On my favourite track, ‘Riding Cobbles’, Savage duets with drummer Dylan Hadley on a rhythmic, whimsical composition that feels almost satirical in the context of flaming end times. But the album is infused with a sense of childish wonder too; a collection of maudlin nursery rhymes (and I mean that in a good way), which hint at the possibilities still available in a ruined future. I wonder how far this jarring composition reflects Savage’s own apprehension about life in New York, that paradox of excitement and trepidation about leaving the familiar for something new; the optimistic naivety that has to accompany that. Was a sense of shifting place, and the anticipation of a new life, channelled deliberately in the music?

“Sure,” he says, dipping a flatbread in some hummus he’s just ordered. Most of the tracks, he tells me, were written in New York, but always in the knowledge he was leaving. “I think every artist has a relationship to the place that they live or call home. So I think the artist is always sort of grappling with their identity and location, home, geography. And that’s a really key part of the way we identify ourselves. So it makes sense that, you know… I mentioned [James] Joyce in one of the songs, ‘Elvis in the Army’. It sounds a bit lofty, I guess, but I do think it is interesting that he, you know, for most of his professional career as a writer, did not live in Dublin, yet focused on writing about it. And there’s always … I’ll always be from America. I don’t call [Paris] home because at the age that I’ve moved here it doesn’t feel right to call it that. New York has got me still – home. That’s where I came to be who I am.”

So why leave? I ask – the album doesn’t necessarily give the impression that was a straightforward decision. And we’re back to the end times discussion. “I felt like I had to go somewhere. I’m 36 and quite scared of what’s happening in the US. You might think, ‘Well, then why did you go to France?’ Because they have very similar problems here, actually. But I had to go somewhere. I knew that I had to leave. I had to go somewhere. So I’m not sure if I’m going to stay here. I think that is important to note. I don’t know where I’m going to go, but I had to go somewhere, and I started here because I’ve got the most friends here as anywhere in Europe. And being in the EU seems important to me – and the record label [Rough Trade] is here. I want to be somewhere where I have access to healthcare. That’s important to me. And I would like to be somewhere that isn’t as violent, where violence isn’t so much a part of your daily consciousness like it is in the States. But it’s… I don’t know. There’s a certain amount of hopelessness I think, that’s starting to permeate the American identity. And I was feeling that. And I didn’t like it. And so, you know, I’m still figuring out the exit strategy.”

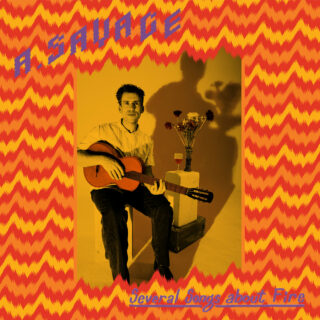

I order one of those perfect folded Parisian omelettes as Savage speaks. What’s fascinating in talking to him about his work is the contrast between his slightly awkward personal demeanour and the confidence of the delivery and craft of his music. On Several Songs About Fire, Savage doesn’t only do the atmospheric work of conveying an internal and external world in disarray; another remarkable feature of the album is the lyrical wit and wordplay. At a technical level, the words deliver a conviction that suggests an artist fully realised in his chosen medium – Savage sees this ability with words as a cornerstone of his artistry and part of the musical legacy from which his practice has evolved.

I order one of those perfect folded Parisian omelettes as Savage speaks. What’s fascinating in talking to him about his work is the contrast between his slightly awkward personal demeanour and the confidence of the delivery and craft of his music. On Several Songs About Fire, Savage doesn’t only do the atmospheric work of conveying an internal and external world in disarray; another remarkable feature of the album is the lyrical wit and wordplay. At a technical level, the words deliver a conviction that suggests an artist fully realised in his chosen medium – Savage sees this ability with words as a cornerstone of his artistry and part of the musical legacy from which his practice has evolved.

“I guess the first thing I was attracted to [as a consumer of music] was probably just like a clever turn of phrase,” he says. “And I mean, obviously, like all the British Invasion bands were pretty good at that. The Kinks were really good at it; The Beatles certainly were. And then I think, you know, I got into punk because it felt righteous and it had a message and it had something to say. And that’s an important part of being a lyricist, is that you feel strongly about something and have something to say. I think. So, I guess I kind of learned that lesson. And then, you know it’s a lot of the usual suspects for [influential] lyricists, I think. Patti Smith. Television. Dylan. But also, I’m originally from Texas and I grew up hearing a lot of country music, which is a very narrative type of music and is kind of based in storytelling. And so. Yeah, there would be people like Townes Van Zandt and Neil Harris.”

It’s his lyrics, he tells me, that resonate most with fans, who understand that he has something to say and a specific way of saying it. That is not just in the specifics of the words, but in the way the words translate off the page. As he warms into discussing the process, Savage reflects on the ways he has developed as a singer, now able to use technique to control the delivery of his words.

“I mean, I guess with every record I challenge myself in some way,” he says. “You know, I try to play with range a bit. I like the line between singing and speaking. There’s a line between singing and speaking and playing with that is interesting, I think. Some people we describe as having a melodic voice or a singing voice. No one would describe me like that. I know this, I kind of have a monotonous voice, I know, but not when I sing. When I sing, I can do a lot of different things. I like that line between talking and singing because it involves subtlety, which is important. There are some people who can just get out there and belt, and I can do a bit of that. I can project my voice quite loud, but that’s what I like – I like playing with dynamics, as far as being a singer goes. And I guess with the work that I make under my own name, A Savage, it’s maybe bit different. Maybe that’s one of the ways it’s a bit different. I just use my voice in a different way. I don’t know how familiar you are with Parquet Courts, but it seems to me like it’s pretty different.”