Though vivid, descriptions are often brief, with anecdotal snippets liberally applied to form the album’s patchwork narrative. “Songwriting isn’t about being accurate. It’s a sort of energy you nick from things and turn into something that everyone can interpret for their own benefit. You don’t want it to be a documentary-led piece of information. Music that gets burdened by detail eventually becomes shit.” Baxter doesn’t tend to mince his words. His meandering storytelling forms cockney hieroglyphics, a line like “lick my forehead you whitebread-eating cockroach” being one of the album’s most ‘colourful’. “They’re just artefacts in the back of your mind. I don’t censor them. In a way, it’s quite lazy because I allow them to be printed. But if you think about it too much you prevent a sentence from happening. It’s quite a pretentious Beat poetry flow. You have to open it up, in a sort of buddhist way, to let them go.”

Ambiguity seems to suit Baxter, who prefers to remain tight-lipped on the gory details of his days as a troublemaker. Rather than indulge in anything too incriminating, his attention is focused on the revolving door of characters who are introduced and reappear across the tracklist.

“He was quite an unpleasant, dominating kid. But I’d come from the countryside so I was probably a bit vulnerable,” he says, scrunching his nose and discussing a foiled heist carried out by him and his toxic schoolmate ‘Leon’ to steal a pair of sunglasses. “We got into a lot of mischief together but he always held the power. He was a bit Rasputin-esque. It took me ages to realise that I didn’t have to take these people too seriously. Although I made efforts to stop him from taking advantage of me, it’s better sometimes to stick with the dictator you know.” The story, which wound up with Baxter taking the heat and getting busted by the police, didn’t get a mention in the book. Maybe for good reason. “Usually when I talk about these people I have to tediously disguise their identities by changing everyone’s names. But legally speaking, songwriting is different because it’s not viewed as a very accurate account of something. It must be slightly litigious, especially when I’m telling you now that he was a total cunt.” Sorry Leon.

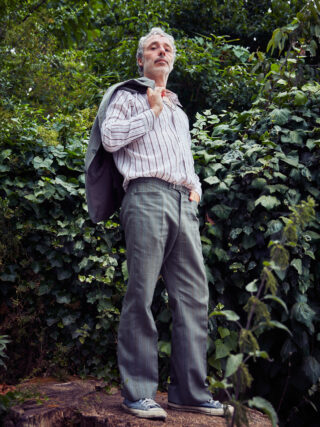

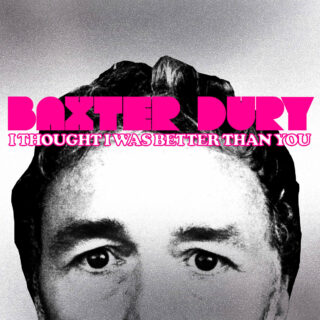

When he’s not being reacquainted with names and faces of his past, Baxter Dury isn’t just reliving his childhood, he’s reckoning with it. Behind the tough sunken-eyed exterior lives a sensitive artist who has borne the weight of his father’s life’s work – a burden he hopes to finally lay to rest on I Thought I Was Better Than You. You’d be wrong to assume there is an insurmountable expectation of punk royalty for Baxter to live up to; so much of what he does feels like an exception to the rules he may or may not have inherited. Rather than Doc Martens and pub-punk, Baxter grew up a hip hop head and is currently more interested in an artist like Frank Ocean, who he namechecks on the record, than the direct legacies of his father’s generation.

“I think it’s very refreshing, inventive music,” he says, pondering the evolving elements that moves hip-hop from one generation to the next. “In a way, it’s gone back and forth. English appropriation of American soul music was originally what made us [British musicians] interesting. And then it sprung back the other way in the ’60s and ’70s. You can hear an English influence in artists like Frank [Ocean] and Tyler [The Creator] that goes right back to The Beatles.”

This intergenerational crossroads feels like a well-trodden path for Baxter. His new music uses looser hip hop inflections to transform his own weathered Southern English drawl, a combination which helps I Thought I Was Better Than You assume its unique identity. Rather than conform to an idea of what people might expect or want him to be, it’s a body of work that feels closer to Baxter than ever before. “It all becomes a real cultural mosaic of everything. That’s really interesting, but it’s not exactly hip hop anymore.”

Perhaps it’s no surprise that he resonates with the modern West Coast superstars that refuse to wear a label, with Baxter’s own experience entirely stuck on the peripheries of what others accept to be normal. “They’re just leaders in something more inventive,” he continues. “It’s kind of punk and fucked up as well as being dangerous in subject matter. I guess if you’re a Black American, you’re sociologically sponsored by a much bigger picture than provincial islanders. There’s something very deep and really incomparable. It’s got a lot of what we like about everything, but it’s actually new. I don’t really see that happening anywhere else.”