Black Midi and the Holy Grail

We sent London's weirdest rock band to a Da Vinci-themed escape room for no good reason

We sent London's weirdest rock band to a Da Vinci-themed escape room for no good reason

When I was told I was going to interview London experimental rock group Black Midi in an escape room in Shepherd’s Bush, I’d be lying if I said that the Vice-meets-Partridge character of the prospect didn’t occur to me. But considering that the previous idea had been ‘Wild Swimming with Black Midi’, and myself and at least one member of the band are barely able to swim, it seemed the better option. Although I maintain that ‘Drowning with Black Midi’ does have a ring to it.

Regardless, the LARP-y thrills of an escape room perfectly fit the band’s off-kilter approach, and upon being locked in the small room with bassist Cameron Picton, vocalist/guitarist Geordie Greep and drummer Morgan Simpson, the mission is taken head-on and in good humour. The infectious enthusiasm of our Games Master (aka, the guy working at the escape room that day) is also notable; he’s bemused yet intrigued by the proposal of an interview taking place in one of his rooms.

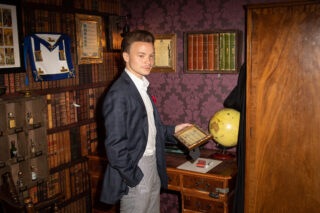

The ‘Da Vinci Room’ itself is decked out like an office with eerie, cultish inflections. Robes adorned the walls alongside replica academia and certification. A typewriter sits on the desk. A wardrobe looms large. The task at hand is to find the Holy Grail, and along the way, find out a little about the group’s new record, Hellfire. There are codes to be cracked, and questions to be answered.

Hellfire, the group’s third outing, expands on the oddball quirks and unashamedly accomplished musicianship that has long set the group apart from a U.K. music scene that’s increasingly resembling some sort of backwards-looking, post-punk revivalist wasteland. Where some contemporaries may be guilty of a lack of imagination, satisfied to cash in on the rehash industry, Black Midi continue to persevere with a blinkered drive, beguiling and alienating in equal measure.

The new record is a collection of tall tales about low-lifes, soundtracked by an anything-goes approach that, more often than not, veers on sheer musical theatre at its most nauseatingly accelerated. Though not narratively coherent by design, the tracks certainly feel that they inhabit a world, with a first-person perspective that vividly narrates its revolving rogues gallery. I’ve sat with the record for a week or so before entering the escape room, and truth be told, I’m still not entirely sure what to make of it.

As we begin searching the office for clues, I question lead vocalist Geordie on his notable shift in writing style, which sees him embodying characters rather than observing them.

“A lot of the last album was third-person because at the time I felt it was an easier method, it felt like it could be much more stylised. Writing in first-person, there’s more potential for scrutiny of the veracity of it, it feels like it needs to be more true to life. Now I feel more comfortable playing with it.

“I was always hesitant to be upfront with what the songs were about, to make their meaning too evident,” he continues. “But then, when something is more abstract, you realise you can’t underestimate the audience’s ability to come up with the naffest meaning possible, something you absolutely didn’t intend. So I just thought, ‘Enough of that, I’m gonna make it extremely clear what it’s about.’”

With this shift has come a more pronounced fleshing-out of characters, making ample use of Greep’s signature animated vocal style. His approach on the opening title track brings to mind Tom Waits at his most rousingly sodden, a good fit for the sleazy disposition of the many denizens of the record.

“I do like Tom Waits,” he acknowledges, “but really the first track is almost a direct rip-off of [authors and playwrights] Thomas Bernhard or Samuel Beckett, as well as Richard Yates. People like that.”

As the album takes its deep plunge into the theatrical, more surprising influences rear their heads. I suggest that there’s a strong element of Frank Sinatra to tracks like ‘The Defence’, with its grand, stirring tension and release. Greep nods, adding, “For sure, stylistically it sounds like that, but the subject matter is not something you’d typically hear in one of those songs. I really like the short stories of Guy de Maupassant – ‘The Defence’ is inspired by one of them. ‘Dangerous Liaisons’ is really inspired by the short stories of Isaac Bashevis Singer, a Jewish writer, who did all this work about people being possessed by the devil, making deals with the devil, or women having affairs with the devil, but with good humour. But also that track owes a great debt to gangster movies, hitmen, true crime, all that.”

Mentions of the literary and filmic influences seem to provoke a more keen and concise response from the singer, but he goes on to acknowledge a variety of musical touchpoints that contextualise the sonic direction of the record, while explaining the inherent juxtaposition of the lyrics and music as the driving force.

“The cabaret songs of Kurt Weill from the 1920 and ’30s, loads of musicals, Rodgers and Hammerstein. Singin’ In The Rain, and all that,” he says. “I also love Barbara Streisand. But it’s taking all that stuff, and giving it dark humour, a sense of the macabre. What they wouldn’t usually be talking about in that kind of music.”

Elsewhere on Hellfire, Greep’s love of boxing is a clear inspiration for ‘Sugar/Tzu’, a track that stems from one of the group’s earliest jams as school children. While Geordie and Cameron attempted to crack a reverse riddle using a mirror, I ask Morgan about the track.

“That’s probably six or seven years old,” he reveals. “Me and Geordie used to just jam, and it’s one of those bits that’s always stuck with me. We’d probably tried to shoehorn it in before, but this time it just felt right.”

He goes on to explain how the album’s recording continued to develop the band’s focus on traditional songwriting, rather than the jamming that had characterised much of their earliest work. “It’s definitely a continuation of the second album compositionally. We realised the success we had working in that way. Also, time-wise, it’s less excessive.”

I ask if the group have moved on from explorative jamming as it has outlasted its purpose of allowing them to understand each other musically; now they are so used to one another, they can afford to be more direct. Morgan responds, “Yeah, maybe. I’ve never thought about it that way. The jamming felt like the only thing we knew at the time, not that we did it to understand each other musically, that’s just what was going on then.”

“It was an intense recording process,” adds Cameron. “Besides two tracks we did in June, the rest were recorded in 13 straight days, and we were the only ones constantly in the studio.” That last sentence suggests a certain confidence; three albums in, that seems to be the prevailing theme.

“Essentially, it’s just being less afraid of doing something because it’s too ‘naff’, or not coherent with the general sound,” asserts Geordie. “Just being more open to doing stuff that we actually like. A lot of the music that I like has that campy sense, and that kind of fearlessness in putting disparate sounds together. So, it’s just being more open with that, and working with, not necessarily pastiche, but incorporating unlikely things in an interesting way.”

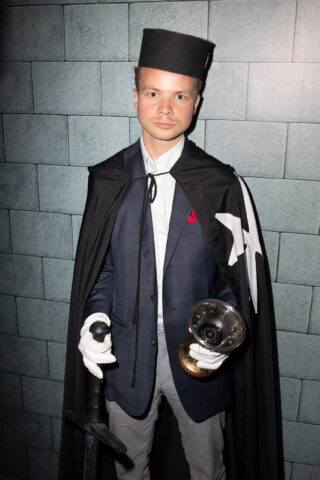

The group have now robed up in the Knights Templar-style garments that were in the room when we entered, and which hold further clues when examined using U.V. torches. “For me personally,” Morgan says, “it’s a meeting of the first and second album. We’ve brought back the claustrophobic energy of Schlagenheim in a way that we didn’t with Cavalcade.” There’s certainly a claustrophobia to the density of the record, but overall there’s an expansive theatricality to the album. Both sonically and compositionally, it drips with big band bluster, asserting itself with knee-jerk stage-show tonal shifts and vocal spotlights, allowing Greep’s characters to grapple the pace of the record to their individual needs.

“The lyrics were done in a very short period of time,” he explains, “I just kept coming back to the same stuff. At first, I thought it was a bit cheap to be harping on the same subjects so much, but it was just what was naturally coming out and it made sense together.”

For all this, it certainly still sounds like Black Midi, but with a bigger hat on. And maybe a cane, waved intermittently with expressive bravado, helping to pull the whole thing along. It’s difficult to explain, not least for the band themselves; yet when I ask if this was intentional, Morgan straightforwardly replies: “100%.”

“Even live,” Cameron adds, “the performance itself is very theatrical, lots of coordinated dancing, lots of stupidness, for lack of a better word. Not that different from a cabaret show.” This doesn’t feel like an artistic shift, rather an expansion of the camp showmanship that has cast the group as anomalies in whatever scene people seem to have placed them in.

I ask Black Midi if they ever worry about alienating their fanbase with their seemingly nonchalant approach to stylistic left-turns.

“I think we’re actually trying to grow that,” Cameron retorts, “When we go to the U.S., there’s no expectation from the crowd as to what we do, they’re just happy to see what it is.”

I’m taken aback by the unanimous verdict on the difference between U.K. and U.S. audiences that follows from all three band members. “In the U.K. and Europe there’s much more of a specific type of performance that you are expected to put on, or certain songs you are expected to play, or play in a certain way, or whatever,” Cameron expands.

Could this simply be the predictable fallout of the level of hype the band saw initially in the U.K.? Geordie counterposes that “it’s ‘cos the audiences here are a bit entitled, with the legacy of British music, the attitude is a bit like ‘you’re lucky you’ve even got a show, you’re lucky we are even coming to your show’, where as in the U.S., you’re just a foreign band coming over, they are just happy to see some music. It’s the same in Eastern Europe, Russia, Japan. They are just happy to see a show.”

Interestingly, it’s almost a cliché of American alternative artists from previous generations to say the reverse, comparing a lack of reception at home to adulation in Europe. “Maybe it’s just a grass-always-greener thing,” answers Geordie.

At this moment, the combination lock on the wardrobe is cracked, and a rush of genuine exhilaration washes over us as a secret second room is revealed. As we continue onward, I return back to the group’s earlier years. Much has been said of Morgan’s childhood playing in family church bands, or the band’s formation at the infamous BRIT School, but I wonder what music it was that they first felt they’d discovered on their own.

“Frank Zappa,” says Geordie. “My dad wasn’t a huge fan of Frank Zappa, but I got really into him. All of the bands I got into when I was younger, like AC/DC, was stuff he wasn’t really into.”

Morgan zeroes in on a later influence. “I think for me, it was when [D’Angelo’s] Black Messiah came out, that was a game-changer. That was the first record where I was just in that world for months. It’s always cool when you have a point when you realise you can have your own taste. You realise you don’t have to listen to what your parents or mates are telling me to listen to.

“The thing I love about D’Angelo is that he’s not afraid to pay homage to his forepeople,” he expands. “Be it James Brown, Funkadelic, Sly and the Family Stone.” The idea of paying homage rings true for the group, who are known for their at-times-unexpected covers (Taylor Swift’s ‘Love Story’ a recent example). While there’s certainly an element of humour to some of these renditions, it would be foolish to ignore that they’re still driven at heart by the band’s sheer enthusiasm for music. “It’s just songs we really like, like ‘let’s just do it’, just playing homage,” says Morgan. “Songbook vibes. The Black Midi songbook, coming soon…”

With that, the timer goes off. Our hour is up. We didn’t find the Holy Grail. We didn’t escape. “Now we’re not gonna get on the Wall of Fame,” I hear a slightly dejected voice mutter.

“When the secret door opened though, that was an epic moment,” says Geordie with a genuine smile.

Later that night, Black Midi announce an impromptu gig at the Lexington in Islington. The group made clear earlier that they see the live and recorded components of what they do as two different entities, and as they came on to the stage, many of the things we had spoken about came to mind. Opening fan favourite ‘953’ is prefaced with a sixth form-like interpolation of Metallica’s ‘Enter Sandman’. Joined by a keyboardist and a saxophonist, the newer tracks meld seamlessly into the setlist, a cacophonous barrage, where songs rarely seemed to begin or end in any coherent manner.

It’s now clear that my question about alienating the audience was a non-starter, as the crowd is hysterically engaged throughout. What strikes me most is the myriad of literary influences that Geordie mentioned earlier. For all the frenetic energy that the tracks gain from the live performance, the storytelling is understandably cut adrift in the wall of sound. I feel a latent appreciation for Hellfire, eager to return to its nightmarish showtunes after having experienced its full extension of on and off-stage mutations.