.

Finerty chips in that this is not a unique occurrence: “We’ve had many van-based cock ups. I think someone in the sky traded us some luck for some van curses.” Yesterday, for example, the group had to spend an hour with a wire coat hanger fishing for lost keys down the gap in the front seats. This was the result of an all-nighter in which the group had a lock-in at a pub in Bristol that kept them up until 10am.

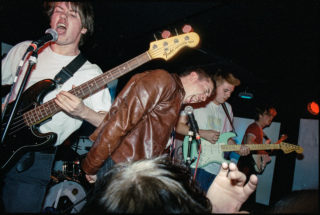

The table slowly turns into nothing but cans. Shame share a joint or two and leave to perform. As is now seemingly customary for their shows, it’s a lacerating, bracing and charging performance – one driven by the thrust of guitars that crunch against one another as distorted bass rattles the walls and drums crack like thunder, Steen pacing back and forth, slowly stripping from his fake red leather Firetrap jacket into a sweat-soaked naked body. Like a burst of bright white light, a combustion, a clattering of particles, the show feels over in an instant. Finerty hits the deck hard after slipping on the floor of beer and sweat but still beams from ear-to-ear in a clear instance of a group who look completely alive and full of purpose when on stage and having the force of their own creation bursting through the speakers.

As the sweat dries, breaths are caught and clothes are put back on, and Steen reflects on the role and importance of a live show and how it’s really not even about the group themselves – for Shame, it’s something bigger and wider than that. “I think one of the main things we try and get out of our live gigs goes back to our time at the Queen’s,” he tells me, “where it was such a sense of community. Where everyone is involved in one moment together instead of all the attention being on a select group of people.” Creating a judgment-free environment for music that was born in a judgment-free environment? “Yeah, exactly” he enthusiastically concurs, “but just write that I said that.”