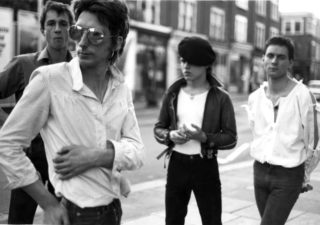

The story of Wire retold – a band facing forwards, celebrating 40 years without a nostalgia tour

"Wire is still the most famous group you've never heard of," says Colin Newman. "There's still a massive untapped world out there."

"Wire is still the most famous group you've never heard of," says Colin Newman. "There's still a massive untapped world out there."

On April 1st 1977 Wire played their first ever concert as their “classic” four-piece line-up (Colin Newman, Bruce Gilbert, Graham Lewis and Robert Gotobed) at the infamous Roxy Club in London’s Covent Garden. They shared a bill with The Cortinas, The Models and Buzzcocks. With songs rarely lasting beyond two-minutes they hurtled through an often Ramones-like set, but even on this very first outing the set was littered with moments of refined brilliance that would soon come to define them.

Intent on antagonistically breaking the norm from the off, they played tracks like the fantastically brooding ‘Lowdown’ and hammered out the infectious stabbing and melodic shuffle of ‘Strange’; songs that would have no doubt been deemed disgustingly slow and out of whack for the template formula of punk that was fast setting in around this period and within those club walls.

Most group’s first ever gigs are intent on winning over the world, a quiet nervousness in which being liked is secretly as important as being good. For Wire, that night they embarked on a career that has now lasted 40 years and in which winning the world over will only ever be done on their terms or not at all.

Almost 40 years to the day of that Roxy show, with album number 15 out this month, the group’s founder, singer and guitarist, Colin Newman, still steers the project in a direction permanently locked to forward, although is perhaps a little less superciliousness than those early days. “When we were in our twenties there was incredible arrogance,” he tells me. “There was no way that anybody in Wire didn’t think that we were the best band in the universe. That was a given.”

Across their three first albums ‘Pink Flag’ (1977), ‘Chairs Missing’ (1978) and ‘154’ (1979), though, there was genuine argument for them holding such a prestigious title. The sense of breadth, growth and experimentation across those records created within a mere 22 months remains a staggering feat in contemporary music. ‘Pink Flag’ harnessed the momentum of punk and purified it into a minimalist masterpiece; an album that would go on to influence the American hardcore movement in the 1980s just as potently as it would the American college rock and Britpop releases the following decade. ‘Chairs Missing’ retained the crispness of its predecessor but came loaded with textural and structural explorations that at times felt like such an evolution that it could be another band altogether – a record that simultaneously feels entirely genre-less whilst fundamentally creating a blueprint for one at the same time. ‘154’ emerged to be another beast altogether; a gloomy and murky piece of noir art pop-rock that was also radiant and often glistened.

By the end of all three albums the group’s craft for the intoxicatingly melodic and the bracingly challenging was uniform. They had created such an apex in those releases, and in such an energy flash of time, that it allowed little time for the group to take stock and formulate the proper development of Wire. They essentially took a break for five years or so, with solo projects being embarked on, Newman in particular releasing three albums between 1980-82.

As a decade, it was a strange and challenging time for the group.

“In the ’70s, we were kind of the cool kids,” Newman says, looking back. “We were getting extraordinary reviews, we were the band that was always looking forwards. It was then a bit confusing in the ’80s – people caught up with us but then we were engaged in a different mode, which was adventurous of us but not always successful.”

A lack of communication in the group led to some struggles, too, and Newman says: “We never talked about anything ever, in that blokey kind of way, and so many things went unsaid and that kind of spilled over into the ’80s. There was no means to discuss or decide anything as a band, which makes it very difficult for a set of individuals to do anything together.”

When they did reconvene, they did so in typical Wire fashion and ostensibly attempted to blunder the past to death. “When we came back we were quite sure that we weren’t going to sound like we did in the ’70s.

“In the mid ’80s there was nothing more out than punk rock, to be honest. Hardcore was happening in America but that wasn’t relevant to the UK at all. What was happening in the UK was basically machine music. We got in a room and Bruce said we should regard it as year zero, to rewrite everything from the ground up.”

The first full Wire album in the 1980s was 1987’s ‘The Ideal Copy’; a record rooted more in synthesisers, samplers and a glossy, more dance-like production. Whilst scattered with moments of brilliance, it felt like a group trying to settle back into themselves and perhaps not quite finding their own groove quite as quickly and easily. “We got there in the end but it took us a couple of years,” Newman reflects. “It felt strange as well, because in your twenties you have this insane confidence, like you rule your own world, but you don’t actually even rule your own sandwich. That starts to dissipate as you get into your thirties. You feel more vulnerable, and less like you have any control over how anything works.”

Towards the end of the ’80s Wire drummer Gotobed left the band and they dropped the ‘e’ from their name, temporarily becoming Wir. Soon, in 1991, the group went on an extended hiatus and it wouldn’t be until 2003 that the band would release another album – ‘Send’.

When Wire reunited with Gotobed back in the band they soon had a temporary setback with original member Bruce Gilbert leaving. They continued as a three-piece for a while before Margaret Fiedler McGinnis temporarily filled a gap. Then It Hugs Back’s Matthew Simms grew from a touring member to a full time one in 2010.

By 2011 the group had released ‘Red Barked Tree’, which was as strong an album as they had made in decades. The group sounding solidified, re-energised and locked into a sound that was coated in shimmering yet vicious guitars. Newman’s treated vocals also succeeded to sound both biting and glossy, with a general urgency and melodic intuition that has now set the tone for the last six years, in which the group have released consistently excellent material. The latest is the genuinely brilliant ‘Silver/Lead’.

Important factors in the band’s on-going success have been their own label (also called Pink Flag) and the way in which Wire now approach things with a more carved-out plan.

“It’s a weird thing, nothing succeeds like success,” Newman says of what keeps him going. “I think a lot of artists can be very passive and it used to be this system of having to create demos to impress a man who has money and they give you that money as long as you keep doing whatever it is you’re supposed to do, and then when you don’t fit the bill any more you’re out. That can be quite destroying. Or being on indie labels and just making enough with each new release to get by and pay rent and make another record but never really owning something. But since 2000 we own absolutely everything we have made and we can continue to exploit it in whatever way we want to.

“We didn’t really start to see anything for our efforts until the last decade. It isn’t all about money, but there’s something about the effectiveness of what you do – it drives you to do more things. If we’d have just gone back to Mute I don’t think it would have lasted more than a couple of years. We’d have put out the record, it would have done pretty well and Bruce would have still been on the dole.”

This autonomous machine that is Wire, the ever-forward looking band, the business, the label, the festival curators (their now annual DRILL series of events), is functioning at maximum efficiency and this leads to creative successes, too. Getting there, though, isn’t always harmonious. Underlying frictions still reside in the band, and after 40 years together as people it’s clear they aren’t going anywhere. Of the band’s dynamic, Newman says: “I don’t think we’ve ever regarded ourselves as friends, which is a pity in a way. It’s more of a dysfunctional family. The main interest in the band has always been looking forwards, that’s the only thing we have in common to be quite honest.”

He says the band are more effective communicators these days, although it’s not always an easy process. “We’re not sitting there stroking our chins saying, ‘hmmm, let’s do this,’” he says. “It is incredibly lively and with a lot of opinions going in different directions, with four incredibly different people with strong and different ideas about how things can be.” And whilst this friction leads to unquestionably interesting results, it’s not always in the manner than people presume it to be, according to Newman. “People used to think that the conflict was the source of the creativity. This is not true. The conflict is a product of the creativity.”

Perhaps the most interesting thing about Wire 40 years in is not their frequently celebrated past glories but the fact that they are still a contemporary band in 2017. “There is a fundamental split in the industry of heritage acts and older artists, and contemporary artists, people in their 30s and younger. It’s very hard for someone to be contemporary and older,” Newman says. “It’s gotten easier now but 10 years ago it was an uphill struggle to get people – even if they liked what we were doing – to take us seriously as a contemporary band. I think it’s purely desire to just bloody well do it and get on with it.”

On this point, part of the battle has come from the group’s refusal to entertain the idea of doing the nostalgia circuit.

“I think Wire is still the most famous group you’ve never heard of,” Newman says with a slight laugh. “There’s still a massive untapped world out there. I mean, here’s a test – look at all the announcements for all the festivals this year, it’s Wire’s 40th anniversary and how many are we on? There’s still a glass ceiling; a point beyond which we can’t go because we don’t play the heritage game.” Which of course leaves a parting discussion on the only thing Wire are ever concerned with: the future.

Wire at 40 sees a new album and curated festivals dotted across the globe, so what will Wire at 50 look like? In a manner fitting entirely of the same group that took to the stage at the Roxy in 1977 without a conventional care in the world, Newman says: “When it comes to the 50th we might just be obstinate and just not celebrate it.”

Photographs by Malka Spigel and Annette Green