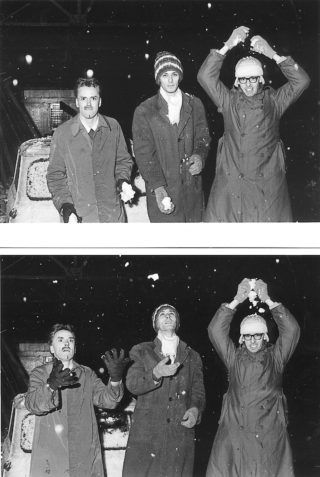

Three Men in A Fridge: The Story of This Heat

Confounding genres and eschewing labels – Retelling the story of This Heat

Confounding genres and eschewing labels – Retelling the story of This Heat

There are some bands that seem born to confound genres and eschew labels and then there are others that seem to exist as a very means to destroy them altogether. The latter is an attribute most certainly applicable to the inimitable This Heat.

The band were a trio who were originally active between 1976-1982, consisting of Charles Hayward, Charles Bullen and Gareth Williams. Hayward was primarily a drummer, having played in groups before, most notably Quiet Sun, who disbanded in 1972 with their guitarist, Phil Manzanera, going on to join Roxy Music. Hayward put an advert in Melody Maker (“I think some of the words used might have been ‘wasteland’ ‘mutant’ and ‘aqualung’,” he reckons) and Bullen responded, turning up for an audition at Hayward’s parents’ house in Camberwell. “It was a tiny room with egg boxes on the wall,” says Bullen, “one he used as a drum rehearsal room – it was about six foot square and we just squeezed in an amp and a person.”

Despite a number of reputable musicians turning up, including David Toop, Percy Jones and John Etheridge, Hayward gravitated towards Bullen’s unique style of playing.

“Charles could play very hard and fast,” remembers Hayward, “but he would use an effect and make it feel like it was coming in from miles away. The sound would then feel like it was getting nearer because he was using a swirl peddle.”

The pair continued as a two piece for some time, experimenting and pushing the limits of their number, until they realised they were not quite complete as a duo. They brought in Gareth Williams, who was a complete non-musician. “Gareth had big ears,” Hayward says, “which was more important than his abilities as a musician.” This Heat was born and the combination of Bullen’s and Hayward’s profound musical ability and shared vision of experimentation, and William’s non-musician presence, solidified a truly unique export; one that challenged the conventional structures and approaches of music in the 1970s, often because one of their members simply didn’t understand them. “One of the most effective things about working with Gareth was that he just didn’t know,” recalls Hayward, “so he questioned everything.”

The birth of the group also bore a concept in many ways, too, as Hayward tells me: “It was this idea of all channels open, so not about just tuning into a song or tuning into what would be some sort of music concrete or electronics or tuning into free improvisation or sound art or rock. It was none of these things because it was all of these things. So you didn’t ever confine the group, you let it be what it wanted to be.”

“This Heat was formed from the collective desire of its individual members not to be in other people’s groups,” says Bullen. The idea was that everyone was equal in This Heat – all roles as important as each other; this was not somebody’s band that other people played a part in, it was a collective output.

The group found a home for their improvisations and experimentations in an old meat factory in Brixton, setting up in what was a disused cold storage room. The room-come-studio was named, fittingly, Cold Storage.

“It was an old industrial space that was earmarked for demolition at some point in the future but there wasn’t going to be any money for it for a good few years,” remembers Bullen. “So it was leased out by its owners to Acme galleries, who were an artist collective, and the place became filled mostly with visual artists. The actual cold storage room that we used had no windows, big thick metal doors on it, a low ceiling with metal zinc sheeting on the walls – it wasn’t really any use to visual artists because there was no natural light. When we moved in there was no air in there so we had to pull off one of the sheets and hired a kango hammer and drilled a hole in the wall, just to get some air in it.”

Here the group toyed with tape loops, billowing drones, eerie echoes and a continuation of generally sideways approaches to the use of guitar, bass, drums, vocals and keyboards, resulting in a sound that seemed to somehow construct the foundations for post-punk whilst also pulling them apart. A fog of ominous doom may hang over some of their recorded content in tone but a sense of fury and violence was something Hayward was trying to channel when approaching their work. “There was a need to acknowledge that there is a violent streak in the world and probably inside all of us and that it’s one of culture’s functions to control that. I used to be really emboldened by The Who, that they dared to sound like that and be that aggressive with sound. It was like how I imagine going to see some primitive ritual would have been. There was a lot of po-faced jazz rock going on at the time, with people taking their instruments very seriously – including me and I still do – but people were getting caught up in the niceties of doing it and playing it, nobody was painting any nice pictures or making any journeys. It was just very well played music… you want to go down the road that lets you be good at your instrument but you can also be trapped by being good at your instrument.”

Essentially, this was a group anticipating and constructing the formula of punk but presenting it in a style that already seemed bored of the primitive growl of punk before it had even really been heard. Bullen recalls being excited by the prospect of such a movement but less so with the reality. “I remember reading about this scene in NME in 1977, about people singing lines like ‘no more Rolling Stones’ and we were thinking, great, imagining some sort of musical revolution was coming, but then when we heard this purported revolution, we were like urgggh, just sounds a bit like the Rolling Stones. Although at least they weren’t singing in fake American accents like Jagger.”

Looking at the group’s output retrospectively, they stick out like jagged nails in a wall, but this was something the band were more than aware of at the time, too. “That was sort of self evident but at the same time we tried to maintain a sense of connection with other musicians… just not so much with trying to be like them,” Hayward reflects, with Bullen adding: “We knew we were out on a limb but on the other hand we were quite arrogant… maybe arrogant is too strong a word but we were quite sure of ourselves – we knew we were doing something specific. Most of the early gigs we promoted ourselves and were small, arty, London gigs. Later on we did get lumped on stage with random rockier bands, then later still we did end up on the bill with some bands we felt a sense of solidarity with such as 23 Skidoo or the Pop Group or the Slits, especially by the time of the second album [‘Deceit’] when we were on Rough Trade as there was definitely more of a scene around that label.”

The Pop Group’s Mark Stewart was so emphatic after seeing This Heat that he proclaimed he would give them half of the £1 million record contract they thought they were just about to sign. “They still owe us that,” says Hayward.

The group were something of a template band for John Peel’s tastes around that period, too, and arguably his whole life: noisy, freaky, new-fangled, peculiar and exciting, a seething ball of indefinable fury coming from god knows where. A fridge in Brixton, it turned out. The sessions that This Heat did for Peel really are some of the finest recorded and this is something Bullen recalls doing with glee. “We sent in our demo and then I phoned John Walters [session producer] once a week asking if he’d listened to it and then he eventually gave us our session. That was a great thing for us. I’d grown up and been radicalised and turned onto music by John Peel for years before. It was great when he gave us a session. We did two in ’77 within a few months of one another, which was a bit unusual and I guess showed how much he loved the first one, but I think he found our second one a bit self indulgent and didn’t offer us another one after that.”

The primary reason I am speaking with the pair today is because This Heat are back. Sort of. They play a two-night residency in February at Café Oto under the guise of This is Not This Heat (with more offers of future shows coming in as we speak), which technically is true as Gareth Williams passed away in 2002. Instead, the band have taken on the services of some new members, including Thurston Moore and Daniel O’Sullivan. The occasion ties in with the reissues of their recorded output via Light in the Attic Records, and marks 40 years to the month that they played their first ever gig, which Bullen recalls as having “a small audience but interested and appreciative.”

Hayward remembers it being about three weeks after Williams had first picked up an instrument. “We had a few ideas put together but not very much,” he says. “We had a skeleton to hang improvisation on. We didn’t really know what the group was. Later on things got a lot more fraught and I would get stage fright… well, not quite like that, it wasn’t that I didn’t want to go on stage but that I was scared of letting the music down. Later on I would be walking around in this pre-gig state for eight or nine weeks, which was like fucking hell. The first one wasn’t like that at all, it was more like bloody hell I’m on stage with Charles and Gareth!”

Looking back at This Heat now, it seems like attempting to place any kind of even vague descriptor on them is as difficult as ever, if not more. “I hate genre,” says Bullen.

“What I’m into is trans-categorical music, which I think is what This Heat did.” He’s fairly clear on what he wants the band not to be called, though.

“One classification I hate – and always have – is industrial. It seems to have died out now but a lot of people used to throw us in with Throbbing Gristle or whatever and that really annoyed me.”

Forty years since their first gig and thirty-four since they broke up, Bullen admits he’s finding it strange to be working through these songs again. “My initial thought on getting back together was ‘oh shit’ but then if not now, when?” he says.

Hayward has had some bizarre moments in re-connecting too.

“History repeats itself, so instead of singing about a loop that you saw your father and grandfather go through, suddenly you’re singing about a loop that you’ve gone through. It’s very, very, very, very weird, Dan, it’s a fucking weird one,” he says with real emphasis. “You’re singing about something observed but then you’re singing about something experienced… this last couple of weeks it has been like relating a song about a loop to my own life.” He lets out a maniacal laugh that is almost comic-book super-villain, clearly lost for a moment in the oddity that he’s living in a conceptual musical sphere he shaped decades ago. “The whole theory of the thing being an object is gone – it’s no longer an object it’s a natural lifespan. It’s blown my fucking mind. Although I say let the irony of the material being performed today do its work. ‘Twilight Furniture’ was about a surveillance society, it was about cameras everywhere, it was about having your mind shaped by what you were told. ‘Escaping Gas’ is about getting the things you deserve, a nation votes and it gets the politicians it votes for, so your air is also your vote – it’s what you breathe.”

“That’s another loop, another spiral,” he says. “It’s like I’ve met this 25 year-old drummer, and I’ve been trying to learn his parts and this guy is whacked, he’s a whacked young man in a very extreme place.”

Re-visiting the group’s material and their influence becomes indisputable. It can be heard echoing all the way from the early guitar clangs of Sonic Youth, right the way through to contemporary groups such as Viet Cong whose wiry prang and pummelling drums are projected from the forces the band ignited so many years ago.

Despite This Heat being deeply thoughtful, conceptual and experimental the reason they have succeeded in acquiring such cult longevity is because they still hit on a base level. They have gut-busting guitars and deeply rhythmic songs; they assault and impact the body whilst tickling the mind and a great deal of their music is as physical and overcoming as it is intellectually rewarding. Such is that sense of overcoming power going back to these songs again that Hayward himself has been bowled over by their force. “I burst into tears after one song. It feels so beautiful to be making this music.”

A small but perfectly formed catalogue re-issued

This Heat (1979)

Heavy on tape loop experimentation, as found on tracks such as ‘24 Track Loop’, for every eerie clang and ghostly what’s-in-the-basement? clatter there is the blistering force of tracks like ‘Horizontal Hold’, which sounds like a helicopter taking off in the middle of a battlefield. It’s a lean record: tight, muscular and forceful, dry and sparse in tone but rich in its experimental depths. There’s a lurking sense of paranoia that floats over the record like an unwelcome apparition. The influence of the Canterbury Scene – particularly Robert Wyatt – can still be detected, too, but ‘This Heat’ is an album of a band very much forging its own personality.

Health and Efficiency (1980)

A two-track, twenty-minute EP that contains the group’s most pop-leaning moment in the exquisite title track. It’s probably the band’s finest moment, simply because they manage to do so much with so little, and yet whilst ‘Health and Efficiency’ may be two tracks long, they are ones teeming with propulsion, ambition and oceanic levels of depth. The title track charges with gusto and Hayward’s drumming is frenzied in its rattling attacking but also joyfully restrained. This EP is a band playing with their palate. ‘Graphic/Varispeed’ is a cinematic in scope piece of ambient static, the eerie whirl of the tape feeling like an uncoiling anxiety attack.

Deceit (1981)

More paranoia here but this time perhaps more realised, with the fear of nuclear war acting as the sonic mushroom cloud. It’s a more complete, denser and varied record than ‘This Heat’, opening with the lullaby-esque ‘Sleep’, which is as beguiling as it is bewildering, and a truly unique opening to an album. It plants you into a world that already exists, no introduction, straight in there. If anything, you feel like you’ve arrived at the end of something – perhaps precisely being the point of nailing that nuclear level fear. Terrifying, utterly odd and sublimely original, it still sounds like nothing else.