Slint’s David Pajo is ready to finally draw a line under seminal cult album ‘Spiderland’

In 1991, Kentucky band Slint released an album that many now consider year zero for post rock

In 1991, Kentucky band Slint released an album that many now consider year zero for post rock

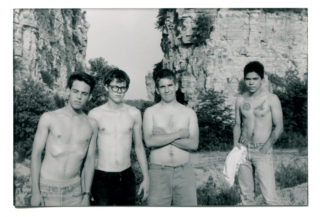

The idea of Slint being some kind of mythical beast rising from the eerie black depths of musical obscurity seems a ludicrous concept in 2014, as they enter their ninth year of reformation. However, there was a period during the ’90s in which the black and white image of four bobbing heads poking out of some Kentucky quarry water – as found on the cover of Slint’s second album ‘Spiderland’, photographed by Will Oldham – was all people had to go on in terms of getting to know the band. The motionless presence of the photographed four submerged in water also represented the motion and status of their musical activity, as Slint, at the time. Released in March 1991 and put out by Touch and Go, ‘Spiderland’ was a release that had no band around to play or to promote it. The group had already disbanded in December 1990.

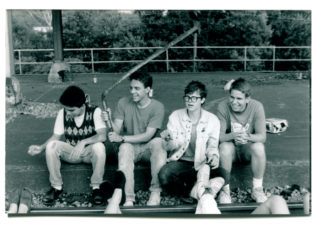

As kids they grew up in Louisville, Kentucky on an untypical diet of punk-rock and U.S hardcore, all members playing in teenage bands (primarily Squirrel Bait and Maurice, amongst others). Slint formed in 1986 with the line-up of Brian McMahan, Ethan Buckler, Britt Walford and David Pajo and in 1987 began recording their debut album, ‘Tweez’, with Steve Albini in Chicago. Entirely funded by friend Jennifer Hartman, it was put out on her own label (Jennifer Hartman Records) some two years later in 1989 and fizzled into the murky, obscurity-shaped hole it was destined to head into. Bassist Ethan Buckler disliked what Steve Albini had done with the record so much that he left the band as a result, soon to be replaced by Todd Brashear.

‘Tweez’ is a metallic, buckling crunch of an album; a cut-up-esque stitch job that resembles something mutant-like being formed and welded together in a studio with Dr Frankenstein Albini laughing manically as he turns something that once showed signs of form, structure and coherence into a seething, raging, brilliant mess. It’s an album that simultaneously captures the energy, range of ideas and the naivety of young men making their first album proper together with a producer who’s also in possession of all those characteristics. While ‘Spiderland’ is often held-up as the magnum opus of Slint’s short-lived career, the aggressively experimental, obnoxious thrust of ‘Tweez’ is perhaps greatly overlooked. It is ‘Spiderland’’s bastard offspring: troublesome, exhausting and occasionally difficult (rumours are neither confirmed nor denied that the album contains recordings of members defecating, which were then used as atmospheric interludes) but there’s still a lot to love – Touch and Go’s Corey Rusk certainly felt so anyway as he then signed the band.

The upcoming documentary on Slint, Breadcrumb Trail, opens with the Hunter S. Thompson quote, “Just keep in mind for the next few days that we’re in Louisville, Kentucky. Not London. Not even New York. This is a weird place.” It sets the tone for a documentary and back-story that seems to place a lot of emphasis on the strange place the group comes from. I speak with David Pajo, who sets the scene. “One of the quotes that I found interesting [in the documentary] was when Ian McKaye (of Minor Threat, Fugazi) said that Louisville has this reputation that everyone there is just totally crazy, and that is a wide-spread view that I wasn’t aware of until I moved to Chicago in the mid ’90s. Then from touring, I then realised that Louisville has this reputation of being filled with people who are out of their minds and I think that’s fairly accurate to be honest, and growing up I just assumed everyone was crazy. Like the singer from Maurice, the band that was a precursor to Slint, like even when we were young he was getting checks from the government for being mentally insane and he wasn’t the only one. I had so many friends that had them – we call them ‘crazy checks’ – and I knew so many people that were getting them and even some of the people in the documentary are considered… like… have been in and out of institutions, and some of them have even passed away since the documentary. So, I didn’t have any objective view, I just thought that was the way it was, but when I left Louisville I realised that this isn’t a normal way of growing up.”

The group, while often given the ‘mysterious’ tag, were in fact like most young men in a band – they were daft, told jokes and pulled a lot of pranks. “It’s always been encouraged in Louisville, like the weirder the better,” Pajo tells me. “That’s not to say the entire city is like that, just in this music subculture it was almost like a badge of honour.”

The documentary – which is being released alongside a mammoth ‘Spiderland’ vinyl and CD boxset this month, complete with 100+ page photo booklet with a written introduction from friend and collaborator Will Oldham – is filled with such jokes and pranks that vary from the terrifying to the disgusting: turning up at Steve Albini’s house (having never met him) with a shotgun pointed at his face when he opened the door, to taking a revenge shit into Jesus Lizard singer David Yow’s drink.

Before embarking on ‘Spiderland’, this time with producer Brian Paulson, Slint would record a two-song E.P, again with Albini as someone pulled out of a booked studio session last minute, but this was not released until 1994. Did this irk Albini, who was/is a big fan of the band, not to be asked back? “I did think about that when we were recording it, but we had already chosen Brian Paulson,” says Pajo. “I think Jesus Lizard were recording ‘Goat’ almost at exactly the same time as ‘Spiderland’ and they all showed up at the studio to see if we wanted to get dinner with them and I remember Steve walking around checking out the microphone placement and the studio and I got the feeling back then that he was a little bit pissed off at us, and we didn’t go to dinner with them because we were busy! But it wasn’t out of any lack of respect for Steve’s abilities or anything, we just wanted to work with someone else. Brian Paulson had done the Bastro record and Brian [McMahan] really liked some of the sounds he was getting for that. So, yeah I did get the impression Steve was off with us but we did record the 10” with him.”

The band broke up before releasing ‘Spiderland’ under a set of circumstances still unclear. Temporary admissions to psychiatric hospitals, poor time management, commitment issues are all said to be somewhat contributing factors, but there was no real drama, no real story and scandal to be unearthed from the split, and in fact the group all remained active together, just in different incarnations. “We still continued to play with the same group of people but it was in Will Oldham’s band or with King Kong,” says Pajo, who feels the break from Slint has perhaps aided the band’s reputation in the long-run. “For us, we were still doing our thing but I think the fact that there was so little information and so little promotion – no tour, no marketing, the record just existed by word of mouth – I think it did benefit us in the long-run because it created a mystique that we didn’t intend; we weren’t trying to be a mysterious band but we became that by default.”

The spreading reputation was understandable; the results of ‘Spiderland’ were unique. It’s a release that is equally as unsettling and vicious as it is pastoral and pensive. It’s a record that many attribute to moulding the Post-Rock template, the slow/fast, quiet/loud, moody/explosive dynamic, but there was much more than teasing anticipation and rocketing paroxysms to the record. ‘Spiderland’ shifts in floating waves. It shuffles and shatters in syncopated cadences and the sound of malfunctioning guitars screech, wail and howl in agonised union and discordance. The vocals introduce a narrative and fleeting sense of comfort and structure amidst all the rupturing chaos. It’s a record that takes on the image of sitting on a back porch on a rocking chair in the quiet night of Kentucky while crickets paint the breeze with a hypnotic and calming chirp, only for a chainsaw-wielding madman to burst through your garden fence with a murderous glint in his eyes and primal roar tearing his vocal cords to shreds. It’s a mere six-songs long but now, even in 2014 after it’s reached the status and exposure it has, it sounds timeless, taut and punchy. Pajo concurs: “I always feel like Slint was thought of as a band of the ’90s but we broke up at the beginning of the 90’s and most of the songs were written in 1989 and early ’90, so I kind of feel like more of an ’80s band but I’m glad that we chose to do the production in a way that was a more purist, documentary approach, just a band in a room. I think that lends itself to not becoming dated, it doesn’t sound like an ’80s production or even a ’90s mainstream grunge production. It’s more natural.”

While ‘Spiderland’ grew in mystery, word-of-mouth, steady sales and reputation through the early years of the ’90s after its release, so too did Slint’s mailbag. The reverse of the album cover printed an address and a public call for female singers for the group – a snapshot of what future Slint may have sounded like should they have continued – and they received many responses. One letter allegedly came from PJ Harvey, a rumour that turns out to be entirely true. “We didn’t really go into it too much in the documentary,” says Pajo. “We were going to re-print the letter she sent us in the photo book as it was really cool but we asked her first if it was okay and she said it was a personal letter and she would prefer it if we didn’t, so out of respect for her we didn’t want to talk about that too much.

“After we broke up, because Britt’s address was on the record, he started getting a lot of mail and it all just went into a cardboard box that we never looked at for years, and one time I went over to his house and we started going through these letters and we started opening them and some people had sent money for ‘Tweez’ from, like, Poland or somewhere, but it was three years old at the time or something, and then we found this letter from PJ Harvey and I don’t think she had put out any records yet but there was a big poster of a picture she had taken with her guitar and she wrote in there that she’d had some difficult times in her life and all she could listen to for a long time was Howlin’ Wolf and ‘Spiderland’ and she asked if she could be our singer, but we didn’t see this until much later, but we wrote her and thanked her for that letter.”

In the years in-between breaking-up and getting back together, Slint’s band members have all been involved in multiple projects. Pajo has recorded extensively as a solo artist and also been in Tortoise, Interpol, Royal Trux, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Zwan and many others. Britt Walford played a pivotal role in shaping the sound of the Breeders’ ‘Pod’ album as well as various other, often mysterious or un-credited roles in other bands and projects. He was also in bandmate Brian McMahan’s project, The For Carnation (whose eponymous record is an often overlooked gem) and Todd Brashear has been a long-time Bonnie Prince Billy contributor.

While the group didn’t reform until 2005, it was as early as 1993 that they began to get a feeling that their reputation and music was growing. “I was working a day-job and hating it, all I really wanted to do was play music,” says Pajo. “I realised that I was making more money from record royalties than I was from my shitty day job, so I just thought if this is what I want to do then I should do this all the time. It wasn’t that I made a career choice, it was by default, it just made sense. I thought it [‘Spiderland’] would taper off and disappear into the void for a while but it was pretty interesting to see the events that came afterwards. Unlikely sources where starting to reference Slint – I remember Mogwai did a David Holmes remix using the ‘Good Morning, Captain’ riff and Harmony Karine picked out the same song for the Kids soundtrack; it was really surprising that that record didn’t get lost in the shuffle.”

The mushrooming reputation and classic status that ‘Spiderland’ has attained has in fact changed Pajo’s own feelings towards the record. He says: “It’s definitely changed my perception of ‘Spiderland’. Pretty much throughout all of the ’90s I could barely even listen to the record, not that I hated it so much, it’s just all I ever heard were mistakes and things I wanted to change and how I wish we had more time in the studio and a better budget to make the album. Now I can appreciate it for what it is and look back in hindsight and think for a group of young kids from out in the middle of nowhere, we didn’t do too bad of a job. I can appreciate it now.”

One question this boxset does raise, along with the near decade-long reformed status of Slint, is that perhaps ‘Spiderland’ is now ready to be put to bed and left to rest. “I have a feeling that by the end of this year we will have closed that chapter, which I’m happy to do. I have felt that musically I’ve lived in the shadow of Slint, and that’s not a bad place to be, but I would like to move on from the songs on ‘Spiderland’.” says Pajo ahead of the group’s 2014 dates, including Primavera Sound.

“We have talked about new material,” says Pajo. “I think there is no shortage of song ideas; I think we just want to get through this year and see where we are afterwards. There has been no commitment to start working on a new record or release new songs.”

I ask Pajo if the success and reputation of ‘Spiderland’ has, in some sense, become too big to control? Too much of a monster that makes it a difficult, even fearful, record to move on from? “I’ve definitely brought it up with the other guys,” he says. “I know that we will never make another ‘Spiderland’ and I don’t think that we should – we did that when we were younger and in a different emotional state. Brian particularly, lyrically, his contribution to the record, he made himself really vulnerable in a way that I don’t know if he would want to again and I would never ask him. I think we would make a cool record and it would be compelling but it wouldn’t be– and I hope no one expects it to be – ‘Spiderland’.