Ten years of, Daniel Kessler revisit’s Interpol’s ‘Turn On The Bright Lights’

There is a light...

There is a light...

Few bands ever truly go the distance. It’s a cold hard fact of growing up obsessing about, falling in love with, and endlessly discussing the demise of your music heroes as they burn out in a blaze of misguided ambition, stubbornly fade into obscurity or painfully evolve into Bono. And while they rarely defy the corrosion of tastes, trends and time for too long, albums typically fare much better, often capturing bands at their most vital. But let’s not get this confused with wet-eyed, rose-tinted romanticism; the majority of bands and albums make perfect sense at the time but only some truly stand the test of it.

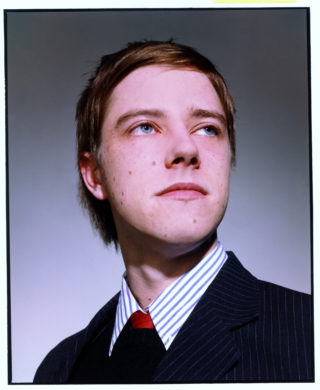

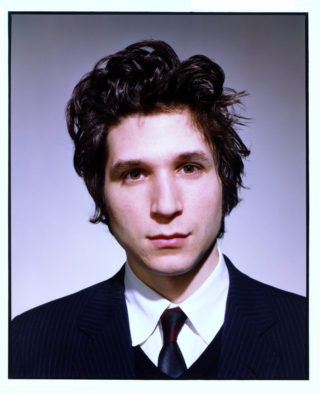

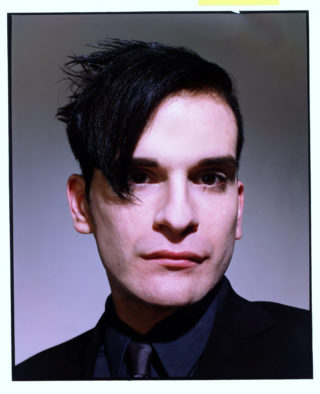

A decade after guitar music’s last great resurgence, Interpol’s monotone, monochrome introduction stands as aloof and lovelorn as ever with ‘Turn on the Bright Lights’ the immaculate calling card; as clean, sharp and effortlessly dark as Daniel Kessler, Paul Banks, Carlos Dengler and Sam Fogarino’s perfectly tailored suits. On August 20th, the album turned 10; next month, on December 3rd, it will receive a respectful, deluxe re-issue.

It’s one of the albums that’s characterised and crystallised that renaissance, while creating one of the most memorable band aesthetics of this generation: the clinical beauty, slow-burning intensity and dedication to a simple black and white image. But the music was anything but, melding the despondent weight of Banks’ penetrating lyrics with Kessler’s tumbling guitar melodies.

Looking back isn’t something Interpol have ever been comfortable with, but after promising to mark the ten year anniversary of their debut in the right way, they were aware that it demanded the same attention to detail as any of their other work.

“Once we committed to doing it, like with all our records, if we are going to say something, we really want to have something to say,” explains Kessler from a break in Italy. “And once you commit to doing it, you need to do it properly and spend a lot of time and energy digging through photographs that were never published and the rare tracks and the DVD footage.

“I remembered a recording of us was playing in New York City in the Mercury Lounge. I’m not really sure why we decided to record that show, but I think we needed it to send off to a festival or something. That was Sam’s first show and you’d think the first show might be something you’d throw away, but I remember it being a really good show and feeling really committed. I was looking back at it and I felt we were a really tight band and you could feel the chemistry. Now looking back through all this archival stuff, looking back with some objectivity, it’s pretty amazing to see how significant that show was all these years later.

Kessler notes that this is not an exercise in fishing for new fans with old material. “We’re not going to convince anyone now,” he says, ‘so this is more for the people who like the idea of an anniversary, commemorative edition record. We have really great fans and we thought they’d appreciate it and care about it.”

Loaded with rarities, demos and footage of that first gig with Sam, it’s a re-release done right, as well as for the right reasons. But as with any re-issue, there’s always a level of cynicism about the motivation behind it and something Kessler is up front about.

“I don’t think it is a way of making money, especially the way we’re doing it!” he exclaims. “The album version of it is really beautiful, it’s like a coffee table book and it’s quite limited. There’s much better ways to make money doing something like this but that’s not the route we’re taking. All of our discussions and our discussions with the label were about doing something nice.”

‘Turn On The Bright Lights’ is an album recorded to a backdrop of struggles, rejection and a very urban tale of surviving in the city. It’s one that carries and conjures memories, capturing the verve of NYC that, to those of us across the Atlantic, was emerging as the focal point for the guitar music that defined a generation.

“I think I would have done the same thing and romanticised it too, but for the most part,” admits Kessler who, although raised in the States, is an Englishman by birth. “I started hearing about all these bands when they started getting attention.

“New York’s obviously a huge city and there are a lot of bands who can co-exist without really being aware of each other, and I’m friends with a lot of those bands now, but friends in the way that you meet other bands touring in other cities. It wasn’t like the same building or the same rehearsals or anything. It’s a question people ask and I always wish I had a better answer.”

Five years of toughing it out in New York, battling against the label rejection and resolutely working to perfect and finesse the Interpol dynamic ultimately paid off.

After being turned down by “every record label in the world”, including Matador, who they eventually signed with, despite the struggle, Kessler clearly holds that period in fond regard.

“They’re incredible memories,” he reminisces. “We spent five years being rejected by every record label around and struggling to play gigs in New York City. It’s expensive to get by and most bands don’t make it that long in New York because people’s attention spans are pulled every which way, and it takes a lot of work to stay together.

“We had very simple dreams and ambitions, so when you finally get to do it after being rejected so many times, you relish the experience. Even Matador rejected us twice before signing us.”

There’s a conviction and vindication with Interpol that hasn’t dissipated in all these years. It’s an example of the strength of feeling and sacrifice that went into ‘Turn On

The Bright Lights’ and while the rags to recognition stories are well-trodden, it was the patience and dedication to perfection of the time that helped make the record as passionate and esteemed as it is now.

“Making the record, we all lived in the same house, fighting over the room with the best bed, battling the cabin fever of being so close together all the time,” laughs

Kessler. “It was an incredible process. We mixed the record one way and had a choice to put it out as it was or wait several months until the studio was free and amend the songs. It was difficult to wait but it was the right thing to do. Going back there the second time and working with Paul and fixing some of these tracks to make them better than the original mixes felt great.

“It’s a pretty painful process, in a great way. When you’re making a record and when you’re playing songs and they sound right, it doesn’t mean you’re going to capture that in a recording studio. You have such a small window to get it right, so there’s a lot of pressure and you don’t want to leave any regrets. There’s nothing worse than leaving the studio and wishing you’d gone another way. We’ve sacrificed a lot to never be in that position. Once you get it right and feel good about it, you have to let it go. We were so close to not letting that happen, but then it felt like we always intended it to.”

To many, the band’s debut was the benchmark; the albatross that would inevitably, gradually weigh Interpol down, like The Strokes’ ‘Is This It’. Blessed and cursed by a debut that was as essential then as it is now, Interpol’s subsequent albums undoubtedly haven’t scaled the same heights, but that doesn’t leave ‘… Bright Lights’ legacy any less diminished; it’s a defining reminder of the seminal catharsis and beautiful gloom Interpol seduced us with from the very start.

“We were always aware that with first and second records, you don’t want to take too much time,” says Kessler. “We were writing in between the Bright Lights tours and were very mindful of keeping the continuity going between the writing process and the touring. On ‘Our Love to Admire’ we took a very different approach artwork- wise with dioramas and the animals, and that’s always been symbolic of what we’ve always done as a band: it’s not about a career; it’s about what you want to say in that moment. There are no guidelines, but the truth is we are who we are to a degree – I do wear a black suit every day, it feels comfortable, it feels right. It actually feels like the simplest thing I could do, in a way.”

And yet, somehow there’s always been a gnawing sense that Interpol are a band that shouldn’t have emerged from the New York melting pot so successfully; that without that city spotlight, everyone else would have been scuttling in The Strokes’ commercial shadow. And after those years of painstaking toil, desperately searching for a collective alchemy, instilling an infinite loyalty in the group of hardcore fans who would ultimately drive the band forward, you understand why ‘Turn on the Bright Lights’ is so special.

In 2002, it was the passionate absolution for a band determined to make it work; the statement of proof they’d make it, whatever it took. Now, it’s just how Interpol want it to be: a love letter to the fans that got them here in the first place.

“I think it [the album] just set everything in motion,” Kessler muses. “I appreciate the sport of discussing music, but the first time you hear something, there’s only one first time. I did that a million times over but for me I’ve never looked back at what we just did and compared it to what we might do or could do.

“It’s always been an organic thing for us and we either felt it or we didn’t. I think if we’d had those kind of discussions, we wouldn’t have gotten very far. It was always a case of, ‘Are we into what’s happening in this room or are we not’ If we are, then it moves forward, if we’re not, it comes to a standstill. We’ve always kept it that simple and fortunately we’ve always had enough to inspire and motivate us to go in different directions. I wouldn’t want to sit there and try and do something we already did.

“Artistically I’m always excited about what the next record will do and we’ve never looked at this from the point of view of ‘this didn’t work, we’ll try this’. I think if we did, we’d be a very different band. It’s always been about what we have to say and I think we’ve always had enough to say.”